In 1938 Elizabeth Fanning was born in Dearborn, Michigan. Betsy, as she was known, suffered from childhood leukemia, which at that time was a death sentence. She was listless, wouldn’t eat, and was losing her hair; doctors would have recommended her spleen be removed, except they knew she was too weak to survive the operation. Her desperate parents didn’t know what to do, but then a relative suggested taking Betsy to see a seventy-year-old Capuchin priest at St. Bonaventure Monastery in Detroit, saying, “He’s a saint, and he heals people all the time.” Accordingly, Betsy—who at a year-and-a-half still couldn’t walk—was carried by her parents to St. Bonaventure’s, where Fr. Solanus Casey graciously spent time with them, even though there were many people waiting to see him. He spoke with Betsy for a few minutes, and ended by saying, “You’re going to be all right, Elizabeth.” The parents left with new hope, and on the drive home to Dearborn, they noticed with amazement their daughter for the first time seemed lively and alert and interested in everything. They stopped at a restaurant to celebrate, and as Mrs. Fanning later said, “The place was crowded—and Betsy—who only an hour before had been lying in my arms as limp as a rag doll—immediately became the life of the party. She waved to the people around us, jumping up and down. She was full of life.”

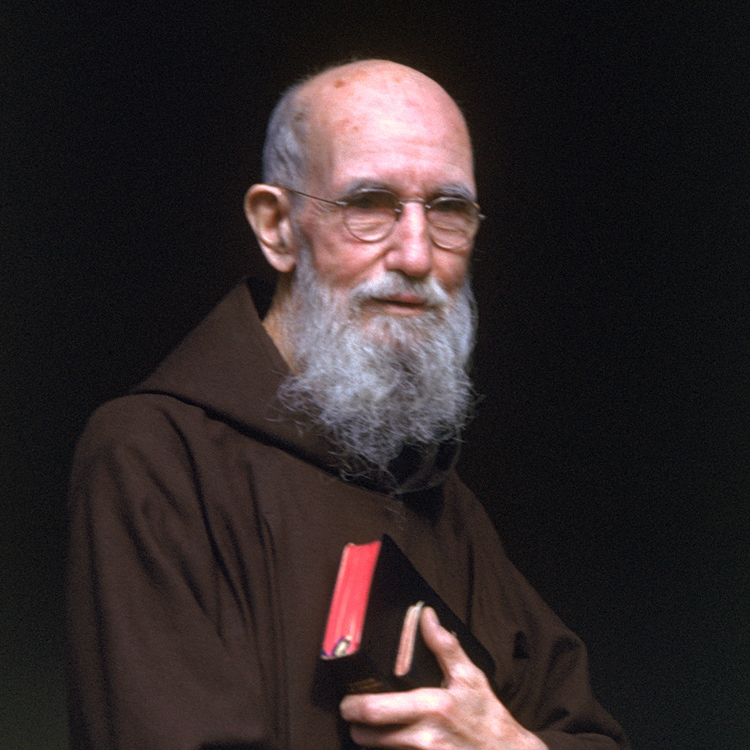

This was one of many healings and miracles attributed to the simple but holy Capuchin priest Fr. Solanus Casey. He died in 1957, but is still widely remembered and revered in southeast Michigan. One of sixteen children, Bernard Casey was born in Wisconsin. He entered the diocesan seminary at the age of 26, but struggled because the courses were taught in German and Latin. When the seminary dismissed him, he was told, “Try a religious order; perhaps they’ll ordain you a simplex priest”—meaning one able to say Mass, but not allowed to preach or hear confessions because of intellectual limitations. After making a novena for guidance, Casey heard a voice telling him to “Go to Detroit,” which he did. The Capuchins accepted him, and eventually he was ordained in 1904, but as a simplex priest—a humiliation he accepted by surrendering himself completely to God’s will. His many years of service in New York and especially in Detroit—in which he had the humble position of porter, or door-keeper—led to many miraculous healings through his prayers, and people constantly came to see him or wrote letters requesting his intercession. Through it all, Fr. Solanus remained humble; for instance, no one who once heard him play the violin ever asked him to do so a second time, for it sounded like he was torturing the instrument. That was all right with Fr. Solanus, for he was the first to admit he was a terrible musician. During his final illness, one of his nurses, a young nun, flippantly remarked, “How about a blessing, Father?,” and he answered, “Sure, I’ll take one.” After his death a letter from Rome was found among his papers, removing his simplex status and granting him official permission to preach and hear confessions—but in his humility, Fr. Solanus—who was given the official title “Venerable” in 1995—never made use of this privilege (Patricia Treece, Nothing Short of A Miracle, pp. 33ff). Humility allowed Fr. Solanus to do great things for God, and the same can be true for us—for God’s grace works only through those who strive to be humble in His sight.

Jesus is the perfect example of humility. The Book of Leviticus (13:1-2, 44-46) tells us how those afflicted with leprosy were required to keep their distance from everyone else. When a leper violated this law by approaching the Lord (Mk 1:40-45), He didn’t rebuke him, but graciously responded to the man’s request for healing—even though it ended up costing Jesus His privacy. Being humble includes a willingness to help others whenever we can; as St. Paul says in his Letter to the Corinthians (1 Cor 10:31-11:1), “I try to please everyone in every way, not seeking my own benefit but that of the many. . . .” Paul in turn advises us to “do everything for the glory of God,” for only in this way we can experience that happiness which comes from being perfectly in accord with God’s plan—a happiness and peace this world cannot give.

During the American Revolution, General George Washington was conferring with the French patriot General Lafayette; a slave passed by, tipped his hat, and said, “Good morning, General Washington.” To the shock of Lafayette, the American leader removed his hat, bowed his head, and wished the black man a pleasant day. “Why did you bow to a slave?” Lafayette asked, and Washington replied, “I would not allow him to be a better gentleman than I” (Knight’s Master Book of 4000 Illustrations, p. 312). Almost everyone agrees George Washington was a great man who achieved historic deeds—but this would not have been true without genuine humility on his part. Pride interferes with the workings of divine grace; only those who try to be humble can be true disciples of Jesus—a truth attested to by many of the saints. The famous hermit St. Anthony of Egypt wrote, “I saw all the devil’s traps set upon the earth, and I groaned and said, ‘How can anyone pass through them?’ And I heard a voice saying, ‘Through humility.’” The great bishop and scholar St. Augustine stated, “If you should ask me what are the ways of God, I would tell you that the first is humility, the second is humility, and the third is still humility. Not that there are no other precepts to give, but if humility does not precede all that we do, our efforts are fruitless.” According to St. Benedict, “We descend [toward hell] by self-exaltation, and ascend [toward Heaven] by humility.” In the words of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, “The gate of Heaven is very low; only the humble can enter it.” Lastly, Venerable Solanus Casey himself said, “If you can honestly humble yourself, your victory is won.”

Jesus wants each of us to be victorious—not by denying our own goodness, but by giving God the credit for every good thing we do; not by acting as if we’re less valuable than others, but by seeking their well-being in addition to our own needs and interests; and not by denying our talents and abilities, but by using them for God’s glory, instead of our own. Pride is poisonous, and leads to spiritual death; humility is spiritually fertile and life-giving, and leads to everlasting happiness and glory. As the life of Venerable Solanus Casey shows, the more we humble ourselves, the more we give the Lord permission to work in our lives in a powerful and wonderful way. With the help of God’s grace, let us make this manner of life our goal for today, tomorrow, and all the days to come.