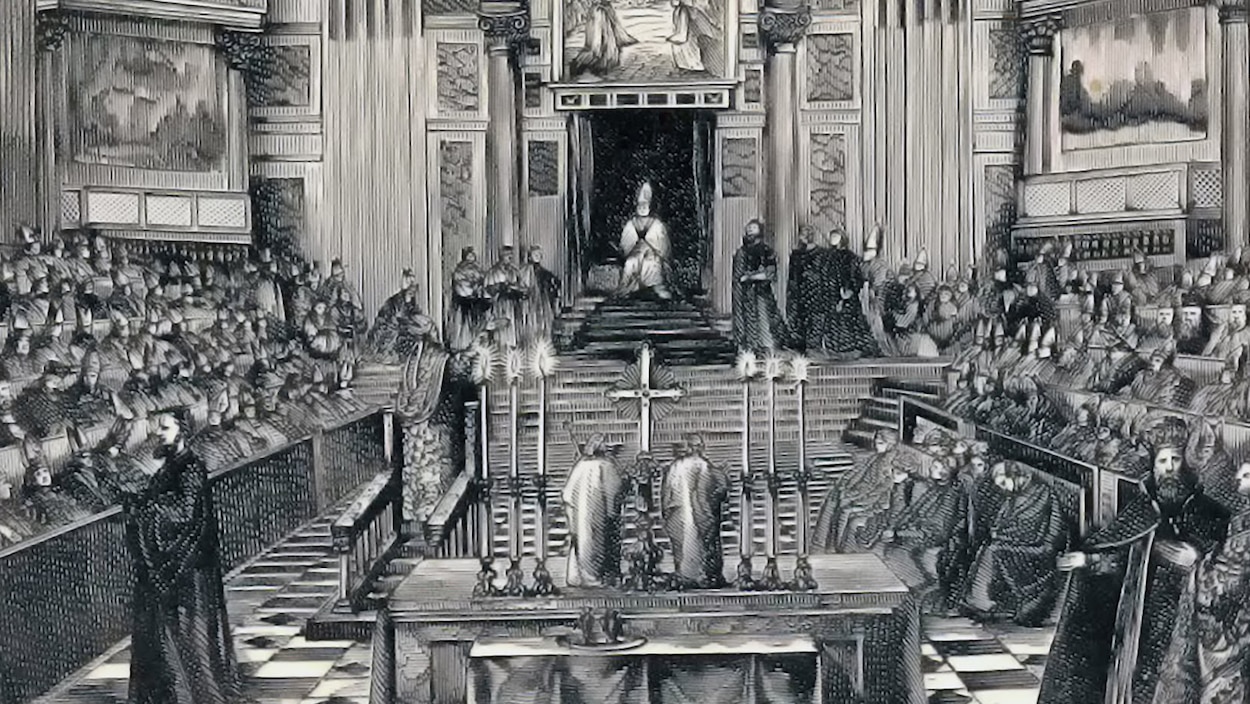

Part 1 discussed the origin of the doctrine of Papal Infallibility in the first Vatican Council (1869-1870). Part 2 examined the intellectual climate at that time, the theological differences, and their impact. Part 3 considered the confusion that still exists about the doctrine and Pope Francis’ agreement to “an open and impartial discussion on the matter” with Hans Küng, who calls the issue a “key question of destiny” for the Church. Now, Part 4 explores the possibility of changing the doctrine.

Given the confusion about the doctrine of infallibility that still exists, the possibility of an open discussion about it excites Catholics and non-Catholics around the world. It is natural, therefore, to consider the questions that are most relevant and the answers that supporters and critics of the doctrine might give. Because the supporting arguments are much better known than opposing arguments, I will only state the former but state and explain the latter. (Note: I am not suggesting that Pope Francis or Professor Küng would make any of these arguments.)

Is it possible for the Church to change or overturn the doctrine of infallibility?

The Magisterium answers “no” because (a) an infallible doctrine by definition cannot be changed, let alone overturned; and (b) the Church has never changed its teachings on important issues.

One opposing answer is that “a” is invalid because the doctrine being evaluated cannot logically be used to prove itself. Another is that “b” is not factual—the Church has changed its teaching on important issues. Here are some examples of significant change:

The sale of indulgences. Three popes (Leo X, Nicholas V, and Julius II) approved the practice in the building of St. Peters Basilica. After the Reformation the practice was banned by the Church.

Usury. The Church long forbade charging any interest for lending money. Later the prohibition was revised to lending at “excessive” interest. Today the term “usury” does not even appear in the Catechism.

Slave-owning. A number of Popes regarded slave-owning as permissible, notably Nicholas V. Over four centuries later, Leo XIII condemned it.

Torture. Heretics were long permitted to be tortured for their beliefs; today religious liberty is affirmed and torture condemned.

The case of Galileo. At Pope Paul V’s direction, Galileo was ordered “to abandon completely. . . the opinion that the sun stands still at the center of the world and the earth moves, and henceforth not to hold, teach, or defend it in any way whatever, either orally or in writing.” Later the Inquisition charged him with being “vehemently suspect of heresy,” demanded that he “abjure, curse and detest” his views, and placed him under house arrest, which continued until his death. On October 31, 1992, more than 350 years after Galileo’s condemnation, Pope John Paul II apologized for the Church’s role in the affair. (Incidentally, John Paul offered 100 such apologies during his papacy.)

It might be objected that in some of these cases, the Magisterium has never formally changed Church teaching. That objection, a common one, is based on the belief that only formal pronouncements count as real changes; in other words, if the Church tacitly approves an act for centuries but then suddenly condemns it as a sin, nothing has really changed. That is refuted by the fact that the act at first did not have to be mentioned in the confessional, and then it did! (The reverse happened in the case of usury. No formal pronouncement was ever made, but the definition of usury was changed from: “any lending of money for interest” to “lending of money for excessive interest.” Today’s Catechism does not mention usury.)

Even so, aren’t the changes cited above very different and less serious than any change in infallibility doctrine would be?

The Magisterium replies yes, that is precisely the point. In all the cases cited, the Magisterial statements were not formal judgments of “faith and morals” made ex cathedra, but instead the personal opinions of one or more individuals; therefore, the cases do not challenge the doctrine of infallibility.

The opposing answer is that Popes and bishops are not, and have never been, just regular folks whose personal views have no larger dimension. Rather, they are successors to the apostles of our Lord and Savior, so whatever they say is understandably (if sometimes incorrectly) regarded as inspired by the Holy Spirit. In fact, the number of hierarchical statements demanding assent of mind and will has been sufficient to create the impression that everythingthe hierarchy says must be accepted without question.

To appreciate the impact of such “personal opinions” on people’s lives, consider the tens of thousands of people who were misled into believing that giving a substantial portion of their income and property would earn them a free pass to heaven. Think, too, of the millions who were prevented from earning reasonable interest on their money for fear of committing the mortal sin of usury, as well as those who were allowed to believe it is morally acceptable to enslave fellow human beings and practice torture. That the Magisterium now holds views of these matters completely opposite from its original views does not erase the harm done by the original views. Nor does describing the original views as mere “personal opinions” increase confidence in other, more formal magisterial judgments.

Another answer to the magisterial argument concerns the specification that infallible pronouncements concern “faith and morals.” (Morals, of course, refer to matters of right or wrong behavior.) The sale of indulgences, usury, slave owning, and torture were moral matters, and major ones at that. The idea that some of the Church’s moral teachings are fallible and wrong whereas others are infallible raises difficult questions: Is the Holy Spirit’s guidance in moral matters selective or sporadic? Or is that guidance constant but the grasp of it by popes and bishops sometimes flawed? If the latter, what will prevent the Magisterium from making a wrong judgment about a serious moral matter next year, then misperceive it to be infallible and for decades, centuries, or millennia require the laity to give it assent of their minds and wills?

An even more relevant reply to the assertion that the Magisterium has never formally changed Church teaching is this: The Magisterium itself has already changed the doctrine of infallibility! To be more specific, it has expanded infallibility beyond “the pope only, speaking ex cathedra” to include definitive Magisterial statements made by bishops, even though they are not made ex cathedra.

Have the consequences of the doctrine of infallibility been so negative as to warrant considering its change or retraction?

The Magisterium’s answer is that the only negative consequence of the doctrine of infallibility has been the opposition of a vocal minority of bishops and theologians. The Magisterium argues further that the doctrine should not be changed: first, because changing it would mean that the most prominent pronouncement in modern Catholic history was wrong; and secondly, because no explanation, however artfully constructed, could soften the fact that every pope since Pius IX, who convened Vatican I—eleven of them in all—at least tacitly supported the infallibility doctrine. The reaction to these ideas would be mass disillusionment among priests, religious, and laity alike, and over time mass exodus from the Catholic Church.

The opposing answer acknowledges that changing a doctrine that has come to be a hallmark of Catholicism, one that sets it apart from all other religions, would have significant consequences. But it adds that the consequences that have occurred over the last 150 years have not been as salutary as the Magisterium implies. Here are some of those consequences:

1) By fostering an intellectual climate that emphasized obedience to papal authority and discouraged dissent, the doctrine of infallibility intimidated theologians and diminished, in some cases silenced, their scholarly inquiry. It also created pressure on future popes (and bishops) to maintain, and even expand, authoritarian governance of the Church. The record of Vatican Council II’s proceedings, a century later, offers evidence of such pressure, particularly in the rejection of the case for contraception. (Note: although unquestioning obedience was arguably understandable in 1870 when the average European received between 3 and 4.5 years of schooling and the average American 6 years, it has grown less so as the average years rose to 8 years, 12 years, and higher.)

2) The stronger emphasis on unquestioning obedience, together with the continuation of the Index of Forbidden Books (which continued in force until 1966) increased Catholics’ fear of intellectual and spiritual contamination by the thoughts of non-Catholic writers. That fear was arguably a significant factor in the low intellectual achievement of Catholic education, a deficiency noted by Richard Hofstadter in Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1966): “[Catholicism] has failed to develop an intellectual tradition in America or to produce its own class of intellectuals capable either of exercising authority among Catholics or of mediating between the Catholic mind and the secular or Protestant mind.” He cited, among other sources, Bishop John L. Spalding’s 1884 description of Catholic seminaries as “not school[s] of intellectual culture, either here in America or elsewhere, and to imagine that [they] can become the instrument of intellectual culture is to cherish a delusion”; also, almost 70 years later (1952), researcher Robert H. Knapp’s conclusion that “the record of Catholic institutions [in general] was exceptionally unproductive in all areas of scholarship,” and notably in the humanities.

3) The deficiency Hofstadter described was surely a factor in the intellectual unpreparedness of Catholics for the social revolution of the 1960s, which contrary to popular notion was not driven as much by hippies at Woodstock as by the Humanistic Psychology of Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow. The Church failed to recognize the danger of that psychology—in fact, regarded it as “friendly” to Catholicism—and opened the doors of convents, abbeys, rectories, and colleges to its purveyors. Ironically, those doors were opened at the same time the Vatican II was “opening the windows” to the outside world. (See my book Corrupted Culture for a detailed discussion of this phenomenon.)

4) Because many Catholic priests, nuns, and lay people were intellectually unprepared to evaluate the claims of Humanistic Psychology, many priests and nuns set aside both their vows and their moral restraints, “followed their feelings,” and explored new “lifestyles.” Many in the laity treated their marriage vows similarly. Incidentally, it is a mistake to say that the sexual revolution was primarily a result of the “birth control mentality.” It was, instead, a result of uncritically embracing the claims of Carl Rogers, Abraham Maslow, and Alfred Kinsey that all forms of sexual expression are wholesome and suppression of any desire, no matter how aberrant, is psychologically damaging.

5) Because they were conditioned to be suspicious of any secular thought that might conceivably undermine their obedience to Church teachings, Catholics were inclined to be hesitant to endorse educational initiatives that stressed skill in logic, critical thinking, problem solving, and decision-making. The most significant of those initiatives included the Great Books program, the Paideia Proposal, and the Critical Thinking movement begun in the early twentieth century and renewed in the 1970s and 1980s. Catholics’ hesitancy was lamentable not only because those movements were a natural fit with the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas, but also because they advocated reason over emotion and objectivity over subjectivity and thus were an effective counter to the premises and promises of Humanistic Psychology.

To say that all or even most of the most significant problems the Church has experienced over the last century or so were caused by the doctrine of papal infallibility would oversimplify a complex matter. On the other hand, it would be equally irresponsible to deny that there was a “qualitative correspondence” or significant correlation between the Church’s suppression of independent thought and Catholics’ subsequent susceptibility to fallacies.

What action, then, should the Church consider taking regarding the doctrine of infallibility?

This question brings to mind the axiom, “fools rush in where angels fear to tread,” written, appropriately enough, by Alexander Pope. To recommend any action in such a sensitive matter as the doctrine on infallibility would invite condemnation from one side of the issue or the other, perhaps both sides. On the other hand, to speak about change without specifying its form would render discussion meaningless. Given what has been written so far in this essay, an action worthy of consideration would be a formal statement by the Magisterium that includes the following seven components:

1) Affirmation of each belief contained in the Apostle’s Creed. 2) Affirmation of traditional Catholic teaching that because human nature is “fallen,” intellect “clouded,” and will “weakened,” all humans are subject to error. 3) Affirmation that the Holy Spirit offers guidance toward truth, but humans are capable of misunderstanding or resisting that guidance, particularly when they lack humility. 4) Admission that though Popes and bishops have been guided to great insights over the centuries, like their fellow human beings they have also made errors, some of which have lamentably been included in Catholic teaching and have done harm. 5) Admission that, in light of the evidence of the 150 years since it was pronounced, the doctrine of papal (or magisterial) infallibility is understood to be in error. 6) A humble and sincere request for the forgiveness of all that this doctrine has touched, including both those who gave it their assent and those who could not in conscience do so and suffered for their independence of mind. 7) A request for the prayers of all Catholics that the hierarchy will serve God and their fellow Christians wisely and well.

Would such a change be better or worse for the Church?

The Magisterium’s answer is that such a change would be worse for the Church because, as written, the change does not modify the doctrine but retracts it and no explanation of that retraction, no matter how artfully constructed, could soften the stark message that the most prominent pronouncement in modern Catholic history was wrong! Moreover, that all eleven of the popes since Pius IX who supported it were in error. The reaction to any such message would be mass disillusionment among priests, religious, and laity alike, and in time a mass exodus of Catholics from the Church. Those who remained would be in a continuing state of confusion and/or doubt because there would be no end to the questions about other Catholic teachings, and no priest, bishop or pope would be trusted to answer them. Accordingly, false teachings would go unchallenged.

Those who oppose the infallibility doctrine reply: Yes, such a change would be a retraction, but with such an absolute doctrine, no lesser change is possible. And yes, for many Catholics (though surely not all, perhaps not even most) there would be disillusionment, confusion, and loss of trust, but these would give way to a more positive view. At first there would be a deep sense of loss: “The Church is not what I have always believed it to be.” Then anger: “They deceived me, deliberately unveiled a doctrine they knew to be false and made me feel protected by its certitude.” But, in time, a more Christian reaction: “They meant to discern the Holy Spirit’s will, but their human imperfection, the same imperfection we all bear, thwarted their efforts. What is more important, however, is that they have humbled themselves, acknowledged their error, and asked for the forgiveness that we are all required to give, ‘not seven times but seventy times seven.’” Then, finally, an act of faith: ‘We still have the Father, the Son, the Holy Spirit, the Church, and the Creed. Only a single doctrine is gone, infallibility, and that has been more a source of disharmony and dissension than an aid in the pursuit of truth.”

The Church would still have the hierarchy, and in most respects they would be the same as before, only more humble and more aware of the need to remain so by remembering their fallibility. Among the blessings that would flow from that humility would be greater openness to the guidance of the Holy Spirit toward discernment and thus greater effectiveness in combatting Relativism, Selfism and any other false doctrines that may arise in the future. (See Proverbs 11:2)

It may be likely that such a change in doctrine would cause a number of Catholics to leave the Church, but it is no less likely that a majority would remain, many who have left would return, and some people of other faiths or no faith would be drawn closer to Catholicism. After all, a display of genuine humility, particularly from those in positions of great authority, has a way of evoking respect and admiration from all who witness it. (See Matthew 23:12)

May the Holy Spirit’s guidance be perceived ever more clearly by the Magisterium and by all who love Christ.

Copyright © 2018 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved