Charles Dickens and St. John Bosco, the first, a London/Victorian novelist (1812-1870), the second, a Turin priest/saint/memoirist (1811-1888)—I am struck by similarities on a page from each. The chief of those similarities is one we do well ever and always to consider. It is this: the idea that no child is so neglected as the one who is not introduced to prayer. Yes, the pages have other similarities—their focus on street kids, their dialogues between an adult-witness interrogator and a street toughie, their several brilliant, tragicomic brushstrokes, etc.—but ultimately what they most have in common is the idea I’ve just articulated.

Consider, first, the Dickens page: It’s that potent one in his Bleak House (1852-53) in which the writer lets have it all of institutional Christianity, as well as, too, all of secular society, for its neglect of the Industrial Age’s street children. That would be, of course, the “death of Jo scene” at the end of the novel’s 47th chapter. Do you recall it? Wow! What a scene! I will not review here all of its leadup–wherein Woodcourt, who is a doctor and who is the scene’s interrogating, adult witness, gets from Jo, the teen corner sweep, this heartbreaking profile of his ragged, pestiferous, under-the-radar, London existence:

That he is Jo, family name unknown; that he is, as I say, a crossing sweeper, a broom his livelihood; that he “know[s] nothink,” nor reads; that the police have called him the Tough Subject; that on some few days he gets a coin, but on more he gets “Move on,” and “Move on,” and “Move on” once more. And, lastly, “Wishermaydie!” Woodcourt hears Joe say that several times. It’s the boy’s ominous version of the already ominous Cross my heart and hope to die that you and I are familiar with.

No, rather than review those preliminaries, I’ll pick the page up at that moment in the pair’s interaction when this out-of-the-blue question is suddenly spoken by Woodcourt, who, you should also know, can see that Jo is dying.

“Jo! Did you ever know a prayer?”

“Never knowd nothink, sir,” says Jo.

“Not so much as one short prayer?”

“No, sir. Nothink at all,” says the boy again, adding this time a note about his having overheard others praying, albeit, mostly as if they “was talking to themselves, or a passing blame on the t’others.”

And so on, the pair’s digressive dialogue, until next Woodcourt goes back to the topic that is clearly foremost on his mind: “Jo, can you say what I say?”

Yes, Jo can do that.

“OUR fATHER,” prompts Woodcourt.

“Our Father!—yes, that’s very good, sir,” the boy replies, as if trying out something new.

“WHICH ART IN HEAVEN.”

“Art in Heaven—”

And so on, on the page, for only the least bit longer, for, sad to say, Jo passes away in the prayer’s hallowing verse. And then the narrator, who is now more Dickens than anyone else, lets have it, in full-throated perorative style, those he would wish to rebuke:

‘Dead! your Majesty. Dead, my lords and gentlemen. Dead, Right Reverends and Wrong Reverends of every order. Dead, men and women, born with Heavenly compassion in our hearts. And dying thus around us every day.”

Strong stuff, you say, as have, I assure you, countless of the novel’s scholarly readers. And what is its takeaway? Why, of course, the idea that I’ve articulated above! Think about it. If Woodcourt had not been there, then Jo, already a neglected, abandoned child in every material, societal, and familial sense, would not even have had a prayer to die with. That’s the nadir of child-rearing neglect in Dickens’s view.

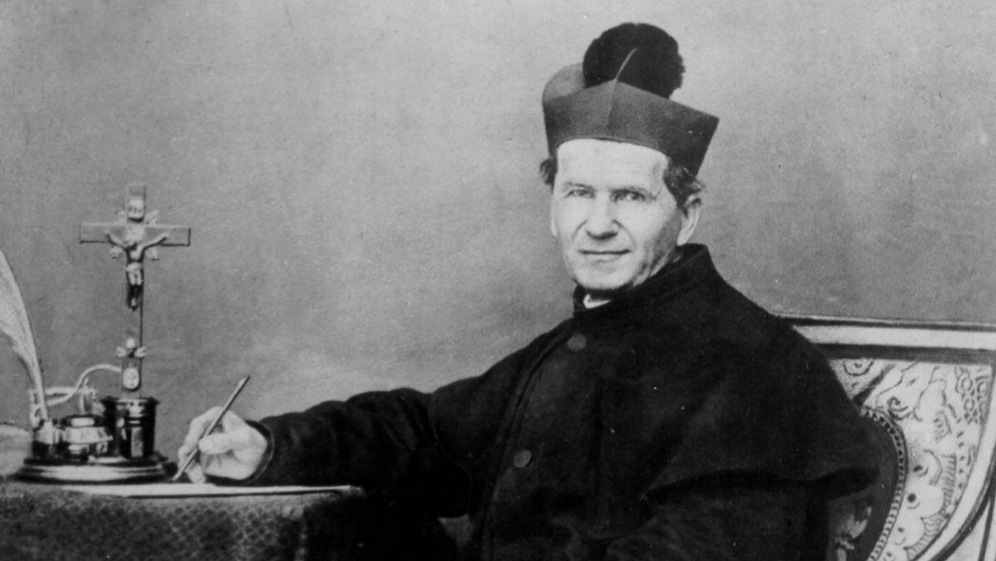

Strong too is the page from Don Bosco. I give it to you as I get it from, yes, the saint himself in his autobiography, Memoirs of the Oratory of St. Francis de Sales (1876), but also, too, from his contemporary and biographer, Father John Lemoyne, whose nine-volume, Boswellian The Biographical Memoirs of St. John Bosco(1898-1917) frequently supplies details that Bosco in haste or humility leaves out. Again, consider:

At the page’s start, Don Bosco—now a rookie priest in search of his life’s mission—is vesting for Mass in the sacristy of the church attached to the Institute where he has been studying. It’s the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, December 8, 1841—a cold day, so cold in fact that a street boy has come into the sacristy seeking warmth. Or maybe the boy is there because he has followed Don Bosco in. Indeed, at the top of the page on which we’re reading, Don Bosco has just told us that on his frequent way to this church it has been his custom to greet the swarms of street kids in those Industrial Era days shifting for themselves and/or making mischief in and throughout Turin, and that sometimes some of them have followed him in. For that reason, it does not seem strange to him that the boy should be in the sacristy. Yes, the kid’s threadbare coat and laborer’s physique are menacing, but Don Bosco knows his type, and is not put off by it.

And there are other reasons, too, why the priest knows his type. Not too long ago, he himself was the next-best thing to the entirely unlooked-after teen that this boy transparently is. That was in the adolescent era of his life, when his widowed mother, Mama Margaret, decided that, all hard, hard choices considered, it was necessary that the youngest of her three sons go to a neighboring farm to live and work. So, yes, though he does not say so in his Memoirs, Don Bosco, who was that third son, knew what it meant to be one’s family’s ill-fitting piece.

Or maybe the kid has a job. If that’s the case, Don Bosco knows him for that reason too. For, yes, when he was a teen, he for a time earned his keep by stitching and hemming in a tailor’s shop.

And, lastly, the young priest is not a-feared of this boy because he has seen worse, far worse, in the prisons where he sometimes ministers. There, says Don Bosco on the page that immediately precedes this one, he has seen all “the misery and malice,” ‘lice,” hunger, “public disgrace” and “personal shame” that were a teen’s standard sentence in a mid-19th-century, Turin lockup. Those, of course, were but sugar-glazed euphemisms for the horrors that he had actually seen. And, yet still, we get their point. And, as a result, we know that this shivering lad who is now watching Don Bosco vest as if he is putting on sweaters is not understood by the priest to be of that hellish venue’s hardened caste. If anything, going forward, Don Bosco would like to do all in his power to keep the boy out of that place.

But now, suddenly, there is a commotion. It’s the sacristan. He is berating the boy for not knowing how to serve Mass. Absorbed in his pre-Mass devotions, Don Bosco has missed the first part of the church-custodian’s and the boy’s scuffle. But now, when he opens his eyes, a scuffle is, indeed, the state of affairs, for, in addition to scolding the boy, the sacristan is poking and flailing at him with his long-handled duster, and urging him in the direction of the sacristy’s door. Don Bosco thinks to intervene—before the sacristan gets his eye blackened, that is—but just as he moves to do so, the boy ducks under one of the sacristan’s maladroit flourishes and is out the door.

A reckoning ensues between the priest and the sacristan. The latter feels that some great principle of the cosmos is violated whenever a boy who doesn’t know how to serve Mass comes into a sacristy. Don Bosco feels otherwise. He also feels that boys ought not be hit. And lastly he tells the sacristan that the kid was his friend. “Call him back at once,” he says. “I need to speak with him.”

Soon thereafter, therefore—after Mass, which the boy attends—Don Bosco and the teen have a conversation like the one that went down between Woodcourt and Jo, only this time the interviewee is more demoralized than he is dying, and the interrogator is in no mind to bury anyone. At the interview’s start, Don Bosco learns the following:

That the boy’s name is Bartholomew Garelli. He is sixteen, from Asti, a bricklayer, and an orphan. Yes, both of his parents have passed away. As for reading and writing, “No,” Bartholomew says in answer to that prompt (just as might Jo), “I don’t know anything.”

And so on, on the page, with, for sure, many a detail left out, such as, for example, Don Bosco’s responses to the litany of sad facts that were the boy’s woeful curriculum vitae. However, the Boswellian of our page’s sources suggests that the cleric was indeed attending to what he was hearing and responding appropriately. It does so when next Don Bosco asks the boy if he can sing. That, you see, is the priest offering the boy a chance to say something good about himself. Yes, think about it. From having parents, to meaningful winter dress, to learning, to serving Mass, poor Garelli has not had a single bright spot on his resumé, and who is to blame for that?

Unfortunately, the kid can’t sing either.

So next Don Bosco asks, “How about whistle?”

Yes, Garelli can do that, and, for sure, though the page does not say so, he whistles for the priest—very likely one of those gang-member whistles by way of which pickpockets signal to one another the approach of cops.

Don Bosco is impressed.

And so on, on the page, until lastly the rookie priest, having promised the boy—who clearly has been hit a lot in his lifetime—that he would not be hit if he came back for catechetical instruction the following week, gets in return from Garelli an assurance that he would return. Indeed, at Don Bosco’s prompting, the two decide that they won’t even wait the week but instead begin the lessons right then and there. And, thus, Don Bosco moves to begin the instruction with a prayer. Only the boy doesn’t join him in the sign of the cross. And what’s that all about? Is the teen so ignorant of his faith that he doesn’t know the beginning and ending of almost all of its formal prayers? And, another thought, was he lying a few moments earlier when he told Don Bosco that he had already had some catechetical instruction, that, indeed, he had already made his first confession?

In truth, neither of our page’s sources tell us that these questions passed through Don Bosco’s mind at this moment. However, they have no need to. For the last of the questions, the possibility of the boy’s having lied to him is not what would have most mattered to Don Bosco. No, what bothered him was the fact that the boy no more had a prayer in his head than a lining in his coat. We know this because of what both sources say he did next—namely, teach the boy to make the sign of the cross.

And that’s the chief difference between Don Bosco’s page and Dickens’s. At the end of the latter, a prayer is going unfinished. At the end of the former, a life of prayer is just beginning. That’s a significant difference. But not as significant as all they have in common.