Instead of the election campaigning focusing on tax returns of the candidates, it should be centered on the economic implications of income redistribution versus economic growth. Likewise, our energy policies should be focused on debating policies of increasing real employment and not on increasing tax revenues to fund failed policies.

The political debate should be focused on reducing the inequality when such factors as market or monopoly power, in both the product (e.g., gasoline) and productive resource markets (e.g., overcompensated labor and executives), control supply to maximize profits and labor compensation at the cost to everyone of us as consumers.

While it’s bad enough that the number of employed has fallen 1.1 million since December 2008, none of the other employment measures look any better.

We need more of the spirit of Adam Smith, “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices,” and much less of the spirit of Saul Alinsky, “The first step in community organization is community disorganization.”

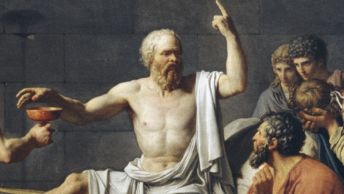

I have often quoted the philosopher, George Santayana, and his warning on what will happen to society if it does not learn the lessons of history.

As social scientists, economists must use history and the results of past economic policies as their laboratory. We cannot take people and evacuate their lungs and light a Bunsen burner and point it at their derrieres, unless we are willing to accept some hard time in our prison system.

But it can be difficult when dealing with the results of past policies. Remember the fears of first President Eisenhower and then President Kennedy as to economic stagnation. I remember lecturing on the distinctions made by James Duesenberry between the short-run or cross sectional consumption and the long-run or time-series consumption functions. The issue at hand was economic stagnation and some argued it was due to weakening consumption as reflected in a cross sectional consumption function. At any given time, those with higher incomes spent a smaller percentage of their income than those of lower incomes, both on an average and marginal basis. As was pointed out, when aggregate consumption was related to aggregate income over time, a different picture emerged showing a more constant marginal propensity to consume. Look elsewhere for the causes of economic stagnation, was the conclusion.

Recall the instituting of a many bracketed progressive income tax that was legislated. The tax brackets were based upon nominal income and not real or inflation-adjusted income. Then came a period of at first gradual and then more rapidly accelerating inflation and what became known as the BRACKET CREEP.

Since nominal incomes rose faster than real incomes, the tax payers CREPT into higher and higher marginal tax brackets or tax rates. As the marginal propensity to pay taxes out of income rose, the marginal propensity to undertake personal consumption expenditures, fell.

This time, economic policies worked – as the tax bracket creep was to a great extent eliminated. A major cause of economic stagnation was eliminated.

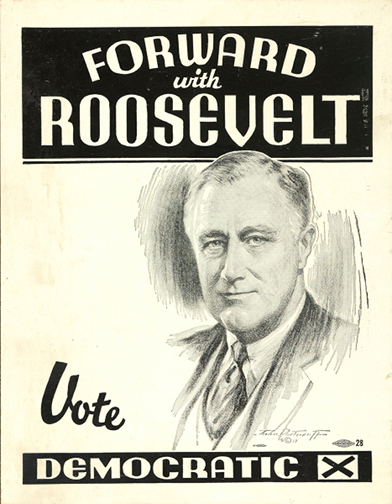

What needs to be done now is to reduce tax rates while we still have some wiggle room before the rising fear of sovereign risk overwhelms investors and eliminates our options. Current policies are sacrificing the wiggle room with increases in the national debt rising faster than the slow rate of GDP growth. The U-6 unemployment rate, the most realistic measure which includes such groups as the discouraged worker, is still at 15%. It sounds a lot like the situation under FDR in the Great Depression of the 1930s as his trusted Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau, Jr. stated in the House Ways and Means Committee on May 9, 1939:

“We have tried spending money. We are spending more than we have ever spent before and it does not work. I say after eight years of this Administration we have just as much unemployment as when we started. … And an enormous debt to boot!”

From a Heritage.org post (Hoover, FDR, and Clinton Tax Increases: A Brief Historical Lesson) of October 20, 2010, we read:

“President Herbert Hoover asked for a temporary tax increase…in June 1932, raising the top income tax rate from 25% to 63% and quadrupling the lowest tax rate from 1.1% to 4%. That didn’t help confidence or the Treasury. Revenue from the individual income tax dropped from $834 million in 1931 to $427 million in 1932 and $353 million in 1933.”

“Unfortunately, President Roosevelt made the same crucial mistake President Hoover made 5 years earlier, so the recovery didn’t last. FDR convinced Congress to raise taxes sharply in 1937 in an attempt to balance the budget. Once tax increases took effect, the economy collapsed into another recession – the second stage of the double-dip which lasted into WWII.”

“…Revenue Act of 1932, signed into law by Herbert Hoover, individual tax rates rose from 25% to 63% at the highest level. Likewise, FDR followed on with a relish, and with passage of the Revenue Act of 1936, the highest marginal income tax rate went to 79% while reducing exemptions and earned income credit at the lower end. By 1940 the federal corporate income tax rate rose to 24% from its 12% level in 1930. Roosevelt also signed laws introducing or raising excise taxes on dividends, a capital stock tax, liquor taxes and higher estate taxes (inter-generational transfer of wealth).”

Following President Herbert Hoover’s tax increase policy in 1932 to control deficits and rising national debt, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) ‘out-Hoovered’ Hoover. The results were dismal and what followed were massive government expenditure increases, especially on public works projects. In 1937, the economy took another dip. The inability to reduce the unemployment rate led to the above cited remarks of Henry Morgenthau in 1939. The clamor of war in Europe and then Asia and FDR’s unpopular decision referred to as Lend Lease in the face of a strongly isolationist public followed by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, finally caused the economy to come back to life, so to speak, but it was really only after WWII that the economy truly sprang back to life after Congress removed many of the regulations (e.g., price controls) put in place prior to and during the conflict.

Gene Smiley offers wise insight regarding the Depression:

“It is commonly argued that World War II provided the stimulus that brought the American economy out of the Great Depression. The number of unemployed workers declined by 7,050,000 between 1940 and 1943, but the number in military service rose by 8,590,000. The reduction in unemployment can be explained by the draft, not by the economic recovery.”

Tax rate increases are not always disruptive. As the U.S. entered the Second World War, in order to successfully pursue that war, it became an issue of guns versus butter, as it was then expressed. Peacetime goods and services had to give way to more wartime goods and services. Rationing was instituted and FDR asked Congress for huge tax rate increases and they so legislated them.

It wasn’t until the Revenue Act of 1945 was passed (cutting tax rates) by a Democratic Congress that prosperity finally returned.

In an April 12, 2010 Wall Street Journal article (Did FDR End the Depression?), Burt and Anita Folsom note:

“Roosevelt died before the war ended and before he could implement his New Deal revival. His successor, Harry Truman, in a 16,000 word message on Sept. 6, 1945, urged Congress to enact FDR’s ideas as the best way to achieve full employment after the war.”

“Congress—both chambers with Democratic majorities—responded by just saying “no.” No to the whole New Deal revival: no federal program for health care, no full-employment act, only limited federal housing, and no increase in minimum wage or Social Security benefits.

Instead, Congress reduced taxes. Income tax rates were cut across the board. FDR’s top marginal rate, 94% on all income over $200,000, was cut to 86.45%. The lowest rate was cut to 19% from 23%, and with a change in the amount of income exempt from taxation an estimated 12 million Americans were eliminated from the tax rolls entirely.

Corporate tax rates were trimmed and FDR’s “excess profits” tax was repealed, which meant that top marginal corporate tax rates effectively went to 38% from 90% after 1945.”

The authors go on to explain that in spite of the lower tax rates, tax revenues grew within a few years, exceeding the receipts from during the war years when rates were significantly higher.

Fast forward…

As we entered the War in Vietnam, President Lyndon Johnson similarly asked Congress for tax rate hikes and facing rising inflationary pressures received them. His problem, as has been analyzed many times over, was the temporary nature of the tax rate increases. Permanent income hypothesis supporters argued that this approach could not do the job and did not do the job of suppressing inflationary pressures although it did to some extent free up productive resources by reducing some production of peacetime goods and allow more wartime goods to be produced.

While sunset limits to tax rate changes, both upward and downward, sound good, the warning of supporters of the Permanent Income Hypothesis as to their efficacy, should be seriously considered.

The Clinton tax rate increases give evidence of the danger of permanent tax rate increases over an extended period of time. Under the insistence of Secretary of the Treasury Rubin, President Clinton asked Congress to direct significant tax increases passed in 1993, not only to eliminate budgetary deficits but to reduce the national debt in an absolute and not just in a relative sense. Congress concurred and so legislated.

Remember that tax revenues are a product of the tax rate and the tax base. The tax rate changes, especially permanent changes, have a fairly strong impact on the tax base. What is involved in this analysis of such tax rate changes is the concept of elasticity. What will be the response of the tax base to the change in tax rates?

Of equal importance is the time pattern it takes for such responses to have their effects not only on the tax base but the growth rate of GDP. In this case, all seemed well from the inception of the tax rate increases until the last year of Clinton’s second term in 2000 when the economy literally collapsed. As the federal government’s deficits shrank and then turned into surpluses, the fiscal pressure exerted on the economy finally manifested itself with the growth rate moving from a positive 6.4% annualized quarterly real GDP rate in the 2nd Quarter of 2000 to a negative 0.5% in the 3rd quarter 2000.

This proved to be one of the sharpest downturns in the nation’s economic history. The incoming President Bush asked for and eventually received tax rate reductions, but with sunset limits. Here we go again, back to the efficacy of temporary tax rate changes as discussed above.

Again, the historical record gives support to (more permanent) tax rate cuts as a successful way to return the economy to recovery and growth. During the presidencies of Harding and Coolidge, and at Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon’s urging, Congress reduced tax rates in 1921, 1924 and 1926. This succession of tax cuts resulted in a strong upturn in the U.S. economy.

According to Wikipedia, Andrew Mellon “…proposed tax rate cuts, which Congress enacted in the Revenue Acts of 1921, 1924, and 1926. The top marginal tax rate was cut from 73% to 58% in 1922, 50% in 1923, 46% in 1924, 25% in 1925, and 24% in 1929. Rates in lower brackets were also cut substantially, relieving burdens on the middle-class, working-class, and poor households.

By 1926 65% of the income tax revenue came from incomes $300,000 and higher, when five years prior, less than 20% did. During this same period, the overall tax burden on those that earned less than $10,000 dropped from $155 million to $32.5 million.”

As mentioned above, fears of economic stagnation led both Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy to the push for lower tax burdens.

The arguments of Arthur Laffer had some influence on President Reagan as he convinced Congress on the need for tax rate reductions. The economy did well for a number of years.

In a June 6, 2010 Wall Street Journal opinion column, Arthur Laffer argued that…“What was needed then and is needed now is a decrease in tax rates in order to grow the tax base. Remember that tax revenues are equal to the tax rates times the tax base such a GDP. The ‘Reagan tax rate reductions’ and the ‘Bush II tax rate reductions’ were followed by relatively long periods of significant economic growth (Reagan in particular; note that Bush’s recovery was stalled by the financial collapse, beginning in late 2007).”