My former pastor once referred to his special place, a remote location on a farm in Illinois where as a youngster he pondered his vocation to the priesthood. I believe everyone needs a personal sanctuary where the hustle and bustle of daily life cannot intrude.

One place that I love to visit to think and pray about things is Our Lady Chapel, behind the main altar in New York’s St. Patrick Cathedral. Every time we visit my hometown, my wife and I make it a point to stop there for a few minutes of prayer and meditation.

Adjacent to the small chapel is the tomb of Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen. No Catholic thinker had a greater impact on my Catholic upbringing than he. As an adolescent, I devoured his books, such as Life is Worth Living, Go to Heaven and Three to Get Married with a passion that continues to this day. As an adult, I still come back to Sheen when I need a spiritual uplift. One of his best books was his 1958 classic The Life of Christ in which he introduced me to British mystic Caryll Houselander.

Born in 1901, Houselander found her early life beset by illness, parental divorce, religious doubts and even the harrowing Zeppelin attacks that terrorized London during World War II. After reconciliation with the Church she published her seminal work, Wood of the Cradle, Wood of the Cross, which had been formerly known as Passion of the Infant Jesus, an almost mystical union of the manger and the cross. Her vivid image of cradle and wood reappeared as the title of her autobiography, A Rocking-Horse Catholic.

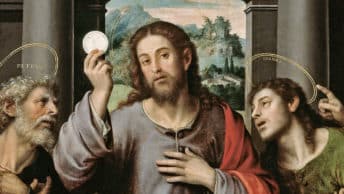

Along these same lines, Bishop Sheen cited one of her most profound literary images: Bethlehem is the inscape of Calvary, just as the snowflake is the inscape of the universe. Inscape is a neologism, minted by Gerard Manley Hopkins, a 19th-century Jesuit mystic poet whose verse in turn had inspired Houselander. The word, which does not appear in my latest Webster’s, provides an inner vision that reaches beyond a singular event, pointing to a greater event to come. It is the mirror image of landscape, which is a broad panoramic view.

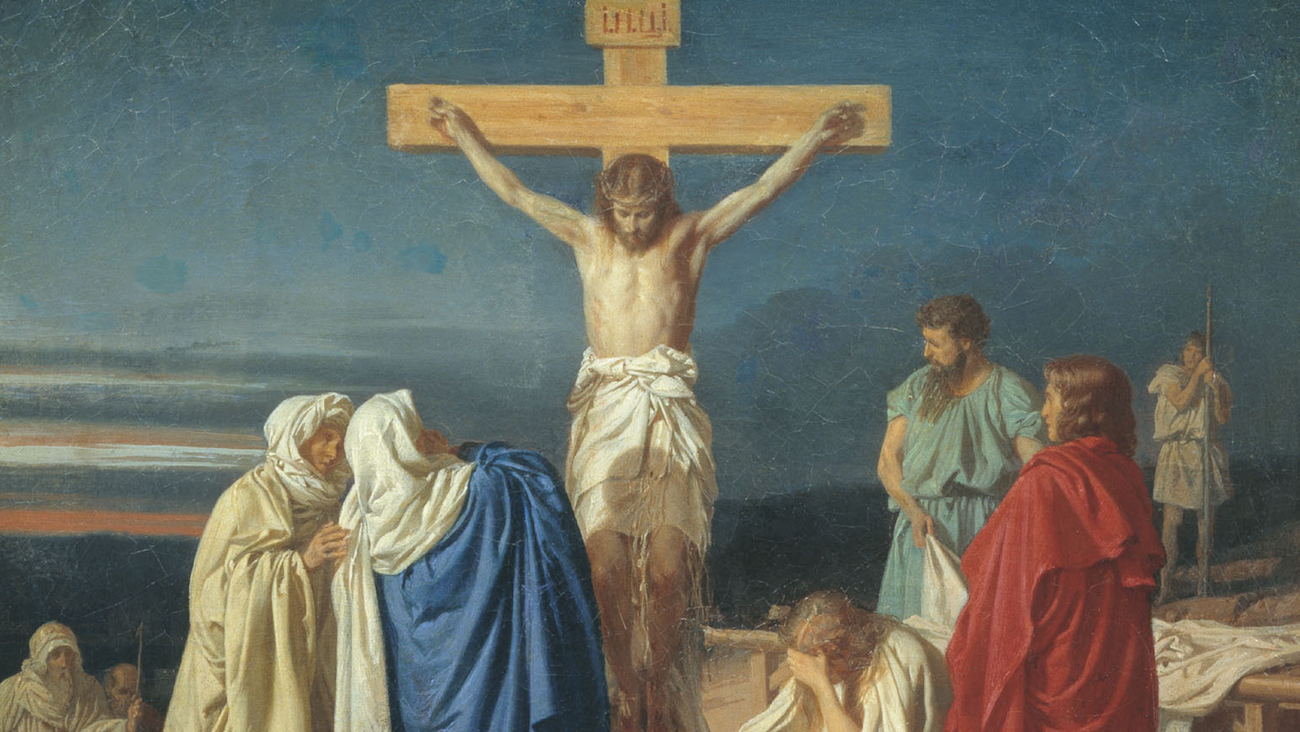

Houselander believed that Christ’s heavy wooden cross cast a dark shadow over the newborn, lying in his tiny wooden cradle in the tiny Bethlehem cave. Like the mythical Sword of Damocles, its dark image menacingly portended the dusty mound of Calvary. As part of his redemptive destiny, Jesus accepted the humility of his birthplace in the manger because there was no room in the inn. At his death, he accepted the humiliation of the cross because men did not have any room in their hearts for him.

How important is all of this for us? Without the Incarnation, there would have been no salvific history and the rusty gates of Heaven would have been locked for all eternity. As an aside, Hollywood, in its own materialistic way, has also recognized the relationship of Bethlehem and Calvary. Because of the box-office success of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, it released The Nativity Story in 2009. This movie is a proud testament that Hollywood, at least for the moment, has once again recognized religious subjects as a part of mainstream entertainment.

Its production was a positive sign since even the mention of Christmas drives secular-minded people to indifference, distraction and even hostility. What better time is it for us to think about this providential link between Christ’s cradle and his cross than during the Lenten hiatus between Christmas and Easter? Their implicit nuptials should give us pause for prayerful thanks, perhaps even in our special places.