I have to chuckle every time my fellow Catholics pray for world peace. It reminds me of an irreverent bumper sticker I saw years ago that encouraged us to pray for whirled peas. While praying for universal peace is a noble gesture, the thought of actually achieving real world peace on this deeply flawed earth is a fruitless exercise in self-delusion.

Peace on earth will never be possible because of what philosopher Emanuel Kant called the crooked timber of humanity. Wars, violence and other human evils are a regrettable but undeniable part of the human condition. Like the poor, wars will always be with us. To pretend that we can eliminate them is foolhardy and a sign of the materialistic disease of the spirit that has infected our culture.

Fantasies are fine for football leagues or poetry recitals but in the real world, utopian goals can only serve to distract us from our eternal destiny. In chasing such windmills of the heart as peace on earth, many of us have lost our moral equilibrium.

On the way to Sunday Mass, I often remark about how religious all the runners, bikers and other exercise fanatics are with their physical regimens. They are out there every Sunday and on many weekdays in all kinds of hot and inclement weather. What dedication they show for maintaining their sleek bodies. I can’t help wondering if they pay as much attention to their souls.

Our country is a sick society—morally sick amid a cornucopia of boredom, violence and material excess. We are restless and unhappy with the state of our society yet we can’t understand why. We have developed a propensity for ignoring the spiritual causes of our maladies that have given rise to a victimhood philosophy that has sapped the very strength of the American spirit, giving rise to a litany of social and moral pathologies such as pornography, infidelity, homosexual marriage, abortion and euthanasia. In other words we are knee-deep in a culture of death and the faucet is wide open.

To offset the emptiness in our souls we have vainly attempted to fill it with a culture awash in a flood of sex, exercise, weight reduction programs, jogging, marathons and spa visits to the extent that our lean bodies, which have become our personal idols, stand it stark contrast to our empty souls! This painfully evokes strong Biblical images of whiten sepulchers filled with dead man’s bones. Too many of us have substituted neuroses and psychoses for our venial and mortal sins. We often try to medicate away our feelings of inner conflict.

This is just one facet of the imbalance or the lost of moral homeostasis that our society has created. Just watch television or attend the local Cineplex. It is difficult not to see the nihilism perpetuated in the anti-heroes of the silver screen or on the average sitcom each evening on TV.

I used to read all of Robert Ludlum’s novels many years ago until I noticed that his characters and vapid plots always seemed to meld into a seamless garment of emptiness and despair. His protagonists, more energetic but less philosophical than Hemingway’s existentialist code hero, recognized no other power than their own physical skills or mental acumen. Ludlum’s heroes, especially the long-lived Jason Bourne, had no religious or moral faith. In that he reflected the barren spirituality of our own times. The current and ever-popular Lee Child’s protagonist, the infamous Jack Reacher is cut from the same amoral whole cloth.

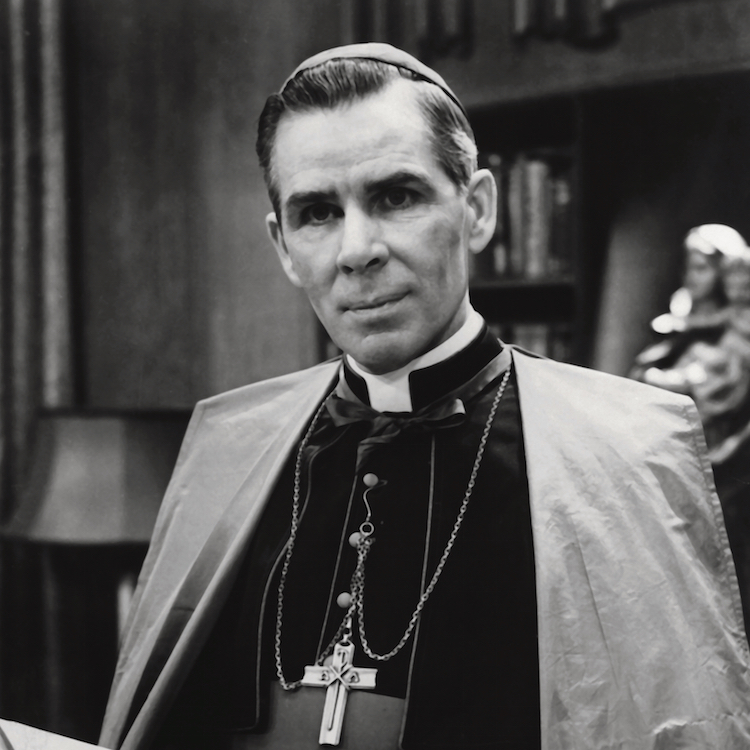

Before the advent of the shrink’s couch and confessional TV, like Mother Oprah, philosophers stressed the need for keeping equilibrium between the spirit and the body. Bishop Fulton J. Sheen, whose TV show Life Is Worth Living used to be more popular than Mr. Television himself, Milton Berle’s show in the 1950s, warned that peace of soul was the only way to rid society of many of its psychological afflictions.

A few presidential candidates, such as Michael Huckabee and Dr. Benjamin Carson seem to be saying the same thing. Bishop Sheen constantly admonished Americans for standing outside the psychiatrist’s’ office when they should be kneeling inside the confessional.

Life in America has become so busy and so demanding that it is too easy to lose sight of our ultimate goal. Like Ludlum’s characters, too many of us never stop to contemplate the question all men and women must ultimately confront — the universal eschatology of what happens at death?

Gen. John Black Jack Pershing underscored this nearly forgotten reality when he challenged his troops, as they embarked from the New Jersey piers in 1918 en route to the war in Europe to consider the three possible outcomes of their service — Heaven, Hell or Hoboken.