While Clint Eastwood’s stark movie, Flags of our Fathers, portrayal of the deadly battle for Iwo Jima in World War II was virtually ignored by his Hollywood peers in 2007, it had a strong impact on the general public who revered the heroism that his portrayal of American troops displayed.

Despite its violence, the main thrust of Flags was the home-front struggles of the three survivors in dealing with the instant fame their heroic act brought. Drafted as spokesmen for war bond sales, they quickly adopted the creditable tag line that the real heroes of Iwo were those men who died there.

Based on the book of the same name Flags of our Fathers sparked many a debate on the meaning of hero.

In 1950 my father took me to see John Wayne in The Sands of Iwo Jima. Even at age seven, though I found war movies exciting, my concept of hero was reserved more for the baseball diamond than any tale of sanguinary combat.

The Brooklyn Dodgers were the darling underdogs of the 1950s. While they won a number of pennants (5) they always lost to the New York Yankees in the World Series — except in 1955.

While all the Dodgers were heroes that year, to my adolescent mind, the quiet Kentuckian at shortstop, Pee Wee Reese, represented to me everything a hero should be.

He was the team’s leader, and he played the game with the same grace and dignity that my contemporaries in St. Louis must have seen in Stan The Man Musial. (He did not destroy my childhood ideals when I interviewed him in his home late one July night in 1972.)

When Reese was inducted into the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown in 1984, I was there to honor him.

A number of years ago during an All Saints’ Day Mass the celebrant priest labored unsuccessfully for a proper analogy to underscore the Holy Day. During the course of his painful musings it dawned on me that when the Church canonizes a saint, it could be viewed as the Catholic equivalent of putting a baseball player in the Hall of Fame.

It was St. Paul who first recognized that faithful Christians could easily be analogized as athletes who had fought the good fight and finished the good race. An English professor at Holy Cross had used those same parallels during my freshman orientation in 1961.

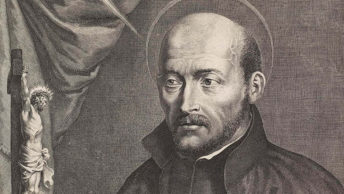

In effect Catholic saints are our spiritual and moral athletes, who have successfully fought the good fight and run the good race. The Church was recognizing that they had played the game of life with the practiced skills of faith, hope and charity.

Their lives still serve as constant reminders that if we only have the athletic discipline of daily sacrifice and loving charity, we will someday break the ribbon of victory in eternity. Many saints also showed a kind of dangerous courage possessed by many athletes to stare death and evil in the face, ultimately paying the full price for their faith in God.

What Yogi Berra, Lou Brock, Bob Gibson, Mickey Mantle and Musial are to baseball fans, Sts. Joseph, Peter, John Paul II, Theresa, Catherine and Anthony are to Catholics. They are our heroes for all seasons.

After the passage of the Fetal Tissue Use Amendment, I learned that a friend had resigned his position with a prestigious law firm because it had represented one of the principal supporters of the pro-cloning amendment.

I was inspired by his heroic stand in a social atmosphere where apathy is the everyday choice of too many Catholics.

To the point of our mutual embarrassment, I told him he was my new hero.

Had he been familiar with Flags, I suspect, like the survivors of Iwo, he would have said the real heroes of the faith were those who had died for it.

Nonetheless, his principled stand on a culture war battlefield is morally as significant as that tiny volcanic island in the Pacific.

While most of us may never be asked to make the ultimate sacrifice, all of us have to suffer these daily small deaths to ourselves to prepare for, if not the Hall of Fame in the sky, at least for a seat in the stands.