The Holocaust- Atrocities in Poland and Croatia

In March 1998, the Vatican released a statement on the Catholic Church and the Holocaust entitled: “We Remember: A Reflection on the Shoah.” The document was intended to heal the rift between the Church and the Jewish Community for wrongs suffered during the Holocaust. Unfortunately, it was not well received by Jewish leaders. Surveying Jewish reactions to the statement, Kevin Madigan reported his findings in CrossCurrents (Winter 2000/2001). He notes: “In terms of specific criticisms, virtually all Jewish commentators faulted the document for failing to acknowledge the deep connection between ecclesiastically sponsored anti-Judaism and the anti-Semitism that achieved such disastrous expression in the Shoah.”[92] Madigan also indicates that the reaction to Pius XII was particularly unfavorable, “Virtually no Jewish commentator, even those who responded favorably to ‘We Remember’ as a whole, applauded the document for its representation of Pius [XII], and very, very few spoke favorably of his activities on behalf of menaced Jews during the war.”[93] It was in Poland where the Holocaust drama would begin.

On August 23, 1939, a non-aggression pact was signed between Germany and Russia better known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact named after the two foreign ministers who negotiated the treaty. In addition to agreeing that neither nation would form an alliance with an enemy combatant, the pact also provided a protocol for how Poland would be divided up between Russia and Germany. Poland had one of the largest populations of Catholics and Jews in Europe with over 20 million Catholics and three million Jews living within its borders.[94] The fate of the Baltic nations including: Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Finland to the north were also held in the balance. The agreement was seen as a major set-back to the Vatican because the Nazis were viewed as an ally against the spread of atheistic Communism. John Conway calls the alliance “most hostile to the Church’s interests, and the consequent Blitzkrieg destruction of Catholic Poland were grievous blows.”[95]

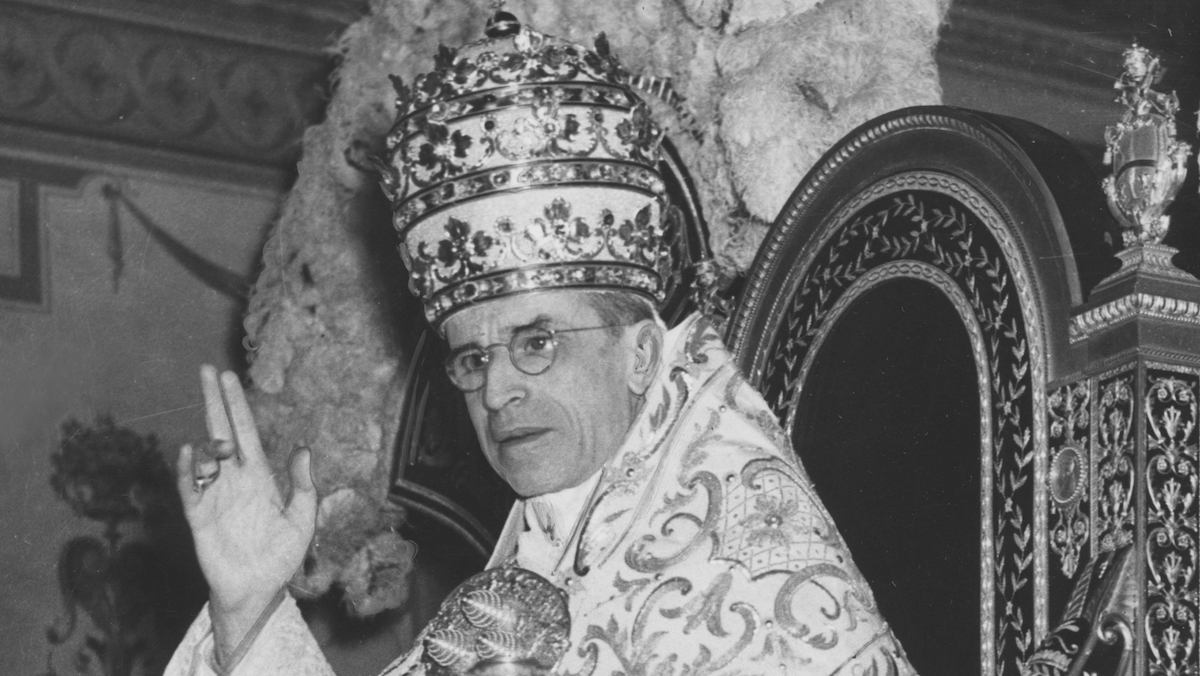

Once the pact with Russia was signed, Germany attacked Poland on September 1, 1939. Weeks later, the Polish army capitulated to the Wehrmacht forces at which time the doors opened wide for SS squads to follow through and take control of the occupied territories. Jews and Polish intellectuals were executed. Catholic priests were sent to prison camps and Jews who were not killed by the SS were shipped off to various ghettos the largest of which was located in Warsaw the capital. Word quickly reached the Vatican that atrocities against Jews and Catholic priests were occurring with frequency. Jews converted to Christianity were not exempt. On October 20, 1939, Pope Pius XII issued his first encyclical Summi Pontificatus in which he expressed his deep concern over events in Poland:

Venerable Brethren, the hour when this our first Encyclical reaches you is in many respects a real “Hour of Darkness” (cf. Saint Luke xxii 53), in which the spirit of violence and of discord brings indescribable suffering on mankind….The blood of countless human beings, even non-combatants, raises a piteous dirge over a nation such as our dear Poland which…has a right to the generous and brotherly sympathy of the whole world.[96]

Despite the fact that the encyclical did not mention Hitler or the Nazis, the Nazi diplomatic corps took offense to the proclamation but did nothing to incite wrath on the part of the Church.

Cardinals at the Vatican were also troubled that the Pope did not speak out against the atrocities perpetrated by the Nazis in more specific terms. In June 1940, Cardinal Tisserant of France wrote to Cardinal Célestin Suhard, “I am afraid history will reproach the Holy See for following the policy of convenience for itself, and not much more.”[97] Daniel J. Goldhagen indicts the Pope for his inaction in the face of mounting evidence of atrocities against Jews:

The death factories, with their gas chambers and crematoria, had long been consuming their victims day after day. For all this time that the Germans and their helpers were killing all these Jewish men, women, and children, across the continent, Pius XII publicly said nothing. He uttered no protest even though he knew the broad contours of the destruction, having received a stream of detailed reports about the ongoing mass murder.[98]

Drawing on his experiences from 1917 in trying to negotiate peace proposals with German officials during World War I, the Pope was faced with a terrible dilemma as Conway explains: “Pius XII still entertained hopes of a compromise peace, and any criticism of Germany would, he believed, serve only to destroy the Vatican’s potentiality as a diplomatic medium for the negotiation of peace.”[99]

By 1941, conditions quickly deteriorated in Poland for both Catholic clergy and the Jews. Bishop August Hlond of Warsaw wrote to the Cardinal Secretary of State Luigi Maglione “we suffer with anxiety and doubt whether it is the will of God to continue to hide such iniquity with the veil of profound silence.”[100] In November 1941, Archbishop Adam Sapieha of Cracow also wrote to Maglione admonishing the Pope to speak out:

For the good of the church I dare say humbly to observe that…an expression of protest and blame on the part of the Holy See would be indispensable…It may be said that the Catholic world expects the defense of justice, even if the said defense would not change the manner of action of the German government.[101]

Despite these pleas, the Pope remained silent.

The crisis would deepen in Poland after Germany invaded Russia on June 22, 1941. A letter dated September 26, 1942 from President Roosevelt’s special representative to the Vatican, Myron C. Taylor, to the Cardinal Secretary of State Luigi Maglione confirmed that atrocities against the Jews continued unabated: “These mass executions take place, not in Warsaw, but in especially prepared camps for the purpose, one of which is stated to be in Belzec. About 50,000 Jews have been executed in Lemberg itself on the spot during the past month.” Taylor concluded the letter with a request for aid from the Pope, “I should like to know whether the Holy Father has any suggestions as to any practical manner in which the forces of civilized public opinion could be utilized in order to prevent a continuation of these barbarities.”[102] The pope remained silent. He feared that his intervention would only make matters worse for the Jews.

In April 1941, the German army marched into Yugoslavia and set up a puppet government in Zagreb under the leadership of Ante Pavelić and his Ustasha movement for an independent State of Croatia. Like the Nazis, the Ustasha used brutal measures to racially “purify” the nation of Serbs, Jews, and gypsies. It is estimated that over 350,000 Serbs were killed in the racial cleansing, 30,000 Jews and between 15,000 to 27,000 Roma.[103] Those killed had their property confiscated by the State. Emily Greble Balić provides some background of what the Ustasha tried to accomplish, “The Ustasha believed that developing a Croatian state required immediately purging the country of non-Croats, purifying the Croatian language, and imposing a unified Croatian cultural and ideological agenda at all costs.”[104] One method used to “purify” the Serbs was mass conversions to Roman Catholicism. To obtain guidance on this “missionary” venture, Pavelić was privileged to have an audience with the Pope in May 1942 despite a protest from a Yugoslavian envoy.

The cruelty unleashed by the Ustasha can only be matched by the worst atrocities accorded to the Nazis. In a letter dated July 10, 1941, the German Chargé ď Affaires in Croatia named Troll wrote of the Croatian brutality to the German Foreign Minister:

The Serbian question has become considerably more acute in the last few days. The ruthless carrying out of the resettlement with many unfortunate by-products, and numerous other acts of terror in the provinces in spite of the strict decree of June 27, 1941 by the Poglavnik [Pavelić] are given even the sober minded Croatians circles reasons for serious concern.[105]

The Germans also allowed the Ustasha to run their own prison camps, the most notorious of which was Jasenovac. On February 22, 2010, The Jerusalem Post featured an article by Julia Gorin in which she outlines in full detail the Vatican complicity with the Ustasha:

It has been 60 years, and the world still doesn’t know the story of wartime Croatia, where not only did the Vatican not speak out against crimes, not only was it complicit in the genocide of a million people, but it subsequently never expressed remorse for the spilled Orthodox blood as it’s done for Jewish blood.[106]

Amidst the carnage, Catholic priests and the Archbishop of Zagreb Aloysius Stepinac were also accused of taking part in the Ustasha regime. In 1946, Stepinac was arrested in Yugoslavia and tried for war crimes and sentenced to 16 years in prison:

It was furthermore established that Archbishop Stepinac played a role in governing the Nazi puppet Croatian state, that many members of his clergy participated actively in atrocities and mass murders, and, finally, that they collaborated with the enemy down to the last day of the Nazi rule, and continued after the liberation to conspire against the newly created Federal Peoples Republic of Yugoslavia.[107]

Despite his arrest and conviction, Stepinac was blessed as a Cardinal by Pope Pius XII in 1953 and beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1998.

John Morley presents evidence in his book Vatican Diplomacy and the Jews (1980) that Pius XII’s Cardinal Secretary received numerous reports from his representative in Croatia about Jewish deportations to Germany and certain death:

In all these contacts, however, with one possible exception, there is no evidence of a protest against or condemnation of the actions taken by authorities against the Jews…The record of Croatia on the Jews is particularly shameful, not because of the number of Jews killed, but because it was a state that proudly proclaimed its Catholic tradition and whose leaders depicted themselves as loyal to the Church and to the Pope.[108]

In November 1999, legal proceedings of the Serbian genocide by the Ustaha made headlines when a group of Holocaust survivors sued the Vatican Bank in the United States Ninth Circuit Court in California in the case Alperin vs. Vatican Bank. The trial involved the recovery of compensation by Holocaust survivors who claimed that gold was stolen from Jews and shipped to the Vatican Bank. The case was dismissed and appealed a number of times until 2009 when the Court of Appeals ruled that the Vatican Bank enjoyed special status, namely, immunity from prosecution because of the Sovereign Foreign Immunity Act. [109]

Guenter Lewy makes a serious charge against the legacy of Pius XII in asserting that the Pope took a cautious pro-German posture on the conflict in the East even after the Wehrmacht suffered severe losses after the Battle of Stalingrad in February 1943: “The desire of the Holy See not to weaken the German power of resistance against Russia was one of the most important reasons why all efforts on the part of the Allies failed to persuade the Vatican publicly to denounce German atrocities, including the extermination of the Jews in Europe.”[110]

Did the destruction of Communism mean more to the Pope than the destruction of the Jews?

Nazi Occupation of Rome-September 1943

The summer of 1943 was one of the most tumultuous years in the history of Italy. On July 19, the Pope’s greatest fear came to pass when Allied bombers struck the historic Church of San Lorenzo in Rome killing 700 civilians and injuring an additional 1,500. In an unprecedented show of sympathy, the Pope rushed to the scene of the devastation and “knelt down in the rubble and prayed for the victims of this and other raids.”[111] The following day, the Pope fired off a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt mourning the loss of innocent civilian lives and pleading once again for the Allies to spare the city of Rome:

But since Divine Providence has placed us head over the Catholic Church and Bishop of this city so rich in sacred shrines and hallowed, immortal memories, we feel it our duty to voice a particular prayer and hope that all may recognize that a city, whose every district, in some districts every street has its irreplaceable monuments of faith or art and Christian culture, cannot be attacked without inflicting an incomparable loss on the patrimony of Religion and civilization.[112]

The President made no promises but the bombings continued. On July 24, 1943, the Grand Council of Fascism in Rome convened as Allied troops moved into Sicily. At the assembly, Dino Grandi delivered an impassioned speech blaming Mussolini for betraying the Italian people when he aligned with the Nazis.[113] The next day, King Victor Emmanuel ordered the arrest of Il Duce and a new government was installed under the leadership of Marshal Pietro Badoglio. A diary entry of Joseph Goebbels dated July 27, 1943 recorded events that transpired at Nazi headquarters after Mussolini’s fall:

According to reports reaching us, the Vatican is developing feverish diplomatic activity. Undoubtedly, it is standing behind the revolt (against Mussolini) with its great world embracing facilities. The Führer at first intended, when arresting the responsible men in Rome, to seize the Vatican also, but [Joachim von] Ribbentrop [Nazi Foreign Minister] and I opposed the plan most emphatically.[114]

By September 8, Italy announced an armistice with the Allies and 75,000 British POWs literally walked out of prisons 4,000 of whom headed to the Vatican seeking food, clothing and shelter.[115] Hitler was enraged. In a daring rescue, German paratroopers liberated Mussolini on September 12 and set up a puppet government in Salò. The main concern at the Vatican was whether Hitler would send his troops into Rome and take control of the city. The Vatican, at the time, was in a rather compromising position by hosting a number of Allied diplomatic operations including D’Arcy Osborne of Great Britain and Harold Tittmann, Jr. of the United States. As previously noted, when Italy entered the war in June 1940, the Allies cut off diplomatic relations and the diplomats were permitted by the Pope to move their operations into Vatican City.

According to McGoldrick, the Vatican provided funds for Osborne in 1943 to run a rescue operation for the British POWs under the noses of the Nazis.[116] Clearly, Pius XII was taking a major risk collaborating with the British. Meanwhile, German forces were retreating up the peninsula after Allied troops landed in Sicily and Salerno. In Milan and other cities to the north, American and British bombers continued their onslaught in the air over German positions. Rome was the next target despite multiple pleas from the Pope to spare the city and its priceless monuments. Bombers hit strategic rail lines and military installations in the city but also caused collateral damage to civilian locations.

By early September 1943, Italy signed an armistice agreement with the Allies and the king and his new prime minister fled to safer territory in southern Italy where the Allies continued pushing Wehrmacht troops further north.

The question whether Hitler would storm the capital was answered on September 10, 1943. Nazi troops under the command of Field Marshall Albert Kesslering occupied Rome along with a contingent of SS squads and Gestapo led by General Karl Wolff and Colonel Herbert Kappler. Needless to say, the Pope was alarmed by the German occupation. Soon, he would find out that Hitler was planning to have him arrested and sent to Germany if he spoke out against the German occupation. At the time German forces took control of the capital, there were approximately 8,000 Jews living in Rome. On September 26, Kappler met with Jewish leaders and demanded fifty kilograms of gold in thirty-six hours or else 200 Jews would be arrested and shipped out of Italy.[117] Many Jews had already fled Rome when word spread that the Germans were about to take over the city, however, Jewish leaders quickly met and began to accumulate gold from members of synagogues and other civic organizations. The Jewish leaders also made a request to the Vatican asking for gold should the need be required. The Vatican agreed to lend gold to the Jews if needed. It was not. The Jews were able to accumulate sufficient gold from rings and other jewelry to meet the SS demands and the ransom was paid. Thinking that the lust of Typhon was satisfied, the Jews that remained in the city continued with their daily routines expecting little harassment. They were sorely mistaken. On September 29, the Nazis stormed the main synagogue in Rome and began looting rare books and manuscripts. Matters would only get worse. By October, Hitler demanded that Jews be rounded up and shipped to concentration camps. Kesselring wanted nothing directly to do with genocide and deferred the operation to the SS. Meanwhile, General Wolff and his assistant Eugen Dollmann with the cooperation of German Ambassador to the Vatican Baron Ernst von Weizsäcker were trying to do all they could to convince Hitler that the operation would cause social unrest in the city and angry protests from the Pope that would result in serious ramifications for German Catholics. Wolff then secretly advised the Pope that should he speak out in protest, Hitler would have him arrested and shipped to Germany. In a last ditch effort to dissuade Hitler from carrying out the plan, Wolff met with the Chancellor on October 7 in his East Prussian headquarters. Hitler did not relent. On October 16, SS troops fanned out across the city and began arresting Jews. According to Kurzman, over 4,000 Jews found refuge in convents, monasteries and Castel Gandolfo, the Pope’s summer residence.[118] Two days later, over 1,000 Jewish women, children, and elderly were packed into trains and sent to Auschwitz. The Pope said nothing publicly to denounce the atrocities, however, the Vatican Cardinal Secretary Luigi Maglione met with von Weizsäcker to protest and, surprisingly, the arrests stopped the next day.

With Mussolini ousted from power and out of Rome, the Italian Resistance became more menacing for the Nazis. On March 23 1944, a group of Gapisti (GAP) partisans from the Communist underground movement packed a cart with explosives as a regiment of German SS police were marching along the Via Rasella near the Piazza Barberini. At around 2 p.m. the bombs detonated killing 32 soldiers and seriously wounding several others. The commanding officer, General Kurt Mälzer, who was not present at the time of the attack, arrived to a scene of bloodshed and destruction. In a rage, he threatened to blow-up the entire block and kill all the residents who were rounded up. He relented however, subject to Hitler being advised of the attack with further instructions. Hitler promptly approved retaliation within twenty-four hours with the murder of ten Italians for every German soldier killed. The next day March 24, Kappler’s SS men rounded up 335 Italians mostly political prisoners including Jews and marched them to the caves at Ardeatine where they were summarily executed. The Pope again made no public statement.

As the Allies continued to push north, Nazi troops and SS squads fled Rome and the city was eventually liberated in September 1944. Mark Riebling summarizes what occurred during the Nazi occupation of Rome:

During the German occupation, the SS had arrested 1,007 Roman Jews and sent them to Auschwitz. Fifteen survived. Pius said nothing publicly about the deportations. Over the same period, 477 Jews were hidden in Vatican City, and 4,238 received sanctuary in Roman monasteries and convents.[119]

Once the German troops left the city, the Pope made a public appearance on the balcony overlooking St Peter’s Square to the cheer of thousands of adoring worshippers.

After the war, the Vatican played a major role in assisting refugees from various countries who flocked to Rome seeking aid. Among the throngs of displaced homeless men, women, and children were wanted Nazi war criminals. Mark Aarons and John Loftus argue in their book Unholy Trinity (1991) that the Holy See provided “ratlines” for Nazis in hiding seeking to escape to South America. Specifically, the authors note that Bishop Alois Hudal was chosen by Pius XII to serve as “Spiritual Director of the German People Resident in Italy.” Among those who Bishop Hudal knowingly assisted with International Red Cross Passports and cash was Walter Rauff, an SS Officer who oversaw the development of mobile gas trucks used to kill Jews[120] and Franz Stangl, the Commandant at Treblinka concentration camp. [121]

The occupation of Rome by the Nazis pushed Pius XII to his diplomatic and ecclesiastical limits. With Jews in hiding throughout the city in monasteries and convents, with Allied foreign ministers housed inside the Vatican filing reports, with concerns whether the Gestapo would begin pillaging Vatican art treasures, and with the knowledge that a plan was in place to arrest the Pope and ship him off to Berlin, Pius XII stood firm in the face of adversity. While he did not speak out about Jews being rounded up by the SS and shipped off to Auschwitz, he did authorize numerous church properties including his vacation home to be used as safe havens to hide Jews.

Regarding post-war “rat-lines,” it would be hard to conceive that the pope would willingly aid and abet the escape to South America of wanted Nazi war criminals. In all likelihood, he never got personally involved in the daily distribution of provisions but merely delegated the task to his friend Bishop Hudal. Hudal, on the other hand, obviously had his own agenda. If Pacelli is to blame, it is for a lack of good judgement in assigning such an important task to Hudal.

Historiography – The Silence of Pius XII

As evidenced in this paper, there are numerous authors, writers, and scholars who have weighed in on the controversial life and work of Eugenio Pacelli. The historiography on the topic is prodigious and spans from the early 1960s to the present day. The vast majority of the authors referenced here are of the opinion that the Pope should have been more outspoken in his condemnation of Nazi and Fascist anti-Semitic policies and atrocities perpetrated against the Jews. Unlike his predecessor, Pope Pius XII followed a more diplomatic approach in dealing with Vatican affairs and foreign policy in his quest to maintain Church autonomy and neutrality throughout the war years.

From all indications, the firestorm surrounding Pius XII’s “silence” during the Holocaust originated when The Deputy, by Rolf Hochhuth appeared on the Berlin stage in 1963. The play was referenced in nearly all the works cited in this paper for its critical assessment of the Pope’s inaction during World War II. Once the Catholic Church initiated a rebuttal defense of the embattled Vicar of Christ, scholars began to further investigate the matter and demand the release of Vatican archives covering the period in question. Even the play itself was not without controversy. In January 2007, the National Review printed an explosive article by Ion Mihai Pacepa, the highest ranking officer in Romanian Intelligence, who claimed that during the period 1960-1962, the KGB through Romanian Intelligence “succeeded in pilfering hundreds of documents connected in any way with Pope Pius XII out of the Vatican Archives.”[122] Pacepa further asserts that the stolen documents were then used as the basis for the play by Rolf Hochhuth and his Communist producers in order to smear the reputation of the Pope in retaliation for his longstanding opposition to the Communist Party. The veracity of this story was researched by a staunch Pius XII defender, Professor Ronald J. Rychlak of the University of Mississippi. Rychlak, who has written several books and journal articles defending Pacelli, not only confirmed the story by Pacepa but also collaborated with him in writing a book entitled Disinformation (2013) that includes a section on the KGB-Vatican covert operation. Whether the KGB played a role in the production of the play or if Hochhuth is guilty of taking dubious literary license to disparage the reputation of Pius XII, does not exonerate the Pope for remaining “silent” in not raising the public specter against Nazi atrocities. Is it possible that if Pius XII spoke out more forcefully matters could have gotten any worse?

An early influential work on the Pius XII debate is Guenter Lewy’s, The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany (1964). As previously noted, Lewy also comports with the anti-Communist platform of the Holy See as being one of the primary motivations for the Church to embrace the Nazi Party (in the early stages that is) by virtue of a “strong Germany as a bulwark against Russian Communism” but he also notes, “how painstakingly the pope labored at maintaining the Holy See’s posture of neutrality. He did so not only to protect his prospects as a possible mediator but also as the only expedient course of action in a world war that pitted millions of Catholics against each other.”[123] Lewy makes an interesting argument about Pacelli’s desire to maintain Vatican neutrality during the war so as not to jeopardize his prospects of brokering a peace plan; something he was unable to accomplish when he was Nuncio in Germany during World War I. In 2000, the re-issued paperback edition of his book features an updated introduction in which he states that new information on the Pacelli controversy has not changed any of his original arguments:

The Church has responsibility not only for pastoral care and being an organ for salvation but also for making the secular world a better place to live in. It may not remain silent when elementary human rights are violated…This did not happen to a sufficient degree in either Berlin or Rome during the dark days of the Third Reich, and unfortunately none of the many new documents that have come to light since this book was first published in 1964 change this important conclusion.[124]

John S. Conway, one of the first authors to explore the relationship between Nazi Germany and Christianity in his book The Nazi Persecution of the Churches (1968), is extremely influential in laying the groundwork on how both the Catholic and Protestant Churches survived in Germany during the Nazi period 1933-1945. Without specifically naming the Pope, Conway holds both the Church leadership and laity culpable for their complicity with the rise of the Nazi Party, “The Church was unprepared and totally unsuited to cope with the situation, neither the hierarchy nor the laity had the courage or the means to mobilize the Church against the embattled might of Nazism, and thereby to jeopardize the very existence of their own institutions.”[125]

“The Silence of Pius XII” (1979), is also the main criticism of Ethel Mary Tinnemann in her excellent journal article on the topic. She too concludes that the Pope could have done more in speaking out against atrocities:

Since the Pope knew the German determination to annihilate European Jews, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Pius XII had an obligation to speak frankly and decisively to the bishops in 1941 and 1942 and publicly to European Catholics in 1944…Although he had spoken in general terms, as the “defender of truth, justice and charity,” he had an obligation to speak effectively and specifically in this critical period of man’s history.[126]

The policy of Pacelli restraining diplomatic protocol with the Nazis and the Fascists is the subject of a book by John F. Morley, Vatican Diplomacy and the Jews During the Holocaust 1939-1943 released in (1980). What is surprising about this book is not that Morley takes a critical position of Pacelli’s actions but that Morley is also a Catholic priest.

The Vatican’s diplomatic system was such that it could have been an effective means to demonstrate humanitarian concern for all the victims of the war…The Pope, in defining and restraining Vatican diplomatic practice in this way, failed not only Jews but also many members of the Church who suffered brutal treatment from the Germans. Moreover, he caused Vatican diplomacy to fail, by forcing it to make a mockery of its claims that it was an ideal form of diplomacy dedicated to justice, brotherhood, and other similarly exalted goals, when in practice it made little attempt to work toward any of them.[127]

I had the opportunity to speak with Father Morley in July 2016, and he admitted that he did take a rather harsh position on Pacelli in his book but he also noted that since the book’s publication in 1980, new archival material has been released that would need to be further researched in order to determine whether any of his conclusions would need to be modified. Father Morley also faulted the pope for condemning the bombing of Rome by the Allies but said nothing when London was bombed by the Germans.

The authors of Unholy Trinity (1991), Mark Aarons and John Loftus contend that the Pope was responsible for allowing the Church and certain prelates to assist, both financially from Vatican funds and physically through providing false passports “rat-lines” for known Nazi war criminals to escape to South America after the war. “The truth is that the Vatican knew exactly what it was doing at critical points, and adopted policies which led to its own disgrace.” Furthermore, the authors argue that by Pius XII keeping “silent” as to Nazi war crimes, he had moral culpability. “Therein, we submit, lies his guilt; from the moment he assumed St. Peter’s mantle he chose diplomacy over truth, his temporal powers over his moral duty.”[128]

Picking up on this theme of the Pope’s culpability during the Holocaust was the best-selling book by John Cornwell, Hitler’s Pope (1999) in which he contends that Pacelli was not only anti-Semitic but also did little to help the plight of the Jews. In an email response to a question posed to Cornwell regarding whether his view of the Pacelli controversy may have changed since his book was first published in 1999, Cornwell wrote:

If I have altered my views it is to emphasize Pacelli’s role as a Mitläufer, a Fellow Traveler on behalf of Pius XI and the Church, in that he traded benefits with Hitler while disassociating himself from the Nazi ideology… The argument is that those (in the professions, the judiciary, the Churches) who took benefits and did deals with Hitler before the erection of the police state (i.e. in the mid-1930s) did far more damage than they had been actual Nazis: for the effect of being a Mitläufer was to demoralize opposition, scandalize youth, and give credit to Hitler in the eyes of the world.[129]

There is no question that both parties, the Vatican and Hitler, benefited from the signing of the 1933 Concordat. Hitler got the Center Party disbanded and the Holy See was able to obtain certain rights and protections from the Reich that would avoid the persecutions the Church sustained during the Kulturkampf of the late nineteenth century. Unfortunately for the Church, Hitler had no intention of honoring the agreement. While it is true that the actions taken by the Vatican ultimately assisted Hitler’s consolidation of power, could anybody have foreseen in those early years that the Chancellor would plunge the world into war and institute genocide against the Jews? Perhaps a closer reading of Mein Kampf would have been an omen of things to come.

One author who is most vitriolic of both Pius XII and the Catholic Church is Daniel Jonah Goldhagen as evidenced by his book A Moral Reckoning (2002). Goldhagen asserts that Pius should have spoken out about the plight of the Jews because, if he had, it would have saved lives:

Imagine that Pius XII had instructed every bishop and priest across Europe, including in Germany, to declare in 1941 that the Jews are innocent human beings deserving, by divine right, every protection that their countrymen enjoyed and that antisemitism is wrong, and that killing Jews is an unsurpassable transgression and mortal sin, and that any Catholic contributing to their mass murder would be excommunicated.[130]

There is some truth to the allegation that if the Pope had been more forceful with his protests, it might have changed matters. A memorandum dated February 6, 1940 by German Foreign Minister W. Üster reporting on a meeting between Hitler and the Italian Foreign Minister noted how the Pope was able to change Hitler’s attacks on monasteries:

He was watching very attentively the efforts of the Vatican. He was of the opinion that an understanding with the Church was useful. He reminded the Führer of it almost every week. Thus far, however, the Führer had turned a deaf ear to it because of his bad experience with the Vatican. For instance, at the request of the Pope, the Führer had ordered all proceedings against the monasteries quashed.[131]

Dan Kurzman in A Special Mission (2007) recounts the plan by Adolf Hitler to have the German occupying forces in Rome in September 1943 kidnap the Pope and bring him to Germany reminiscent of what Napoleon did in 1808. Kurzman asserts that since the Pope was aware of this danger, he remained “silent” so as not to jeopardize himself or the Church treasures contained in the Vatican Museum. However, even with this danger lurking outside the Vatican walls, Kurzman argues that the Pope should have still spoken publically about the plight of the Jews, “At least for genocide, did not morality trump realism as a sacred value and require him to speak out publicly at any cost?[132]

Mary Chang (2009) admires the Pope for his courageous position that he stood for during the Holocaust, “Under these treacherous circumstances, Pope Pius XII showed an unusual courage and willingness, to use his authority for world peace, and played an important role in Opposition history.”[133]

Hubert Wolf also weighs in on this concept of diplomacy over doctrine in his book Pope and Devil (2010). Here, he takes a dim view of Pacelli’s diplomatic philosophy as Cardinal Secretary of State:

In his advocacy of the primacy of politics over the purity of doctrine, Pacelli had gone to the limits of the possible. He had in a particularly adroit manner managed to attenuate a magisterial instruction from the Holy Office in the interests of his concordat politics. With all his rhetoric of humility and flowery submissiveness, he always remained focused on his political maneuverability as a diplomat of the Holy See in Germany. The arguments of opportunity that he used show clearly that he place diplomacy ahead of dogma.[134]

In his book The Pope and Mussolini (2014), David I. Kertzer concentrates most of his research during the rise of Fascism in Italy in the early 1920s and through the Pontificate of Pius XI. While Pacelli was not Pope at the time, Kertzer does hold him accountable for many of his actions as Cardinal Secretary including: suppressing controversial documents, tempering the tone of newspaper reports issued from Catholic organizations, and insuring that certain inflammatory statements from Pius XI regarding foreign policy matters were properly censored before release:

That the Duce and his minions counted on the men around the pope to keep Pius XI’s increasing doubts about Mussolini and Hitler under control is a story embarrassing for a multitude of reasons, not least the fact that the central player in these efforts was Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, the man who would succeed Pius XI.[135]

The moral dilemma facing the Catholic Church during the 1930s and the war years was how to deal with the growing violence toward German Catholics and Jews in the occupied territories? In Church of Spies (2015), Mark Riebling correctly notes this dual role of the Pontiff: “The pope did not have one role, but two. He had to render to God what was God’s, and keep Caesar at bay…He merely encompassed, in compressed form, the existential problem of the Church: how to be a spiritual institution in a physical and highly political world.”[136]

Conclusion

The documents released from the Vatican archives in 2003 and 2006 confirm some of the critical roles that Eugenio Pacelli played in the nearly six decades of his ecclesiastical and diplomatic career until his death in 1958. During that time, he participated in the drama of two world wars, the Holocaust, the reconstruction of Europe, and stood as a stalwart in the fight against the spread of world Communism during the cold war. Pacelli, who outlived Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Franklin Roosevelt, and Joseph Stalin, was one of the towering figures of the Twentieth Century. It is important to note that Pius XII was not only the spiritual leader of millions of Catholics around the world but also the Pontiff of the Holy See, a powerful political sovereign state that required astute diplomatic strategies in dealing with belligerents during a time of war.

In the final analysis, the essential critique by many scholars and writers is that Pius XII, as Vicar of Christ, should have publicly denounced the atrocities perpetrated against the Jews by the Nazis during World War II. Instead, he chose to be “silent.” What is unknown is whether his silence was attributable to his involvement with the German Resistance, his desire for the Vatican to remain neutral, or his fear that speaking out publically against the Nazis would jeopardize the lives of Jews and Catholics alike.

As the war dragged on into 1943, the Nazi war machine began suffering major military defeats on both Fronts. The Wehrmacht was in retreat in Russia, Italy, and in France after D-Day in June 1944 and Allied bombing raids in Hamburg, Berlin and later Dresden were having devastating effects on the German civilian population. For all intents and purposes, the war was over but Hitler would not relent. Ian Kershaw notes that after the Valkyrie assassination attempt, Hitler was deluded into thinking that the military losses were attributable to his generals sabotaging the war effort, “Now I know why all my great plans in Russia had to fail in recent years,” he ranted, “It was all treason! But for those traitors, we would have won long ago.”[137] The subsequent purge of those considered to be “traitors” was an indication of the volatile mental state of the Führer. Hitler was becoming more deranged and more dangerous as the war raged on. It is, therefore, not unreasonable to suspect that Pius XII had every reason to fear severe retaliation both to Jews and Catholics if he openly criticized Hitler and the Nazi genocide of the Jews, especially while the Nazis occupied Rome in 1943-1944.

Despite these concerns, Pius XII was not afraid to assist the German Resistance when asked to participate in plans to overthrow Hitler nor did he waver when German forces occupied Rome and Jews were hidden in monasteries and convents.

In the aftermath of World War II and the Holocaust, one can easily question the motivation behind the Catholic Church negotiating a Concordat with the Nazi Party, but during the first year of the Third Reich (1933) under Adolf Hitler, Pius XI and his Cardinal Secretary of State Pacelli were apparently naively misled into thinking that Hitler would be a partner with the Church in standing up to the threat of atheistic Bolshevism. While Hitler was indeed intent on destroying Bolshevism, he was also intent on destroying the Jews and deconstructing the Catholic Church into an organization useful to the Nazi Party.

It is easy to criticize the acts of important political and religious figures from the safe distance of historical perspective but to actually live through the events and be called upon to make decisions that impact the lives of millions of people is a daunting task. Few will ever experience what Pacelli lived through. Like all men, to err is human but Eugenio Pacelli should be admired for exhibiting the rare gift of maintaining composure under extreme duress. When called upon to speak out, he did not succumb to the pressures of others but followed his own inner voice and guidance as he felt led by the Lord. Pacelli’s hatred of Bolshevism may have blinded him to the reality that giving even tacit support to the Nazis in their fight to crush world Communism may have cost the lives of countless Jews by not speaking out.

In the not too distant future, a sitting pope will authorize the opening of the post-1939 secret archives and allow scholars to fully research the tumultuous period in which Eugenio Pacelli presided over the world’s largest church. Frank J. Coppa believes that over the past half century sufficient evidence and archival records have already been made available to assess the papacy of Pius XII, “Unfortunately, both advocates and adversaries have explored these volumes selectively, often only to support their pre-established positions on religious, ideological, political, and psychological considerations, transcending the thought and policies of Pius XII.”[138]

While Coppa may be a bit cynical about the integrity of some historians, the fact remains that new archival evidence will only broaden our understanding of how Pius XII conducted the Papacy and perhaps definitively answer the question why he remained silent.

In a fitting memoir entry from 1942, Harold Tittman, Jr. predicted the coming Pacelli controversy for generations to come:

But Pope Pius XII never did speak out while the war was in progress, so there is no evidence from which to judge whether it was the right thing to do or not. If he had spoken out, would there have been fewer victims or more? There can be no final answer. Personally, I cannot help but feel that the Holy Father chose the better path by not speaking out and thereby saved many lives.[139]

Epilogue

The existence of the secret encyclical on race, Humani Generis Unitas, written by John La Farge, Gustav Gundlach, and Gustave Desbuquoise in 1938 was unknown to the outside world until an article written by Jim Castelli on Pope Pius XII appeared in the National Catholic Reporter[140] in 1972 claiming that the concealed document was filed away somewhere in the labyrinth of the Vatican archives. A Benedictine monk and former member of the anti-Fascist Resistance movement named Georges Passelecq read the article and invited Jewish historian Bernard Suchecky to join him on a quest to locate a copy of the secret draft encyclical. After being told on three different occasions that the Vatican archives had no record of the document, a former Jesuit history professor at Florida International University named Thomas Breslin heard about their search and in 1987 provided them with a copy of the document written in French that he photographed while cataloguing the papers of John La Farge.[141] Later in 1994, the pair obtained a German version of the same encyclical corroborating the French text. Passelecq and Suchecky then published the first English translation of the encyclical as part of a book entitled The Hidden Encyclical of Pius XI (1997).

As expected, the draft encyclical was clear in its condemnation of Nazi and Fascist anti-Semitism:

Thus we find that anti-Semitism becomes an excuse for attacking the sacred Person of the Saviour Himself, who assumed human flesh as the Son of a Jewish maiden; it becomes a war against Christianity, its teachings, practices, and institutions. Anti-Semitism attempts to embarrass the Church by giving her the alternative either to join with the anti-Semites in their total repudiation of any esteem or regard for anything Jewish, and thereby to associate herself with the anti-Semites in their campaigns of vilification and hatred; or else to embarrass the Church by involving her in the machinations and struggles of profane politics, attributing earthly and political motives to her legitimate defence of the Christian principles of justice and humanity.[142]

The encyclical also indicted the Nazis for the persecution of the Jews:

As a result of such persecution, millions of persons are deprived of the most elementary rights and privileges of citizens in the very land of their birth. Denied legal protection against violence and robbery, exposed to every form of insult and public degradation, innocent persons are treated as criminals though they have scrupulously obeyed the law of their native land.[143]

The original draft of the encyclical was completed during the summer of 1938 but was not submitted directly to Pope Pius XI. Instead, it went to his close advisor, Wlodimir Ledóchowski, the head of the Jesuit Order and La Farge’s direct superior. Ledóchowski read the text and deemed it too inflammatory to submit to the Pope so he passed it on to fellow Jesuit Enrico Rosa for editing. The encyclical sat dormant for months because Rosa was battling a grave illness and died in November 1939. Meanwhile, Gundlach suspected foul play by Ledóchowski for purposely not presenting the draft directly to Pius XI because of his rabid anti-Communist world-view and support for the Nazi Party’s strong opposition of Bolshevism. Exasperated at the impasse, Gundlach admonished La Farge to bypass Ledochowski and submit the encyclical directly to the Pope. Finally in January 1939, the Pope resolved the issue by demanding that the draft encyclical be sent to his office immediately. Apparently, Pius XI wanted to incorporate portions of the text into his upcoming Lateran speech. It is unknown at what stage the Pontiff was at in reviewing the encyclical but unfortunately for La Farge and his co-authors, the Pope died in February 1939 and the encyclical was never released to its intended audience. Shortly after Pius XII became Pontiff, the encyclical was returned to La Farge and his co-authors and told that they could release the document but only under their own names and subject to Vatican censors. The authors decided against the publication of the document and it was filed away until it re-surfaced in 1972. [144]

On August 12, 1950, Pius XII issued his own version of Humani Generis. Unlike the secret encyclical prepared in 1938, this new Humani Generis was instead a refutation of current philosophies that were contrary to established Church doctrine. The subtitle of the encyclical explains its intended purpose:

Encyclical of Pope Pius XII Concerning Some False Opinions Threatening To Undermine The Foundations of Catholic Doctrine.

The text contains no mention of anti-Semitism or Jewish persecution during the Holocaust period. Not surprisingly, the Pope who always condemned Bolshevism throughout his ecclesiastical ministry, does single out “Communists”[145] as the chief advocates for “false opinions.”

### End Part IV ###

References

[92] Kevin Madigan, “A Survey of Jewish Reaction to the Vatican Statement on the Holocaust,” Crosscurrents, (Winter 2000/2001), 495. [93] Madigan, “A Survey of Jewish Reaction to the Vatican Statement on the Holocaust,” 496. [94] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polish_census_of_1931. [95] Conway, The Nazi Persecution of the Churches 1933-194, 239. [96] Pope Pius XII, Summi Pontificatus, Article 106, October 20, 1939, http://www.papalencyclicals.net/Pius12/P12SUMMI.HTM. [97] Frederick Brown, “The Hidden Encyclical,” The New Republic Vol. 214 No. 6 (April 15, 1996), 27. [98] Goldhagen, A Moral Reckoning, 40-41. [99] Conway, The Nazi Persecution of the Churches 1933-1945, 243. [100] August Cardinal Hlond to Luigi Cardinal Maglione, 19 March 1941, as quoted by Ethel Mary Tinnemann, “The Silence of Pope Pius XII, “267. [101] Adam Sapieha to Luigi Cardinal Maglione, 3 November 1941, as quoted by Ethel Mary Tinnemann, “The Silence of Pope Pius XII, “267. [102] Letter from Myron C. Taylor to Cardinal Luigi Maglione, September 26, 1942, http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/taylorlet.html. [103] Mark Biondich, “Religion and Nation in Wartime Croatia: Reflections on the Ustaša Policy of Forced Religious Conversions, 1941-1942.” The Slavonic and Eastern European Review Vol. 83 No.1 (Jan. 2005), Footnote 4. 72. [104] Emily Greble Balić, “When Croatia Needes Serbs: Nationalism and Genocide in Sarajevo, 1941-1942,” Slavic Review Vol. 68 No. 1 (Spring 2009), 128. [105] Documents on German Foreign Policy, Series D. Volume XIII, No. 90. https://archive.org/stream/DocumentsOnGermanGoreignPolicySeriesDVolumeXiii/DocumentsOnGermanForeignPolicySeriesDVolumeXiiiJune23-December111941#page/n106/mode/1up/search/croatia [106] Julia Gorin, “Mass Grave of History: Vatican’s WWII Identity Crises,” The Jerusalem Post ( February 22, 2010), http://www.jpost.com/printarticle.apx?id=169378. [107] “The Case of Archbishop Stepinac,” Published by the Embassy of the Federal Peoples Republic of Yugoslavia Washington, 1947. http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/62/123.html. [108] John F. Morley, Vatican Diplomacy and the Jews During the Holocaust 1939-1943 ( New York: KTAV Publishing House Inc.1980), 164-165. [109] Alperin vs. Vatican Bank, http://cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/memoranda/2009/12/29/08-16060.pdf. [110] Lewy, The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany, 250. [111] Tittman Jr., Inside the Vatican of Pius XII: The Memoirs of an American Diplomat During World War II, 166. [112] Letter from Pope Pius XII to Franklin Roosevelt, July 20, 1943. http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/PSF/BOX52/t468q01.html. [113] Kertzer, The Pope and Mussolini, 390-391. [114] Fifth Installment – Diaries of Joseph Goebbels, “Goebbels Opposed ‘Attack’ on Vatican, “The New York Times (May 19, 1948), 12. [115] McGoldrick, “New Perspectives on Pius XII,”1035. [116] McGoldrick, “New Perspectives on Pius XII,”1035. [117] Kurzman, A Special Mission: Hitler’s Secret Plot to Seize the Vatican and Kidnap Pope Pius XII, 142. [118] Kurzman, A Special Mission, 134. [119] Riebling, Church of Spies, 185. [120] Mark Aarons and John Loftus, Unholy Trinity: The Vatican, the Nazis, and the Swiss Banks, (New York: St. Martin’s Press ,1991), 33. [121] Aarons and Loftus, Unholy Trinity, 25-27. [122] Ion Mihai Pacepa, “Moscow’s Assault on the Vatican,” The National Review (Jan 25, 2007). Online version http://www.nationalreview.com/node/219739/print. [123] Lewy, The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany, xix. [124] Lewy, The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany, xxvii. [125] Conway, The Nazi Persecution of the Churches 1933-1945, 331. [126] Tinnemann, “The Silence of Pope Pius XII,” 285. [127] Morley, Vatican Diplomacy and the Jews During the Holocaust 1939-1943, 209. [128] Aarons and Loftus, Unholy Trinity, 264, 287. [129] John Cornwell, email response to question posed by Gary DeGregorio, June 19, 2016. [130] Goldhagen, A Moral Reckoning, 55. [131] Documents on German Foreign Policy. #596, “Memorandum by an Official of the Embassy in Italy,” Feb 6, 1940. [132] Kurzman, A Special Mission, 240. [133] Chang, “The Vatican and the German Resistance,” 398. [134] Wolf, Pope and Devil, 245. [135] Kertzer, The Pope and Mussolini, 405-406. [136] Riebling, Church of Spies, 25. [137] Kershaw, Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis, 687. [138] Coppa, “Between Morality and Diplomacy, 567-568. [139] Tittman Jr., Inside the Vatican of Pius XII, 122-123. [140] Jim Castelli, “Unpublished Encyclical Attacked Anti-Semitism,” National Catholic Reporter, (December 15, 1972), 8. [141] Frederick Brown, “The Hidden Encyclical,” The New Republic (Apr. 15, 1996), 30. [142] J. La Farge, G. Gundlach, G. Desbuquoise, “Humani Generis Unitas,” Article 147. http://www.ccjr.us/dialogika-resources/primary-texts-from-the-history-of-the-relationship/1254-hgu1938. [143] “Humani Generis Unitas,” Article 132. [144] Brown, “The Hidden Encyclical,” 30. [145] Pope Pius XII, “Humani Generis,” Article 5, August 12, 1950. http://www.papalencyclicals.net/Pius12/P12HUMAN.HTM