German philosopher Frederick Nietzsche made quite a stir in the late 19th century when he informed the world, God is dead! Most people have misunderstood what he meant. He wasn’t saying that God had lived then died. Nietzsche meant that He was irrelevant. In his sophisticated world of progressive thinking, no one of any education, intelligence or cultural breeding believed in God any more, so He was as good as dead.

A parallel situation evolved during the late 20th century. One of the essential teachings of the Catholic Church is that each individual has been blessed with an immortal soul that was created in the image and likeness of God.

America’s cultural elite has focused its new militancy on completing the work of Satanic disciples, such as Nietzsche by dedicating themselves to the final destruction of all the superstitious remnants of Christian belief. Their latest target has been the destruction of belief in the human soul. To accomplish their final victory, atheistic scientists had to conjure a way to kill the soul. According to their approach all man’s emotions, feelings and morality were mere sense impressions, which is the spontaneous result of biochemical changes.

This new strategy first became apparent in 1996 when Forbes magazine published Thomas Wolfe’s essay, Sorry but your soul just died. His article defined the boundaries for the final battle by focusing on brain imaging, the new technology that watches the human brain as it functions in real time.

While brain imaging was invented for diagnostic reasons, Wolfe underscored its importance for broaching metaphysical and eschatological issues, such as the complex mysteries of personhood, the self, the soul and free will. He envisioned that neuroscience would have an enormous impact on how people viewed life, death and other human beings. He predicted that this new science was on the threshold of a unified theory that will have an impact as powerful as that of Darwinism 100 years ago.

The debate over man’s soul dates back to 17th century French philosopher Rene Descartes’ dictum Cogito ergo sum (I think therefore I am). Traditionalists have always regarded his maxim as indicative of man’s dual nature of body and soul.

This gave rise to the ghost in the machine fallacy, the notion that there is a spiritual self somewhere inside the brain that directs and interprets its operations. Wolfe’s article challenged this idea, stating that neuroscience proved there is not even one place in the human brain where consciousness or self-consciousness is located.

According to Wolfe, science and pharmacology have replaced religious faith and devotion by altering the chemistry of the brain, which also dulled the moral sense. Echoing Nietzsche, Wolfe predicted that the next generation would believe the soul, the last refuge of values, is dead because educated people no longer believe it exists. Wolfe believes that the soul for the next generation will occupy the same intellectual realm as witches and warlocks.

It is also clear that the death of the soul movement is symptomatic of a larger scheme. Cryogenics, the freezing of the dead so that medical science can later resurrect them, is a part of transhumanism, a utopian attempt to establish man’s earthly immortality.

To fill the void created by the alleged death of the soul, these modern Doctor Frankensteins have sacralized the earth and made man’s body the object of immortalization. So while they believe man does not have an eternal soul, his body through scientific discovery and manipulation can eventually achieve earthly immortality.

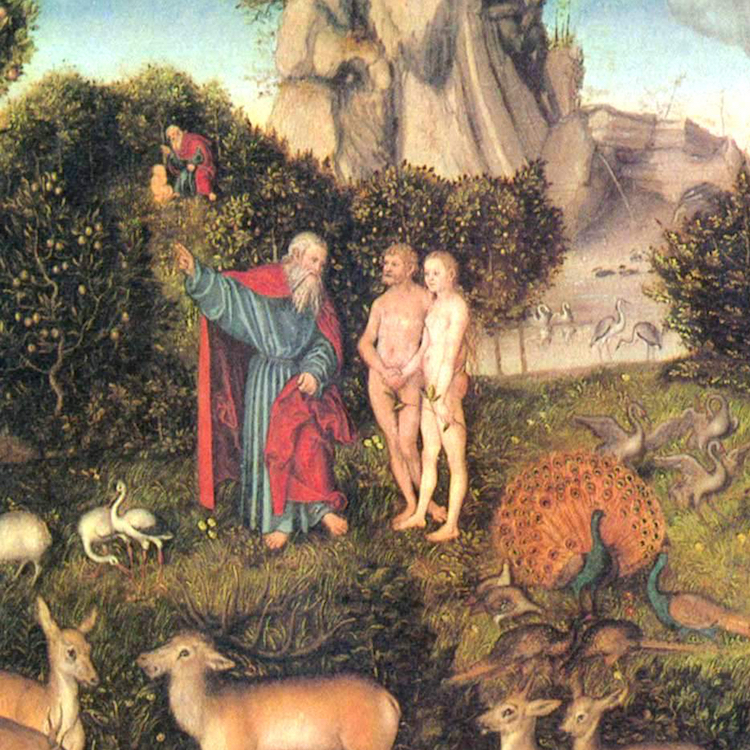

This effectively flips Christianity on its head. It is another and maybe more dangerous attempt to replace an eternal God with an eternal man, who is the fulfillment of the serpent’s promise of you shall be like gods, in the Garden of Eden.

How important is it for us to understand and oppose this new attack? If science can eliminate the immortal soul, then Christ’s death, Resurrection and our entire Catholic faith are all in vain.