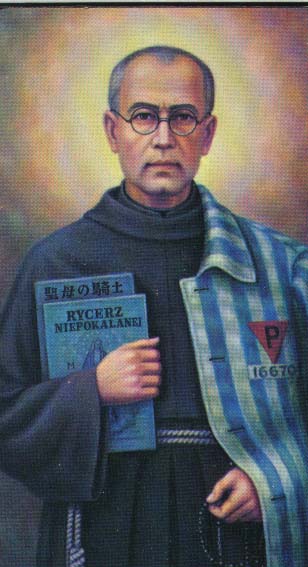

Since this is Holy Week, during which we rightfully focus on the redemptive suffering of Christ, I would like to forego an original essay and instead highlight one of my favorite saints: Maximilian Kolbe. Specifically, I would like to share with the reader the personal testimonies of those who watched Father Kolbe live a life of heroic virtue while a prisoner at Auschwitz. Despite the horrific cruelty and death that surrounded him, Father Kolbe continued to function as a priest, hearing confessions, saying Mass when possible, and encouraging fellow prisoners not to yield to hatred and/or despair. He loved so deeply that he volunteered to take the place of another man who was randomly sentenced to die in a starvation bunker. And it was in that bunker that Maximilian entered into eternity.

(The following testimonies are found in Maximilian Kolbe: No Greater Love, by Boniface Hanley, O.F.M.)

The Nazi guards at Auschwitz were particularly cruel to Father Kolbe. They gave him the most difficult and most disgusting jobs. They often beat him or let guard dogs attack him. When he eventually collapsed from exhaustion, he was sent to the infirmary. Fellow captive Father Conrad Szweda wrote the following:

Father Kolbeʼs face was lined with scars, his eyes lifeless; the fever burned in his body so that his mouth dried out; he could no longer speak. But all were impressed by his manliness and the resignation with which he bore his sufferings. Often he said, “For Jesus Christ, I am prepared to suffer still more.” Even though suffering intense pain, Maximilian heard the confessions of others, prayed with them, and often gave them little conferences on Mary. He was a priest every inch of his burned out body.

Doctor Joseph Stemler, another prisoner, remembered Kolbe:

Like many others, I crawled at night in the infirmary on the bare floor to the bed of Father Maximilian. The greeting was moving. We exchanged some impressions on the frightful crematorium. He encouraged me, and I confessed. Discouragement and doubt threatened to overwhelm me; but I still wanted to love. He helped me to strengthen my belief in the final victory of good. “Hatred is not creative,” he whispered to me. “Our sorrow is necessary that those who live after us may be happy.” His reflections on the mercy of God went straight to my heart. His words to forgive the persecutors, and to overcome evil with good, kept me from collapsing into despair.

A Protestant doctor was also touched by Kolbe:

. . . although tuberculosis consumed him, he remained calm . . . ; through his living belief in God and his providence, with his unshakable hope and, before all else, in his love of God and neighbor, he distinguished himself from all. Although I was in Auschwitz from 1941 until 1945, I knew of no other similar case of such heroic love of neighbor.

The Nazis were pleased to accept Kolbeʼs offer to replace the man chosen to die in the starvation bunker. But even here, his love was greater than the forces of evil. Bruno Borgowiec, an inmate who was forced to remove bodies from starvation bunkers, gave this moving testimony:

In one bunker was Father Kolbe. The cell, with the cold and cement floor, had one ceiling-level window and no furniture. Just a pail for natural needs. The stench was overwhelming. Father never complained. He prayed aloud, so that his fellow prisoners could hear him in order to join him. He had the special gift of comforting everybody. When his fellow prisoners, writhing in agony, were begging for a drop of water, and in despair were screaming and cursing, Father Kolbe would calm them down, inspiring them to perseverance.

After the war, Mr. Borgowiec added the following:

From the cell where these unfortunates were buried alive, you could hear the sound of prayers recited out loud, and the condemned men from other cells would join in. I had to go down once a day to accompany the guards on their inspection tour.

Every time I went down there, I was greeted by fervent prayers and hymns to the holy Virgin whose sound pervaded the whole underground chamber. Father Maximilian would start them out; then everyone joined in.

Sometimes they would be so absorbed in prayer that they did not even realize the guards had come for the daily inspection and had opened their cell door. Only when the SS began shouting at them would they stop praying . . .

Father Kolbe displayed real heroism. He asked for nothing and did not complain.

After the first week, they were so weak they had to recite their prayers in a whisper. Though the others were helplessly prone on the floor, Father Kolbe still greeted the SS inspectors while standing or kneeling among the others, a look of serenity on his face.

The guards knew he had volunteered his life in place of the prisoner who had a family. Once I heard one of them say, “This priest is a real man. I never saw one like him here before.”

After several days, the guards decided to force the issue by injecting Kolbe and four other men with carbolic acid, which caused nearly instantaneous death. Mr. Borgowiec recalled what happened next:

When I was about to carry the body of Father Kolbe out of the cell, and opened the door, I noticed that he was sitting on the floor leaning against the wall, and he had his eyes open. His body was most clean and radiant. Everyone would have noticed this position and everyone would think that this was some saint. His face was bright and serene . . .

On October 10, 1982, Maximilian Kolbe was declared St. Maximilian Kolbe by Pope John Paul II.

During this Holy Week, let us pray to St. Maximilian Kolbe that we, like him, might learn to turn our suffering into acts of love.