The first line from soul singer Sam Cooke’s 1960 hit, Wonderful World, begins prophetically Don’t know much about history! How is it that Americans seem so ignorant of their own history? And why is it what they presume to know sounds as if it had emanated more from Winston Smith’s Ministry of Truth than an accurate rendition of history. When one adds Spanish Philosopher George Santayana’s oft quoted adage: Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it, perhaps we have a clue. There are those among us who try to cancel or rewrite our history so that it will be possible for Americans to have a true picture of our past that we can compare with our present.

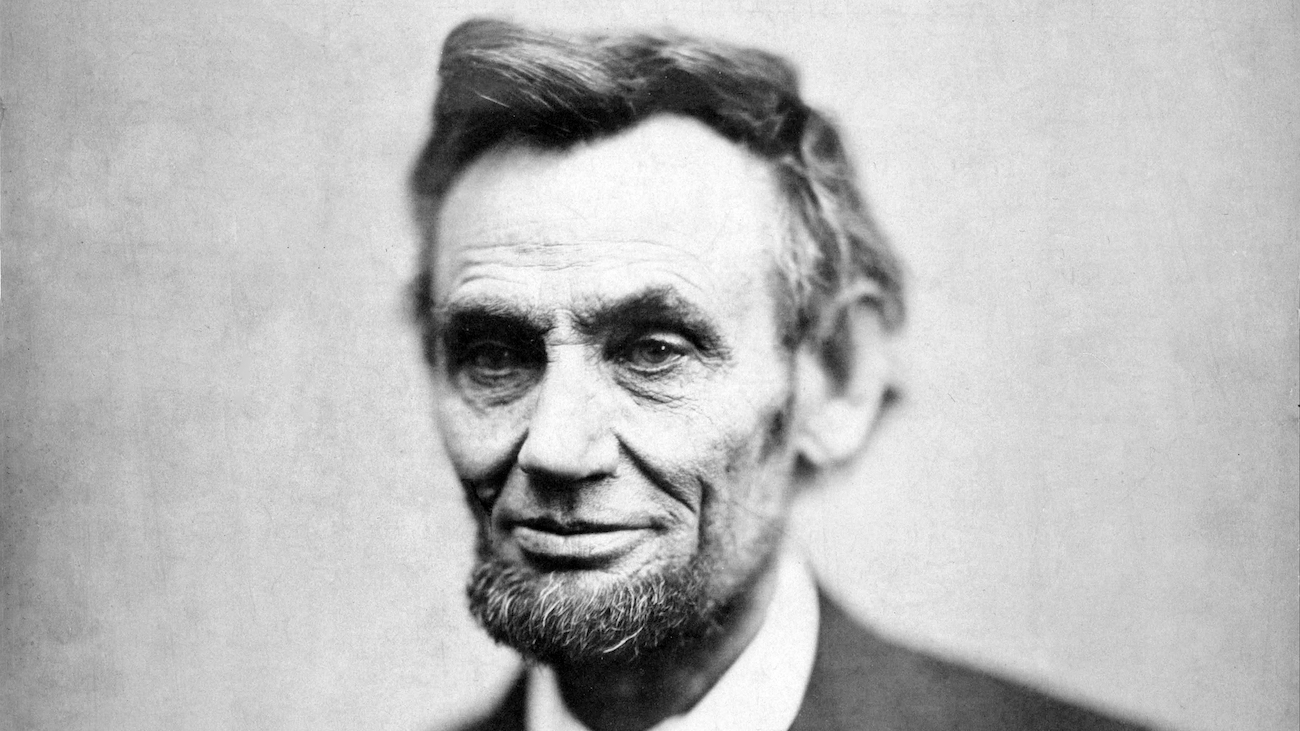

In what is most likely the most often quoted excerpt from George Orwell’s prescient novel, 1984, the masterminding Big Brother declares that He who controls the past controls the future. As someone who has three history degrees framed and hanging on a wall in my den, it is painful for me to read all the blather and artificial pontificating in the newspapers about our first cultural war. Historians tell us that the war was all about slavery. The facts about Lincoln’s motivations in 1861 tell another story. For at least the first half of the Civil War, Lincoln agonized over the break-up of the Union and not the eradication of slavery.

For too many their analyses seem very simplistic and almost chimeric in their exposition. They lack the nuances that is the gray shades that give substance and reality to the study of history. To make an objective study, one must have an almost theological understanding of mankind and his systemic flaws. This is something no one weaned on the mother’s milk of Progressivism is likely to understand.

Progressivism is an elitist ideology that emanated from the socialistic impulse of the 19th century and the utopian principles of the Philosophes, who gave us the French Revolution in the 18th century. Their leading spokesman was Jean Jacques Rousseau who believed all men were essentially good and that it was their institutions, such as throne, Church and shopkeeper that were responsible for all the evils in the world. Rousseau failed to note the basic contradiction in his thinking that men created and ran all the institutions that societies had ever established.

Consequently, with a flawed human nature as an essential component of not just American History— but all history, the most salient cause of the Civil War took place at the Constitutional Convention which began in Philadelphia in 1787. The leaders of the American colonies were faced with the herculean task of unionizing thirteen disparate colonies, which is akin to a popular trope of trying to organize a clowder of cats. They had tried to form a national government right during their surprising victory over the British empire but failed dismally. The Articles of Confederation was a loose union of 13 separate entities, more likened to a voluntary partnership. Without any viable power, the Articles were doomed to failure from their inception. Consequently, our once revered founding fathers were faced with writing a document that actually had some teeth in it.

Slavery quickly surfaced as a bone of contention between the delegates at the Convention. There is is religious adage that one should never compromise on a moral issue. Many in the North saw slavery through this Christian prism. The South did not. To them it was strictly an economic necessity. To heal this division or at least put a surficial bandage on it, the delegates agreed to a series of compromises on population and territorial rights that allowed the institution of slavery to exist.

One might blame the Northern leaders for their amorality in these compromises. Presentism is a popular historical fallacy that modern historians often employ. It means judging the past by the mores of the present without any concern for historical context. Though absolute morality is unchanging, the times, customs and social mores often perceive morality through a glass darkly. For historians, it is unfair to judge past generations by the mores of their times.

No union was possible without the moral compromises. Perhaps splitting into two separate nations might have been the better solution but the threats encircling the nascent nation seemed to preclude that. Most Northern leaders believed the issue would be moot in a generation or two. In 1789 their perception was that slavery was a dying institution. Housing and feeding the slaves was very costly. The work of harvesting cotton was not only laborious, but painful slow and inefficient. Before their crop could go to market the seed had to be manually separated from the cotton. This was not cost-effective.

Northern leaders were well versed in philosophy, law, economics and even theology. Though they read the Bible, they were not prophets. None could have predicted that a Connecticut Yankee at Yale University, Eli Whitney, would invent a gin that would separate the seed from the raw cotton, quickly and efficiently. It revolutionized the cotton industry, exponentially increasing the demand for more slaves.

Other forces were at work. Many people in the Northern colonies had already had a revulsion to slavery before the Revolution. Manumission of slaves societies popped up in several areas in the North, especially in New York City, which laid the foundation for the Abolition Movement of the coming century. A founding father, John Jay, who became the First Supreme Court Chief Justice, worked in the New York Manumission Society for years before assuming his federal office

After the ratification of the Constitution, it became evident that the 13 colonies had coalesced into two distinct sections, the North and the South. The North had started its industrial system while the South had chosen to concentrate on its largely agrarian economy where Cotton was King. The term Sectionalism came into vogue. But that neologism does not communicate just how unalike these sections had become. Like a bad marriage, they had grown miles apart. One need only read the book or see the film based on Margaret Mitchell’s classic, Gone with the Wind, to vicariously experience the other-worldly culture that had already matured in the South. Their plantation owners viewed themselves through the idyllic lens of Medieval History where white serfs were essentially the slaves of that time. They felt their society was no different. It is not surprising that the most popular book of the ante-bellum period of Southern history was Ivanhoe, published in 1819. It depicted Sir Walter Scott’s romantic version of the 12th century, replete with its pageantry, chivalrous codes and reliance on personal honor.

Two distinctive cultures had grown side-by-side within America’s tenuous Union. When they went to war, both sides, especially the South, were trying to preserve or extend a culture, that is a way of life. Thousands of Southern soldiers, most of whom did not own a slave, were fighting for their families, towns, cities and states, not any abstract principle.

While it can be argued that slavery served as the face of Southern culture, it was but one of its many cultural ingredients. The South did not invent slavery. It was virtually universal all over the globe and had existed for several centuries. The South procured their slaves from tribal leaders in Western Africa, who sold off their human plunder acquired from the rival tribes they had defeated in battle. The truth of history is that peoples of different races and cultures cooperated in the slave trade. The South argued that their peculiar institution, as they euphemistically called it, was no worse and maybe even better than the wage slavery that the Northern industrialists were practicing on their cheap labor in the factories all over the North.

While the plantation owners were responsible for the food and lodging of their workers, the industrialists cared little for their workers basic needs. While the South had a point, the missing word is the workers in the North were free to learn, improve their skills and qualify for better jobs. By stark contrast, the Southern slaves and their families were chained to the plantation for life.

Yes, the Southern plantation owners profited from their cheap labor because the slaves were useful to their economy. Temper that with the fact that the blacks, who had to be imported from thousands of miles away, were not the first choice for the South’s cheap labor. The planters had tried white indentured servants as workers in the field in the blazing Arkansas or Georgia sun. They could not survive the oppressive heat. The same was true of Mexicans and the American Indians. But other countries South of the American border, like Cuba, had used African blacks who could adapt to the stifling heat more readily. In fact, it was environmental and geographical determinism that were most responsible for the introduction of slavery in 1619. To call it Racist a word that did not exist to well after the Civil War was over, does not conform to the facts of history.

In the 21st century, the objective story of Southern slavery has succumbed to the ideological dictates of the Marxist Left and its minions in the press. Too many people get their knowledge of History from the New York Times, which disgraced itself with its publication last year of The 1619 Project, an erroneous series of essays that portrayed America as systemically racist for its entire history. With such a blatant abuse of America’s past, the Times had solidified its role as lead gun in the Marxist Ministry of Truth.

By the late 1850s, after many a bitter legislative defeats over economic and territorial issues, the South painfully realized that because of the oppression it suffered under the North’s political and economic superiority, the South’s future as part of a United States, was on its last legs. As a result, their Secession Movement began in earnest, especially South Carolina which became the seedbed of rebellion. Its leaders did not do this without some justification. From the very beginning, in 1789, Southern leaders believed that their agreement to the slavery compromises, constituted a voluntary partnership, with the implicit right to leave if circumstances warranted their exit. It is my understanding that most Southern states would probably not have joined without such an escape clause.

The leaders in the North did not agree with their legal reasoning. Lincoln fought very hard to explain to their leaders that somehow the Union was inviolate like a mystical marriage that no man or state could invalidate. An intact union was the president’s main reason for sending an Army of federal troops into Virginia. By 1863, Lincoln had been hardened by thousands of casualties, a critical press and an angry electorate, prompting him to try a new approach. He used the abolition of slavery as his main inspiration to rally the country. Unfortunately, he did not live long enough to experience the joys of his heroic efforts, having succumbed to an assassin’s bullet shortly after the Appomattox peace.

That was after over 675,000 soldiers had perished in battle or from disease and Southern plantations, homes, businesses and farms had been burnt to the ground. A vindictive Republican Party, sorely lacking the magnanimity of a Lincoln or a Grant, sought to punish the South for its transgressions by occupying all the rebel states and treating their citizens as virtual prisoners of war. Their brutal behavior, mostly out of revenge, when coupled with the elevation of their former slaves to high positions in government and business without a shred of preparation, enraged the Southerners. With the White House at stake in the highly controversial election of 1876, the Republicans sent the slaves they had freed, not to the back of the bus but threw them under it. They pulled all the troops out of the occupied territories in the South and the erstwhile slaves were left to the mercy of a bloodied, angry and violent mobocracy that cruelly punished them for well over 90 years.

Things have vastly changed for the millions of descendants from Southern slavery. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and many other pieces of legislation has ensured black people the opportunity to improve their lots and play a role in government, business and education. Still, the wounds of the Civil War have not totally healed. Integration has been a good thing but the Left’s long indulgence in racial favoritism continues to flame the passions of hate and bigotry. Black economist, Thomas Sowell, has documented this in several of his books.

Most Southern presidents did own at least a few slaves. Some were uncomfortable with that, but what would we have had them do? Free them? Where would they go? How would they live? Some other slave owner would have taken them as his possessions or maybe killed them. Judgements a 150 years after the fact are easily made and they are usually wrong.

Racial activists further alienate millions of white people from the hope of any peaceful unity. Destroying the monuments of Southern leaders from the Civil War and basically erasing their history, is an injustice to the people who had been honored, not for having slaves but for honorably, though perhaps foolishly, trying to protect a culture that was slowly dying out. To call them traitors, more than a century and a half after their defeat and humiliation, is ignoble and does not give proper respect to their valor. While the South had its deep flaws, it was the only home they had known. Acts of terror, violence and vandalism do nothing to ensure national unity but only prevent it from happening. They do not belong in a country that respects democratic choice and the rule of law. History also has a warning for us today. The word “Appeasement” had a prescient lesson for us. As it did not work in 1937 with Adolph Hitler, it will not work with BLM or Antifa. The more our government leaders cede to them, the more they will demand until there is no other option available but rampant violence.

This is not a defense of the Southern culture. Let the dead rest in peace. It is more a seriously attempt to ensure that people look through the objective of a historical lens that refuses to rush to a judgment on a historical fallacy, as well as racial, political or economic biases. As the Bible warns us, judge not lest ye be judged. To do otherwise is to risk the abuse of history and not its proper use.