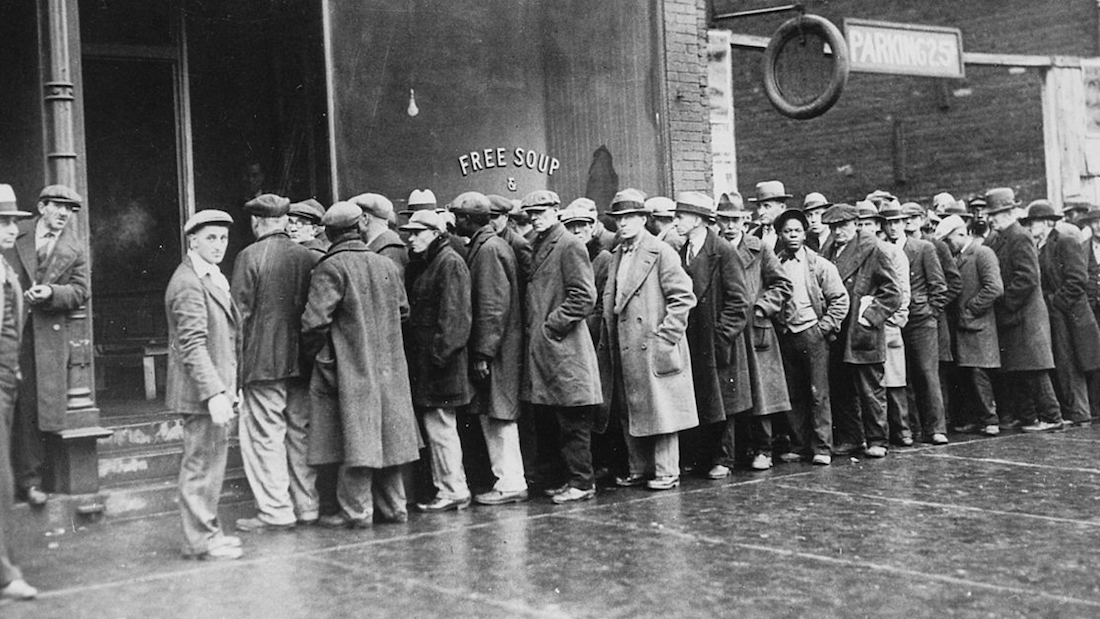

The Twentieth Century should have taught the World a lesson. Fascism, whether of the Nazi stripe in Germany or other varieties such as that of Italy, failed miserably. Socialism, especially of the communist variety, ran a dead heat with Fascism for the most miserable failures. Given the hackneyed behavior currently being manifested by Vladdy Putin, who seems to strive to be part Josef Stalin and part Peter the Great, is pursuing a path taken by Adolph Hitler just preceding WWII. Georgia and the Crimea have replaced Austria and the Sudetenland, but the new bully on the street is just warming up. Déjà vu!

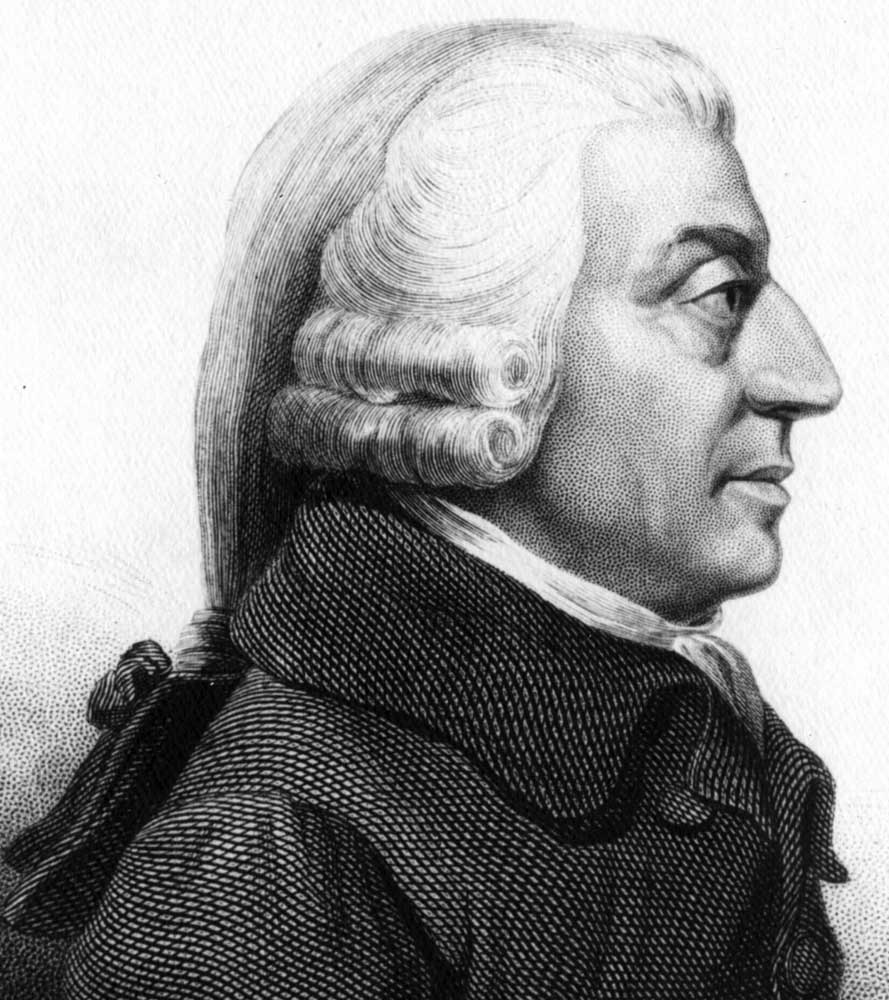

Why the kudos for free market capitalism? That praise only fits if it is of the competitive variety and not a first cousin to fascism owing to a lack of sufficient competition; or the Invisible Hand, as Adam Smith called it in his Wealth of Nations. The end game or limiting case for competitive free market capitalism is the achievement of the theoretical economic welfare conditions of efficiency and equity on the microeconomic level, and high employment (or the natural rate of employment) and a reasonable degree of price level stability on the macroeconomic level. To fully achieve these goals or conditions of theoretical welfare economics, perfect competition must prevail in all markets, both the product markets for goods and services and the productive resource markets for labor, debt and equity capital, entrepreneurship and land.

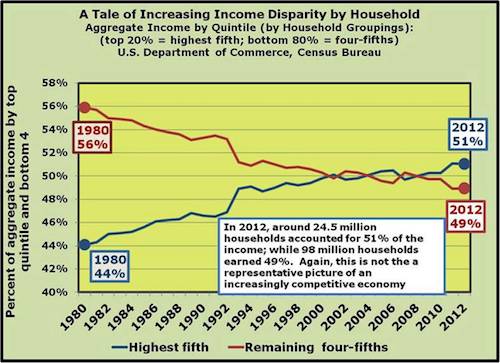

Of course these end game conditions of all markets being perfectly competitive and in long-term equilibrium never exist so we have to think in terms of a spectrum with the ‘ideal’ economic setting at one end and at the opposite end, markets that are monopolistic on the sellers’ side and/or monopsonistic on the buyers’ side. The effects of this latter case, or end game that also never exists, where monopoly power dominates would be a gravely excessively unequal income distribution that benefits the top decile or quintile or so of that income distribution and leaving the rest far worse off than if significant competition was otherwise present in all of the markets. This latter case where monopoly or monopsony power dominates the markets, would reflect a politically unacceptable degree of income inequality and a grievous degree of failure to achieve the goal of equity as compared to the former case where vigorous competition in all markets prevails.

Elsewhere, we have pointed out that a sizeable portion of the economy falls short of the ideal or limiting case of vigorous competition. Given the size of the market and technologies available, cost structures cause some markets to fall into the category of natural monopolies and others, natural oligopolies. In some markets, there is the presence of externalities: cost external to the firm and benefits – not directly reflected in gains to the buyers, but present to society as a whole. Some markets are unable to exclude the non-payers who become what are termed ‘free-riders’, those refusing to fully reveal their preferences but nonetheless enjoying the benefits from the production of the good or service. To the extent that such conditions exist, the economy operates more distantly from the limiting case that results in the full achievement of the theoretical economic welfare conditions. In an optimal sense, some markets overproduce and some under-produce, thus lowering the material standard of living, violating the welfare conditions of efficiency as well as equity. In reality, these markets can change from more – to less competition and likewise from less – to more competition. The beer brewing industry is one such example and the production stage of electric power is another such example. In years past, the former led to less competition and the latter to more competition. Many other examples abound on the dynamic landscape of market structures, both in the markets for goods and services and for productive resources such as labor and capital.

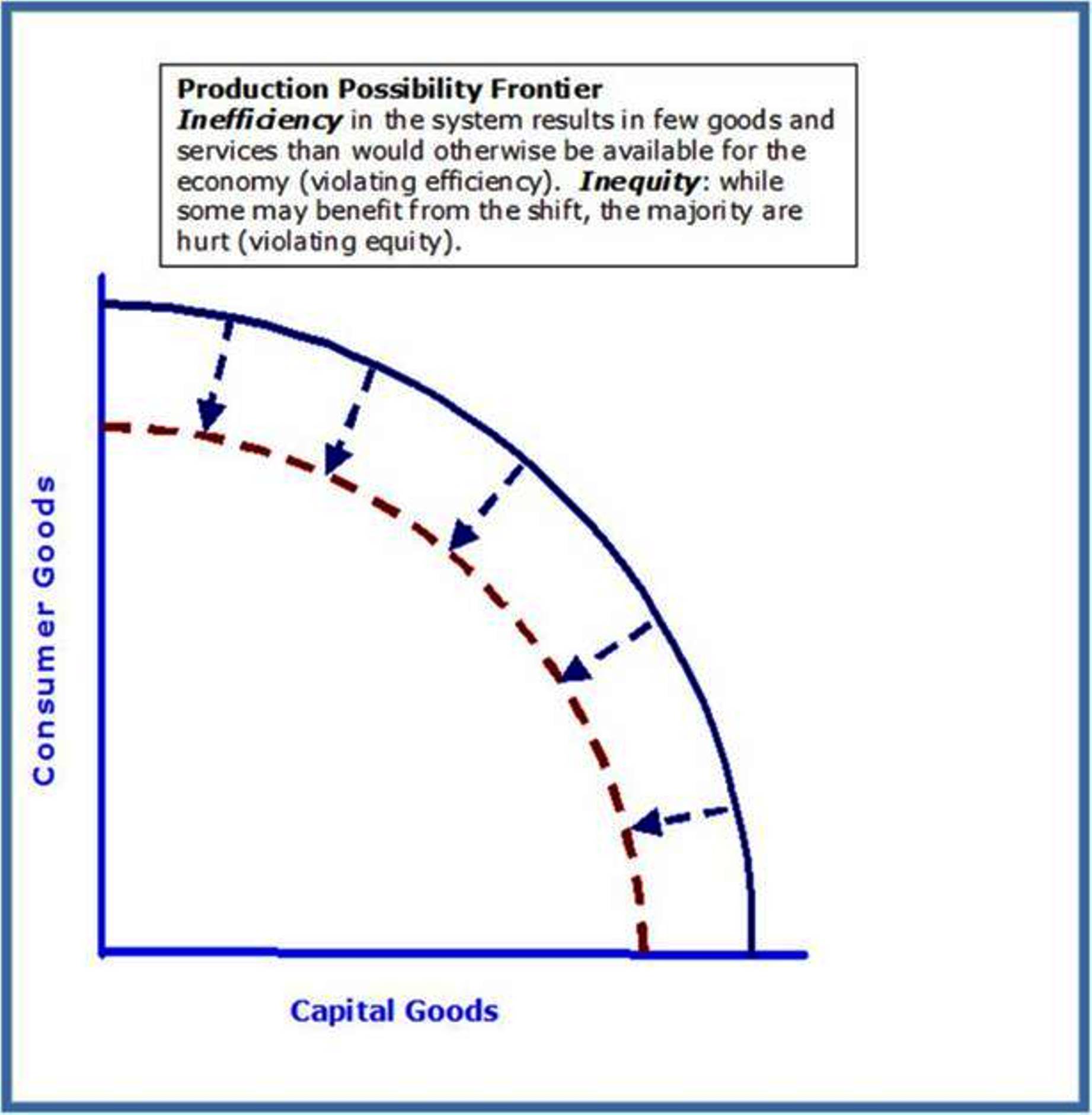

To sum up, the lack of significant competition in markets results in a significant reduction in the per capita (individual) level of income and production, that is a failure to achieve the microeconomic welfare condition of efficiency. As a result, our economy falls far short of the material standard of living that could be achievable given our stock of productive resources and the currently available level of technology. The economy would be operating within its production possibility frontier.

The way to minimize the problems in markets characterized as natural monopolies and oligopolies is to vigilantly enforce the anti- trust legislation to minimize as far as possible the wielding of monopoly power by suppliers in both product markets such as crude oil and productive resource markets such as for labor, capital and entrepreneurship. The effective enforcement of anti-trust laws is not anti-capitalistic but is necessary to bring economic activity closer to the full achievement for its citizens of the potential welfare a capitalistic economic system is capable of delivering. We can see the failure of free market capitalism to achieve equity and efficiency in the highly cartelized markets for crude oil and its refined downstream derivative products such as gasoline. We can see the movement toward equity and efficiency as fracking restores some of the lost competition in the market for crude oil and especially for natural gas thanks to the growing importance of shale fields such as Marcellus, Eagle Ford and Bakken. Big oil such as OPEC and its fellow travelers in the re-cartelized American segment of the oil industry are already crying as the recent comment by a Saudi Arabian Prince proclaims (CNS News, January 6, 2014).

According to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), fracking (and horizontal drilling) has resulted in the United States becoming (in 2010) the world’s largest natural gas producer. Also, in October 2013, domestic oil production surpassed the amount of oil imported into the United States for the first time since 1995.

The chorus of environmentalists, especially of the non-scientific stripe, supports the wailing of the Big Oil banditos as they fear the loss of control of the supply in these markets will result in a loss of a considerable portion of their huge surplus profits. In a more narrow sense, the owners of railroads fight pipelines and the loss of the very profitable transport of petroleum products to refineries and retail markets over the existing railroad networks. You can fill in the blanks and connect the dots without much difficulty! Greed and ignorance is a dangerous tandem to any well- functioning economy and as a result the loss of economic welfare of its citizens.

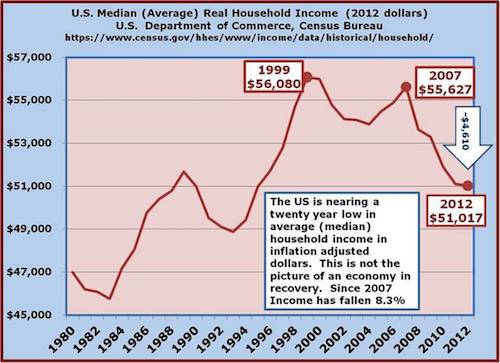

We can also see the failure to achieve high employment as Employment Reports over the past few years have shown clearly. The decline of competition introduces downward price rigidity in such markets and causes a twin bias toward intermittent periods of recessions and episodes of unacceptable high inflation rates.

Labor unions can have the same effect as do business cartels. By reducing supply and through collective bargaining, they can achieve an above equilibrium labor compensation rates for its members. In the long-run this triggers the substitution affect as more capital intensive technologies replace labor intensive technologies. Accelerated automation can be clearly seen in modern factories and seaports.

No doubt the passage of a definitely not so affordable, Affordable Health Act, referred to as Obamacare, has added to the economic malaise facing our nation. Uncertainty undermines the ability to make rational choices. It is an awkward and excessively costly attempt at addressing excessive inequality in the income distribution of the U.S. of A. It is to a clarification of this issue of income inequality that our analysis now turns.

Ask some questions to the critics of the American economy who continually demand a lessening of the inequality in the income distribution. What constitutes excessive inequality and what are its causes? What should be the tax rate structure to address the problem of excessive income inequality? Much of the time you will hear some incoherent mumbling at best and silence at worst.

There certainly is an excessively unequal income distribution as many oligarchs agree all the way to the banks to invest their huge and excessive reward as productive resources. While not exactly oligarchs, members of some labor unions are included in this group. The rise of the phenomenon called ‘sticker shock’ is a result of the few wielding monopoly power over the many.

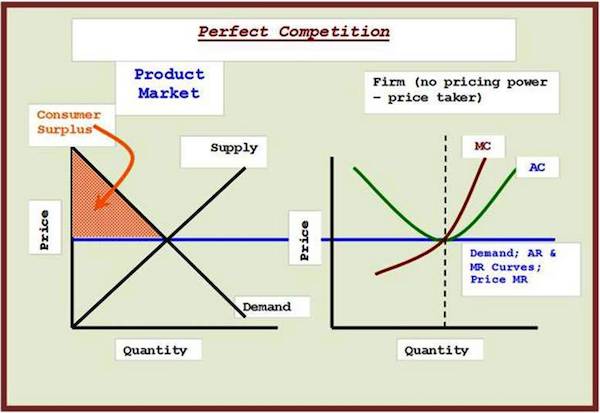

Let us begin our analysis by first examining the economic welfare condition of equity. As we shall see, equity is not equality. In fact, complete equality would be inequitable! The limiting case of perfectly competitive product and productive resource markets in long- term equilibrium would bring about equity.

In perfectly competitive markets in long-term equilibrium, the productive resources laborers, debt and equity capitalists, entrepreneurs, and owners of land (which consists of natural resources and earthly space), receive their opportunity costs. They would receive just what it takes as a reward or income to bid them away from their next best competitive employment, no more and no less. There would be no economic rent paid them. Economic rent or its modern vernacular equivalent, producer surplus, is the measure of a productive resource’s reward in excess of its opportunity cost and the cause of an excessively unequal income distribution that dominates the political debate today.

When markets are perfectly competitive and in long-term equilibrium, the result is that the buyer pay the lowest price possible consistent with the need to reward all productive resources engaged in the production of the good or service in question, their opportunity cost, no more and no less. The result is that the consumer surplus is maximized.

What is the consumer surplus?

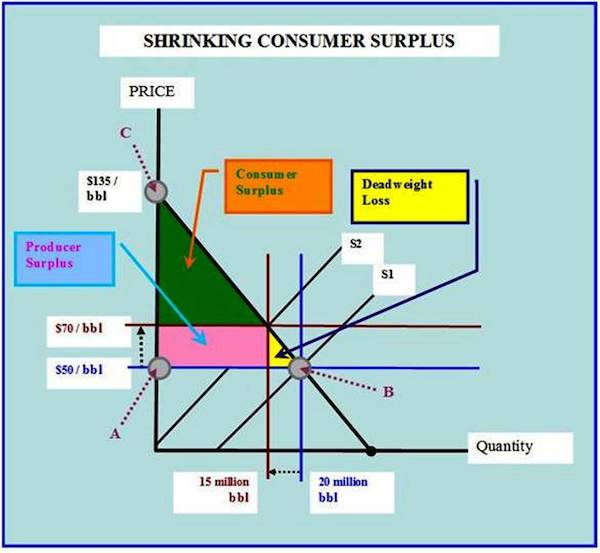

If you study this graph, explaining what a cartel such as OPEC does in order to increase the price, you will notice several things. First, note the triangle (for straight line demand curves) with its base as the perpendicular line from the price axis (Segment AB). Next, the line segment of the demand curve from where it meets the supply curve up to the price axis (segment BC). Lastly, we have the price axis down to the equilibrium price (segment CA). This is what is referred to as consumer surplus when the price is $50 per barrel. The buyers or consumers in this case, expend an amount equal to price of $50 per barrel times quantity demanded of 20 million barrels or $1,000,000,000 or 1 billion dollars. This is also the total revenue going to the firm. This revenue will then be used to pay all expenses with the remaining revenue being called profit, in an accounting sense. The triangle we have called the consumer surplus represents an estimate of additional expenditures the consumers would have paid if they had to in order to acquire the equilibrium quantity of 20 million barrels. In our example, the original consumer surplus is one half of [$135 -$50] or $85 times 20 million barrels or $1.7 billion.

Some of the potential revenue represented by the consumer surplus could be expropriated by the firm using a technique called price discrimination. A simpler tactic would be reducing the supply and driving up the price to everyone. If the firm is not able to do so, the consumer surplus stays with the consumers. Note: in this example, OPEC raised the price from $50/barrel for crude oil to $70/barrel of crude oil by reducing the supply from supply 1 to supply 2. The consumer surplus would shrink significantly – the consumer would pay more, receive less. The loss of the consumer surplus is equal to the increase in the producer surplus of [$70-$50] or $20 times 15 million barrels or $300 million plus the dead weight loss of one-half of ($20 times 5 million barrels) or $50 million. The total loss of consumer surplus would equal the sum of the two or $350 million. There are further implications of deadweight loss, (deadweight loss: neither the consumer, nor the producer receives this portion of the former consumer surplus; the result is loss of surplus value). Should we desire to see the effect of increased competition, assume a major new oil field came into production thus increasing the supply of oil from supply 2 to supply 1.

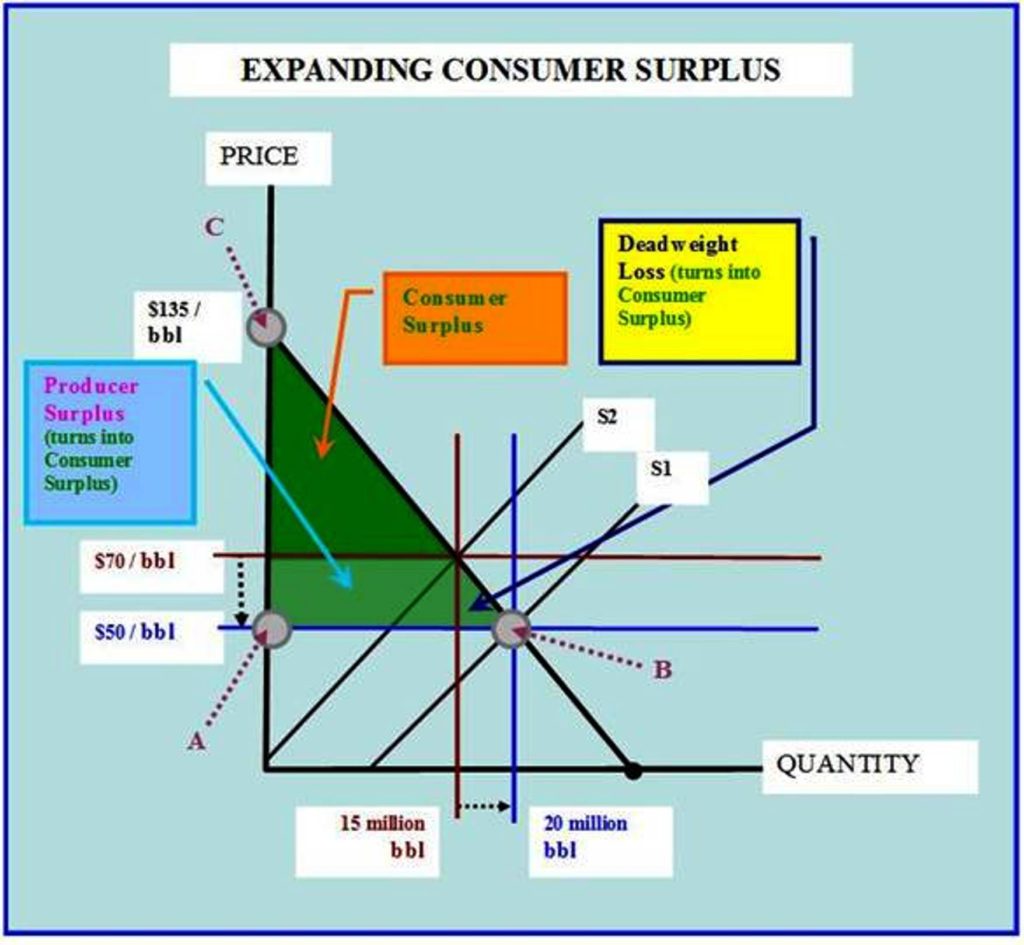

Now reverse the direction of the changes. The producer surplus would decrease and the deadweight loss in this case would go to zero. The consumer surplus would increase by the sum of the decrease in the producer surplus plus the decrease in the dead weight loss.

This has income distribution implications. Everyone is a consumer! Not everyone is a productive resource nor does each of the productive resources possess the same quality and quantity of resources. To the extent the economic rent or surplus rewards (in excess of opportunity costs*) is shifted to the consumer surplus by an increase in competitive pressures in the market, the income distribution of individuals and households will be less unequal than it would have been had the productive resources retained the surplus. Thus the increase in competition resulted in a greater conformity to the condition of equity and as we argue, greater conformity to commutative justice.

This is the compensation that a productive resource (e.g., labor is both the resource and the individual) could earn in its next best COMPETITIVE alternative employment. Remember that the productive resources include not only labor, but debt and equity capital, entrepreneurship and natural resources and space – the latter is usually referred to as land. Included in opportunity cost is what is referred to as ‘normal’ profits; again, this refers to the resource just receiving enough compensation to keep it from moving to its next best competitive alternative.

Since everyone is a consumer while only some of society supplies productive resources, as markets become more competitive, the consumer surplus increases relative to the producer surplus thus reducing the excessive inequality in the income distribution. On the other hand, as competition in markets decreases, the producer surplus increases (economic rent or excess reward to productive resources increases) relative to the consumer surplus and this increase the excessive inequality in the income distribution.

Competitive markets do this without the need for income redistribution policies that history has shown can damage the average citizen’s standard of living and slow the rate of economic growth of the economy as a whole.

Those on the far left are to some extent ideologically blinded to the producer surplus or economic rent going to labor as labor markets some of which have been cartelized by unionization and some of the non-essential aspects of credentialism.

Those on the far right are to some extent ideologically blinded to the surplus rewards or producer surplus (economic rent) going to entrepreneurs and equity capitalists due to the lack of sufficient competition.

Increasing competition in all markets, move the income distribution toward the achievement of the theoretical economic welfare condition of equity while declining competition in markets increases excessive income inequality and moves the economy further away from the achievement of the economic welfare condition of equity.

In the field of social ethics, increasing competition brings the economy closer to the achievement of subsidiarity and the movement toward equity promotes solidarity among the members of society.

The greater the degree of competition in the markets of an economy, the less is the need for income redistribution policies. Since such economic policies are incapable of defining clearly the equitable income distribution and tax and transfer of income pursuant to that determination, such policies are fraught with danger to the other economic welfare goals of efficiency, high employment, and a reasonable degree of price level stability.

This helps to explain the economic malaise around the World including the U.S. of A. Several consecutive years of relatively slow economic growth give clear evidence of this dilemma.

Just as failing to achieve efficiency causes the economy to operate within its production possibility frontier or curve, so does excessive unemployment, or operating at a level of production that is less than that which is commensurate with the natural level of employment. The cause of this shortfall in respect to the natural rate of employment is due to the labor market not being able to be truly cleared due to the lack of sufficient competition.