It is painfully obvious that America has fallen off its cultural path and is at war with itself over a multitude of issues. The author of the new book Why Liberalism Failed, Patrick Deneen has brilliantly exposed the historical roots of this historic situation. As one reviewer put it, Deneen offers an astringent warning that the centripetal forces now at work on our political culture are not superficial flaws but inherent features of a system whose success is generating its own failure. Deneen’s views are however not new.

He echoes a major theme of Russell Kirk’s provocative book of essays, Beyond the Dreams of Avarice, that the walls of Jericho fell down, not because the trumpet blast was strong but because the walls themselves were crumbling. People they say are never enslaved, unless they have become slaves already. They swim into the Great leviathan’s mouth. He does not have to chase them. America seems to have fallen off its cultural path and is at war with itself on several fronts.

The term Death Wish entered the lexicon in the late 1970s after a series of crime dramas that stared Charles Bronson as Paul Kersey, a man who becomes a vigilante after his wife was murdered and his daughter molested by muggers. In a larger context, the concept of a death wish is a variation of Freud’s death instinct that can easily be applied to cultures, nations and even civilizations.

It was the former Trotskyite writer, James Burnham, who first popularized this Freudian concept with his 1964 seminal study, The Suicide of the West. Burnham exuded the same pessimism about the eventual decline of democracies that Alexis de Tocqueville had in his 19th century work Democracy in America. Liberalism to Burnham was the virus of the West that stripped the West of the core values it needed in order to combat world communism on a cultural level. He believed it was liberalism’s focus on the politics of guilt, fueled by its ideological nostra of egalitarianism and social justice that would inevitably lead to the implosion of Western culture.

Burnham’s ideas were a throwback to Oswald Spengler, an early 20th century German historian, best known for his book The Decline of the West, in which he presented his cyclical theory of the decline of civilizations. Decline had an important influence on historian Arnold J. Toynbee‘s similar work A Study of History. It was Toynbee who emphasized the natural rise and decline of civilizations in recorded history.

Like Toynbee, Bruce Thornton’s book, Decline and Fall, details the slow-motion self-destruction of the West from internal factors, caused by the loss of religious and moral faith. For this precipitous decline, he faults the philosophy Europe has adopted that includes Nietzsche’s nihilism, and Auguste Comte’s religion of man, or what we call secular humanism today. European decline has also been accelerated by a massive Muslim immigration. Through a natural policy of babies and ballots, Muslims are reproducing at such an alarming rate that they will be able to transform Western culture as a viable culture through their vote.

The master of all prophets of decline was Edward Gibbon. In his 1776 classic, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, he placed the blame on a loss of civic virtue among the Roman citizens. Romans had become lazy and soft, outsourcing their duties to defend their Empire to barbarian mercenaries, who then became so numerous and ingrained that they were able to take over the empire. He also blamed Christianity for making the Roman population less interested in the here-and-now and more willing to wait for the rewards of heaven. Many writers, including Murphy Cullen’s Are We Rome, are making these same kinds of comparisons. This underscores the historical truism that all cultures and empires are designed to fall upon their own swords.

In two of his best books, The Death of the West and The Day of Reckoning, Patrick Buchanan picked up where Gibbon and Burnham left off. He focused on the inherent contradictions that man’s freedom, unfettered by Christianity, has produced a culture at war with itself. Buchanan delineates a frightening laundry list of social and moral evils that have pervaded the culture in the last half-century.

Abortion, formerly a shameful crime, is now a constitutional right. Divorce, once relatively rare, is now commonplace. Pornography is the new addiction of choice for the middle class. Assisted suicide is here waiting for an opening at the banquet table, while Euthanasia has a seat at the head table. Extramarital sex is on the everyday menu, while homosexuality is one of the featured entrees. Like the figures described in Jonah Goldberg’s 2008 book, Liberal Fascism, liberals are acting like the proverbial barbarians within the gates, doing their best to undermine the very nature of the American republic.

Jesuit Father John Navone saw the decline of Western Civilization in the loss of tradition, especially among Catholics since Vatican II. Traditions are the cultural ties that bind humans to their culture. He decries the religious amnesia that plagues graduates of religious schools who do not know the most basic Bible stories, the history of Judaism or Christianity. Without the traditions of faith, language and history, individuals become religious and moral free agents, continually searching for anything that gives meaning to their lives. To Father Navone, the West has declined to what Vance Packard called fun culture, a hedonist realm of unfettered irresponsibility.

Many authors have disagreed with the alleged determinism of American decline. Collectively, they believe that Cultural Marxism has Western Civilization back on its heels and this is not the time to run around shouting that the sky is falling! There are many positives in Western Civilization that must be resurrected and shouted from the highest mountaintops. Fortunately, Western Civilization has not lacked for its apt defenders. One of the best ever was Christopher Dawson whose classic, Religion and the Rise of Western Culture, showed how important the monasteries were to the rise of learning in Europe.

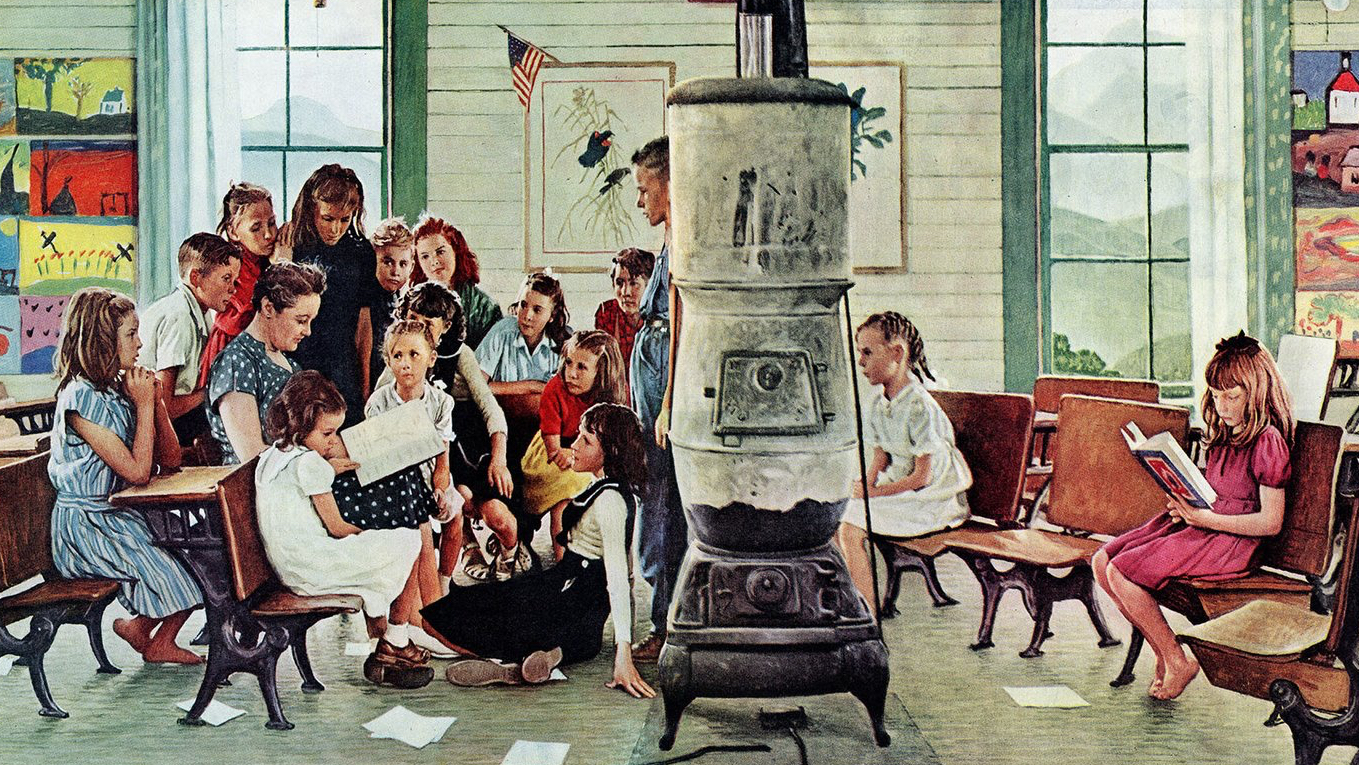

Following in his footsteps, historians such as Thomas Woods have taken up the banner for what one writer called contenders for their faith by demonstrating the Catholic Church’s vital role in Western Civilization. The author of How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization, Woods criticized the overall lack of knowledge of Church history among students and ceaseless tales of varying credibility about the Dark Ages taught in high school history classrooms. According to Woods, the Catholic Church gave birth to the distinctly Western idea of international law as well as the idea of natural rights. Woods wonders where Western morality would be without the Catholic Church. Contrary to Edward Gibbon, it is apparent that in many ways the Church filled the vacuum created by the collapse of the Roman Empire.

Robert Royal is another noteworthy apologist for Western Civilization and the Catholic Church. His 2007 book, The God That Did Not Fail, tells of Christianity’s role in world history, one in which the religion symbolized by the Cross acts as a lantern lighting the way for civilization. Like so many of the founding fathers, Royal argues that religion is necessary for a successful democratic culture. Sociologist Rodney Stark’s book, The Victory of Reason: How Christianity Lead to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success, joins the chorus in singing the praises of Christianity’s contributions to philosophy, the rise of capitalism and science and as well as democracy.

The best defender of the culture seems to be Dinesh D’Souza. His outstanding book, What’s So Great About Christianity, began as a reaction to the new militancy found among modern atheistic militia, such as Richard Darwin, Samuel Harris and the voluminous writing of the late Christopher Hitchens. He warns that Catholics must summon the courage to make the good fight to defend and advance the values of the civilization that emanated from their faith before it winds up on the refuge pile of history.

What’s so Good emphasizes three specific areas where the Church has been instrumental in elevating the former pagan culture of the West. The first area is Christianity’s role in providing the spiritual basis for limited government. In Matthew 22:21, Jesus taught his followers to render to Caesar what belongs to Caesar and to God what belongs to God. This can be construed to be the true origin of the separation of church and state. Not only does this separation help prevent the excesses of a theocracy, but it also gives credence to the idea of limited government, by advancing the concept that state power has a limit and must respect the conscience of each person.

D’Souza’s second thesis is that Christianity affirms the ordinary life. Christianity is not about elites and special powers but about all God’s children. Unlike other civilizations that have rested on elites, Christianity has gradually raised the status of all human beings because each one has been made in the image and likeness of the Creator. Christians were the first group to attack slavery as contrary to God’s law. Through its defense of human dignity, Christianity has provided the inspiration for campaigns to end slavery, establish democracy and promote self-government.

Evil has been another aspect that Christianity has addressed. While Plato felt that the problem of evil was a problem of knowledge, a common fallacy adopted by the secular left in current American pedagogy, the Greeks virtually ignored the problem of human evil. St. Paul knew only too well the evil lurking in his own soul, when he said, For the good that I would, I do not, but the evil which I would not, that I do. Christianity has been able to identify the universal contradiction inherent in all human beings.

Since the time of Christ, the family has been paramount to the Church and the quintessential building block of any sociology of civilization. In Greek culture, infanticide and homosexuality were prevalent. These sinful behaviors seriously undermined family life. It was Christianity that underscored the absolute importance of heterosexual monogamous love. It was Christianity that elevated the importance of woman as man’s equal, emphasizing her exalted importance to marriage, the family and child rearing. This is a far cry from the modern wisdom that regards men and women as fungible parts.

D’Souza shows how modern science owes much of what it is today to its Christian origins. Science is all about interaction and causation. Primitive man saw the world as wholly dependent upon the volatility of their many gods. Even though the idea of an ordered universe originated with the pre-Socratics, such as Thales, Heraclitus and Pythagoras, Christianity provided a rational sense of causation that is the metaphysical underpinning for the entire material universe. Science and reason became a seamless garment, woven together for the good of God’s creation. During the Middle Ages, many Catholic priests were scientists and the Catholic university became the center of learning about God and His universe. D’Souza underscores the fact that the greatest breakthroughs in science were largely the work of Christians. It was in Christian universities and monasteries that scientific knowledge was preserved and developed. Despite D’Souza’s arguments, the battle lines have been inevitably drawn.

Despite this, the signs of irreputable damage to the culture are shining more brightly now. For centuries, the religion of Jerusalem metaphorically blended with the science of Athens. It was not until the secular atheism of the Renaissance and its stepchild, the French Revolution that the two cities were cast against each other in a cultural war that still divides Western countries. It has been the atheism of many scientists that has rent the unified fabric of science and religion by unwittingly plunging into the metaphysical sea of causation and origination. No valid scientific method can shed any light on man’s origins, an inquiry that is best left to the theologians.

It was within the context of Western Civilization that the United States Constitution developed out of the Christian debate on tolerance and freedom of conscience. The debate also advanced the idea that government should refrain from making laws that would impede the religious freedom of individuals and churches. This has been the guiding principle in America until the secularists in the 1950s reversed Thomas Jefferson’s concept of the wall of separation of church and state in order to eliminate religion from the public sector.

Dineen points his finger at the philosophy behind the Constitution as largely responsible for the failure of both classical and progressive liberalism to stem the inherent signs of their self-destruction and with that the country’s sense of order. According to George Weigel’s book, The Cube and the Cathedral, secularism is now one of the banners behind which modern European man wishes to march. This serves as a warning that all Americans should heed.

Materialism is another threat to Western Civilization that should not go unrecognized. Catholicism has always warned about the dangers of greed and envy often found in capitalism, globalism and free trade. It has also emphasized the importance of private property for freedom, the family and religious belief, not financial empire. With political and cultural entitlements, greed now seems to cut across all classes in America.

While there is little doubt that given its university of intellectual and rational truth, Americans educated in the traditions of Western Civilization should be able to fathom any argument. But given the 21st century’s oversized uberrclass of materialist and hedonistic students, who have been taught by their progressive teachers, how to feel and not how to think, the playing field has transferred to the universal world of social media for each person to ascertain his or her own truth, thus reducing homo sapiens to a behavior more appropriate for a jungle than a civilization. Can Western Civilization adjust to this salient change? Or will it succumb to the weakened wall and fall of its historical sword?