Giving thanks is a fundamental practice in Christianity, including the Catholic Church, and other religions. Ecumenical expressions of gratitude characterize American history. They include the legendary autumn feast held by the Pilgrim settlers in the Massachusetts Bay area in 1621, to celebrate their survival for one year in their new home. They warmly welcomed Native Americans who had helped them survive. In 1789, President George Washington issued the first national Thanksgiving proclamation.

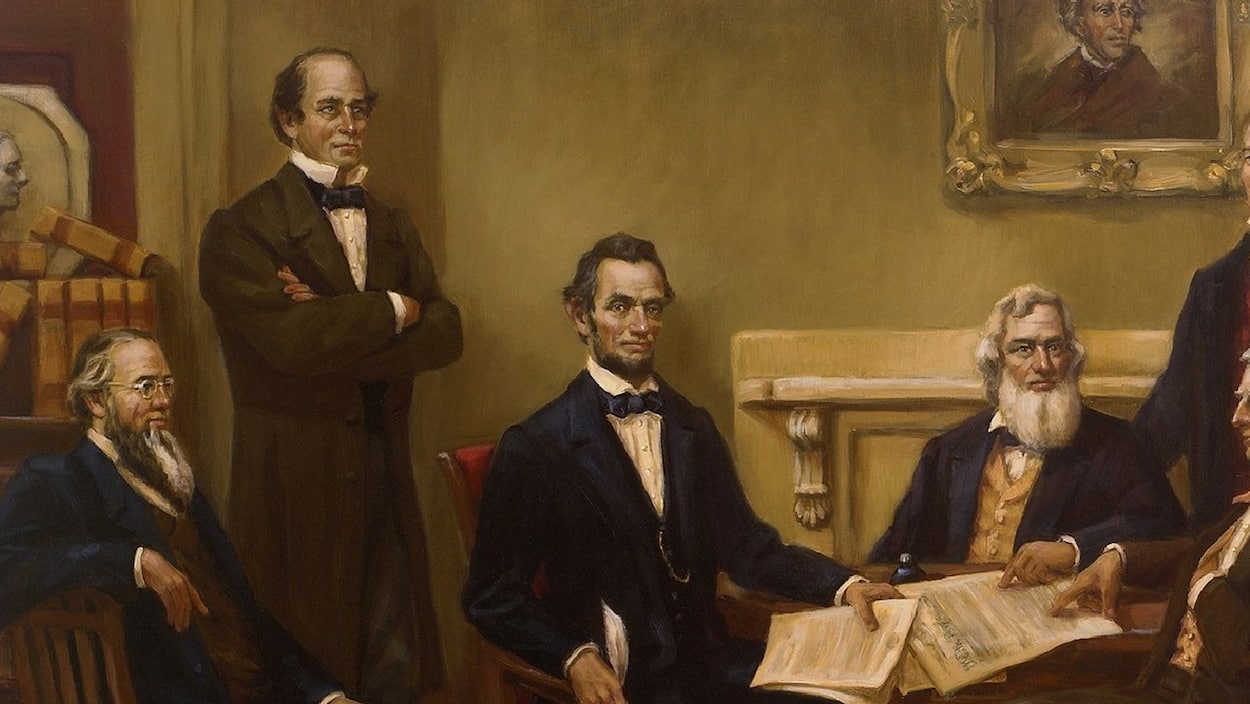

Thanksgiving effectively for us means inclusion. President Abraham Lincoln made that point profoundly during our Civil War. On October 3, 1863, the White House issued the Thanksgiving Proclamation, which declared the last Thursday of November to be a “day of thanksgiving and praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.” He also humbly requested “the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore … peace, harmony, and Union.”

Earlier, Lincoln had ordered government offices closed on November 28, 1861 for a day of thanksgiving. Up until the 1863 proclamation, individual states had celebrated days of giving thanks. Sarah Joseph Hale, editor of the influential Godey’s Lady’s Book, had written to Lincoln in late September of that year pressing for a national day of thanks, a goal she pursued for many years without success. According to John Nicolay, Lincoln’s administrative aide, Secretary of State William H. Seward signed the document. Lincoln and Seward by then were friends as well as colleagues.

Unity was an overarching Lincoln theme throughout the Civil War, employed with shrewd calculation and brilliant political timing. By the fall of 1863, the strategic position of the Union had taken a marked turn for the better. In July, there were two significant victories – the Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania and the capture of Vicksburg Mississippi. A sizable Confederate army never again would invade the North, and the great Mississippi River was now completely in Union control.

During the preceding year, one military development provided Lincoln with political opportunity. On September 17, 1862, the Army of the Potomac under General George B. McClellan defeated General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Antietam Creek in Maryland. The victory was technical, in that Lee withdrew and left the Union forces in control. Nevertheless, the outcome qualified as a Union military success, desperately welcome after more than a year of defeats and inconclusive engagements in the East.

Lincoln faced extremely serious challenges beyond the Confederacy. General McClellan was a popular commander with rank-and -file soldiers and someone with national political ambitions of his own. He was committed to the Union but also opposed abolition of slavery. A talented organizer and administrator, he refused to be aggressive in attacking Lee’s army.

McClellan was insubordinate to President Lincoln, demanding control over all war policy. In speaking with Lincoln, McClellan implied strongly that the military might refuse to follow the president’s orders. By the second year of the war, Lincoln had had enough, and the failure to follow up the victory at Antietam provided justification to act. He fired McClellan, who became the Democratic Party’s 1864 presidential nominee to oppose Lincoln at the ballot box, again unsuccessfully.

Having secured control over the Union Army of the Potomac, President Lincoln moved quickly to exploit the Antietam victory by issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. The executive order, issued on January 1, 1863, declared free slaves held in the Confederate states. Beginning in the fall of 1862, the U.S. government issued a series of warnings under the Second Confiscation Act, passed by Congress on July 17, 1862. The legislation confirmed in law Lincoln’s authority to use his War Powers to seize Confederate property and impose other penalties. Technically, slaves in the South qualified as Confederate “property.” Adding the end of slavery explicitly to Union war goals greatly diminished ominous support in both Britain and France for recognizing the Confederacy.

Critics have argued Lincoln should have used emancipation comprehensively, to include states that remained in the Union, but that would have been illegal and unwise. Slavery was still legal under the Constitution, and ended in law only when a sufficient number of states ratified the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution on December 18, 1865, months after the end of the Civil War. Additionally, many people still in the Union, including in particular the Border States, supported slavery.

By design, the Emancipation Proclamation is a detailed dry legal brief. The document makes the case for removing property from those in rebellion, with emphasis on particulars of procedure. There is no reference to fundamental moral concerns. Gripping soaring prose makes Lincoln’s greatest speeches inspiring – the Gettysburg Address and Second Inaugural are vivid examples. In the Emancipation Proclamation, we see Lincoln the skilled lawyer, and disciplined insightful strategist.

Immediately, the Civil War transformed from a struggle focused on preservation of the Union to one that included abolition of slavery. Lincoln from his youth intensely hated slavery. He fully aligned in sentiment with the abolitionists and the Radical Republicans, but he avoided their extreme tactics and rhetoric. Lincoln regularly praised the people of the South. After one such speech, a woman of powerful pro-Union views approached and denounced him in bitter terms. Lincoln calmed her by saying, “Madam, do I not destroy an enemy if I make him a friend?”

A test for us as Christians is our effectiveness as well as determination in putting sentiments into action. Lincoln’s sustained implementation of realistic, effective strategy during the Civil War is a particularly important example of faith in action.

The struggle for equality of treatment for African-Americans has continued since the Civil War. A century later, the decade of the 1960’s was especially important with both racial violence and important progress. The massive March on Washington on August 29, 1963 was a turning point, leading to the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965 signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is a major enduring civil rights leader, consistently advocating nonviolence and honored today while more extreme and violent figures of that era have faded. His political shrewdness reflects Lincoln’s own. The Catholic Church has provided sustained leadership for civil rights.