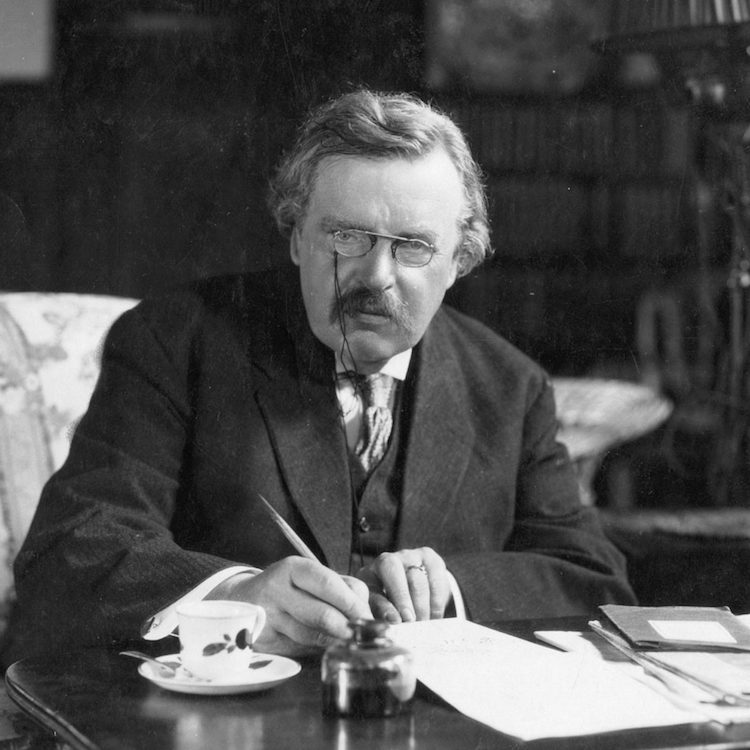

An American tourist remembers seeing him standing in the doorway of a pie shop, writing a poem. At 6’2” with a tremendous girth, he most resembled an upright blimp. With his untidy clothes, unruly hair and mustache, he was a familiar figure on London’s Fleet Street, sometimes composing his articles while walking, occasionally leaning against a wall to write, but most often seated in a café.

The man was Gilbert Keith Chesterton, aka GKC—poet, novelist, playwright, critic, journalist, illustrator, lecturer, radio broadcaster, and defender of his adopted Catholic faith.

GKC had the rare but felicitous habit of distinguishing between the idea and the person who expressed it. In attacking ideas he showed no mercy, but he seldom treated opponents with anything but respect.

Authorities on St. Thomas Aquinas hailed Chesterton’s biography of the saint the best ever written about him. The famous Aquinas scholar Etienne Gilson admitted that he could not have duplicated the book after a lifetime of studying Aquinas. (Chesterton is said to have composed it in his typically casual manner.)

When a critic remarked cynically that he would begin to examine his own philosophy when Chesterton stated his, Chesterton accepted the challenge and produced Orthodoxy, a penetrating statement of the sanity of Catholicism. A later GKC book, The Everlasting Man, brilliantly attacked the idea that the Gospels were like pagan myths.

At a time when many intellectuals were relativists, obliterating distinctions between truth and nonsense, and questioning even their own existence, Chesterton wrote, “Supposing there is no difference between good and bad, or between false and true, what is the difference between up and down?” He was “incurably convinced that the object of opening the mind, as of opening the mouth, is to shut it again on something solid.”

He was equally quick at spotting inconsistencies in the arguments of his opponents. For example, he questioned why those who disapprove of the contemplation of religious images are so quick to worship the Eastern mystic who “only contemplates his big toe.” He noted that one thinker denied human free will and then proceeded to blame the Prussians for invading Belgium. How could they be blamed, he wondered, if there were no free will? For that matter, why should we say “Thank you” to someone for passing the mustard?

Chesterton found it humorous that the new theologians of his day admitted “divine sinlessness, which they cannot see even in their dreams,” but “essentially denied human sinfulness, which they can see in the street.” And he was amused by the fact that those who reject dogma do so dogmatically.

His definitions were especially incisive. A Puritan is “a person who pours righteous indignation into the wrong things.” “Psychology is the mind studying itself instead of studying the truth.”

To the theory that man is nothing more than an animal, Chesterton responded by enumerating the things that man has done that no animal has ever done—painting, building, thinking, writing—and decided that in all these things that really matter, men are really very unlike animals.

Chesterton became a Catholic in 1922 and was fond of pointing out that he did not begin adulthood as a believer, but that it was the absurd nonsense that atheists and agnostics wrote that made him a believer. He was proud of his religion, proud of dogmas, of veneration of Mary, of belief in the Trinity, the Mass, the Papacy, and Confession. And he was very aware of the reality of evil. When others denied sin, he said humbly that their lives must have been more innocent than his.

Chesterton died on June 14, 1936. One of his sayings well described his approach to life: “A thinking man must always attack the strongest thing in his time. For the strongest thing is always too strong.” He was an intellectual giant who lived in the wonder and simple honesty of a child. His mark on the 20th century was indelible.

Copyright © 2015 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved