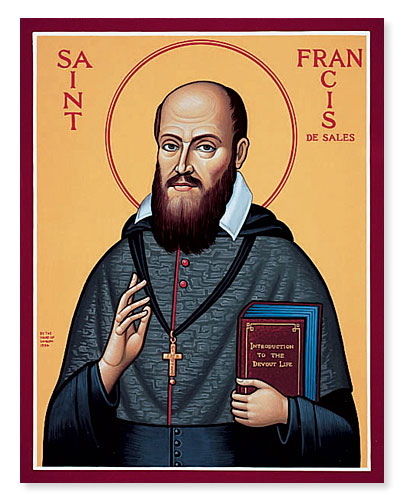

Almost 400 years ago a woman who had lived a very sinful life went to the great bishop St. Francis de Sales and made a good confession. After receiving absolution, she asked him in a spirit of shame and embarrassment, “Father, what do you think of me now that you’ve heard all the terrible things I’ve done?” He reassured her by answering very gently, “Child, I look upon you as a saint. Your past life no longer has any existence, for you have been raised from a life of sin to a life of grace.”

This is how every priest feels after hearing a sincere confession; in fact, being able to give absolution to a humble and honest sinner who’s turned back to God is one of the greatest joys any priest can know. Even a routine confession, in which a person confesses the exact same sins as before, allows a priest to be an instrument of God’s mercy — and that’s a humbling and privileged experience.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t happen often enough; the Sacrament of Reconciliation isn’t used as much as it should be. There are many fewer confessions today than in the past — yet at the same time, at every Catholic Mass, almost everyone comes to Holy Communion. We can’t look into anyone’s heart or conscience, but it’s hard to believe that no one is ever guilty of mortal sin — and receiving Communion in the state of mortal sin is itself a further serious sin and a sacrilege (“Catechism of the Catholic Church,” numbers 1385, 2181). Even if most of us never commit any truly serious offenses, we can all benefit from regularly confessing our sins — and while priests today seem to be busier than ever before, most of us would be happy to spend much more time in the confessional if we knew we were thereby helping all our parishioners grow in holiness.

Jesus spoke of the grain of wheat falling to the earth and dying, thereby producing a rich harvest (John 12:24). One important way of dying to ourselves is by humbly admitting our sins and sincerely seeking God’s mercy; this allows His grace to work within us in a wonderful manner. This is especially true of the sacrament of reconciliation, for it is the deepest and most powerful experience of God’s mercy that any of us can ever receive.

Many times people ask, “Can’t I just confess my sins to God in my heart?” Yes, we can and should do this every time we realize we’ve sinned — but sometimes we also need to receive the actual sacrament. Scripture tells us (Matthew 18:18; John 20:21-23) that Jesus gave His Church the authority to forgive sins — but this requires sinners to verbally express their need for forgiveness. Also, because of our human nature, we sometimes have the need to hear, through the words of the priest, that God has forgiven us. Furthermore, all our sins hurt the Body of Christ, even if no one ever knows about them, because they make us less loving and less capable of sharing the Good News through our words and example. Since our sins have a negative effect the Church in these ways, it simply makes sense that some of our experiences of God’s mercy occur directly through the ministry of the Church.

What does our Catholic teaching on reconciliation mean in practical terms? First, of course, we should come to confession as soon as we’re aware of having committed a serious sin, and delay receiving Holy Communion until we’ve done so.

Second, even if we haven’t committed any mortal sins, we can still benefit from receiving the sacrament every few months, and at least once or twice a year. We might prepare ourselves by using a good examination of conscience and, even more importantly, by asking the Holy Spirit to help us bring to mind anything that needs to be confessed.

Third, it doesn’t matter whether we kneel behind the screen or sit and talk to the priest face-to-face; in either case, the seal of the confessional means that he may never, in any manner, for any reason, reveal anything we confess; he’s not even allowed to bring up and discuss one of our sins with us at a later date. Also, I and other priests don’t look down upon people because of what they’ve confessed; many times we find ourselves admiring their honesty and humility — so penitents can afford to be completely honest and open in the confessional.

Lastly, it isn’t necessary to know the precise formula for confessing one’s sins or the exact words of the Act of Contrition; if need be, Father will help us through the confession, step-by-step. If we’re nervous or frightened or confused or embarrassed, we should tell the priest before beginning, allowing him to help make the experience easier for us.

Most of us understand why it would be foolish for someone to stubbornly refuse to go to a doctor or dentist for a prolonged length of time; denial of this sort could be extremely dangerous to the person’s health. The same idea applies even more powerfully to our spiritual well-being. We need the sacrament of reconciliation — not only to be restored to God’s grace if we’ve committed a serious sin, but also to help us struggle against and overcome our lesser sins, our bad habits, and anything else that may be preventing us from growing closer to God.

Knowing the weakness of our human nature, Jesus gave His Church the sacrament of reconciliation as a remedy and gift for sinners — and all of us qualify. Whatever you do, don’t waste this wonderful and amazing opportunity to be cleansed once again and made holy in God’s sight. Jesus wants to draw everyone to Himself (John 12:32) — and one of the ways He is inviting you is through this Sacrament.