If there is one issue of Catholic moral teaching that has wasted more time and energy of the faithful in the pews, it is the death penalty. Acceptance and approval of capital punishment within the Catholic Church has varied throughout history. After Vatican II, the Church became significantly more critical of the practice. In 2018, the Catechism of the Catholic Church was revised to read, in the light of the Gospel the death penalty is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person, and it now advocates for capital punishment to be abolished worldwide.

In past centuries, the teaching of the Church was generally accepting of capital punishment under the belief that it was a form of self-defense. The Church generally moved away from any explicit condoning or approval of the death penalty and adopted a more disapproving stance on the issue in the late sixties, when a more liberal viewpoint captured the religious imagination of many in the priesthood and hierarchy. It did not take very long for this change in Church teaching became more firmly entrenched in Catholic belief.

Modern Church figures such as St. John Paul II and Pope Francis, as well as the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, have actively advocated for the abolition of the death penalty. Pope John Paul II set the gold standard for this change in Church teachings with his 1995 encyclical, Evangelium Vitae, The Gospel of Life, when he stated that he believed that the death penalty was no longer necessary for a nation or a community to defend itself from murderers and other malefactors. The saintly pope felt that there were better means than capital punishment that would protect the innocent from the deadly hand of wanton killers. He appealed to the world to abolish a penalty that he believed was both cruel and unnecessary.

However, the pope failed to give sources or concrete reasons for his leaving millions less unprotected from the predators that prey on the innocent around the world. What about the need for self-defense in this country? Is that teaching no longer valid and if so, why? In making this blanket statement the pope did not give any indication as to what had changed in the course of history to justify his changing a long-standing teaching of the Catholic Church. I would like to know just what it was, other than the pontiff’s personal prejudice in favor of all human life, that warranted such a change.

The Pope’s views beg the question at which specific point in time, this new situation occurred, which in effect, repealed a teaching that had been with the Church for several hundred years. The pope never addressed the reasons why the death penalty had been accepted for several centuries. In fact, not only had the Church approved of the death penalty, it actively participated in it during the Inquisition. In Medieval Times, the Church had sanctioned the death penalty for heresy since false teachings jeopardized the eternal salvation of thousands of souls. It appears that the salvation of thousands of souls was more highly regarded than the lives of heretics.

I am, by no stretch of the imagination, advocating a return of the Inquisition, but only by point of historical contrast that I suspect that the modern Church has become more horizontal and much less vertical in its primary focus. To me that is a serious detour from traditional teachings and the fulfillment of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross so that all men may be saved. Is salvation no longer part of the Catholic equation or does the Church just assume, like its secular opposites, that all souls go to Heaven?

All I could envision was that Pope John Paul II was thinking of a mandatory life imprisonment without any chance of parole. Meanwhile convicted murderers are free to prey on the less violent or even the defenseless in the Darwinian setting that characterizes many prisons today. This does not surprise me because I have often read that most opponents of the death penalty are opposed to all punishment and would prefer that no one ever have to spend a day incarcerated. Pope Francis further underlined my viewpoint when he proposed the abolition of life imprisonment, which he felt is just a variation of the death penalty. Does the nose of the camel, not ring perfectly true here?

John Paul’s de facto revisionism ignores the possibility that a kinder and gentler judge or governor will not overturn or commute the mandatory sentence of the murderer. Prisoners can also escape or murder other prisoners, even guards. There is always solitary confinement. To restrict a murderer to solitary confinement for as many as 50years is as impractical as it is inhumane. It would not take the ACLU long to protest this as cruel and unusual punishment, providing little assurance that the murderer would not kill again. The Church’s apparently misguided confidence in the penitentiary system is further complicated by the fact that jailhouse lawyers have already convincingly argued that depriving their fellow prisoners of girlfriends, cable TV, Playboy Magazine and even peanut butter, violates the Eighth Amendment. With lethal injections, capital punishment is far more humane than it had been when the stake, rope, and guillotine had been standard means of dispatch.

In 1999, Pope John Paul II created a firestorm during his 31-hour papal visit to St. Louis. Never one to let political amenities thwart his divine mission, the Pope chastised Missouri for its overwhelming support of capital punishment. As a staunch defender of the unborn, I blanched at the substance of his remarks, at the TWA Dome, in front of 105-thousand faithful at Wednesday’s Mass. I feared his determined opposition to capital punishment would bifurcate the pro-life movement in Missouri. Helen Alvarre, who had known John Paul very well, said in a speech at St. Louis University the night before, that the pope’s early morning Mass, offered some candid insight into the pope’s thinking on this issue. With a well-spring of emotion, she said in simply English, the pope just did not want to see anyone die. For years, I have heard a number of priests echo this laudable sentiment. However, as valid as their feelings may be, a Church which bases it teachings on the subjectivity of feelings and emotion, and not reasons, will eventually evolve into a superstition.

Since the papal visit, St. Louis’ religious leaders have been on a crusade to strike the death penalty from the statute books. They have shown a unity of purpose, a spiritual fervor and a rhetorical dedication that have been noticeably absent in the abortion battle. Priests, who have virtually ignored abortion as a moral stain on the nation’s fabric, have been extremely vocal in sermonizing against the death penalty. Some interpret this as an unwritten declaration that opposition to abortion is a lost cause, relegating its many combatants to the sidelines in our increasing Culture of Death. Many pre-Vatican II Catholics, who had been raised on the morality of the death penalty, have been easily swayed by the Pope’s strong moral appeal. Others have had serious misgivings about the Pope’s apparent departure from the Church’s traditional teachings and have elected to respectfully dissent.

The Church, with its strong passion for social justice, seems to neglect criminal justice for depriving another human being of his inalienable right to life. When one is robbed, restitution must be made, if there is to be true forgiveness. While a murderer cannot resuscitate his victims’ lives, he should offer his own life up as repayment of the debt he owes, not only his victim but also society. Parenthetically, it is not a contradiction to say that capital punishment serves as a measure of value for innocent human life. A seven-year sentence for a capital crime just does not seem fair or equal.

The current definition of what it means to be pro-life in the Catholic Church is that all human life is sacred from the moment of conception to natural death. This term is a direct modification of the Church’s traditional teachings on the sanctity of human life. Many in the hierarchy remind us constantly that to be for the death penalty is to support an evil on a par with abortion. Of course, taken at its face value, this means that it would be morally wrong for Catholics to participate, even in just wars, since many people die unnaturally. This definition seems to disallow lethal force in order to defend one’s property and even one’s life. On its face value, it seems that Catholics have to become pacifists.

In my ethics textbook in college in 1965, there were three exceptions to the Commandment: Thou Shalt Not Kill, namely self-defense, a just war and the death penalty. Much of this reasoning can be extended to police officers in the line of duty who have killed to defend their own lives and the harm or death to innocent citizens. I suggest that the hierarchy add one important word to its teaching on life, namely innocent. Abortion and the death penalty do have one thing in common.

Of course this would then cause capital punishment to fall from the spectrum. Its opponents are never going to let that happen, no matter how much consternation they cause among the faithful in the pews. As it stands, the lives of people who have committed vicious and sadistic crimes are protected from any real legal justice. Abortion and capital punishment have innocence in common. Catholics need to be taught that abortion is a fatal assault on the innocent in the womb while the death penalty defends innocent life against sociopathic and nefarious murderers who have no respect for human life.

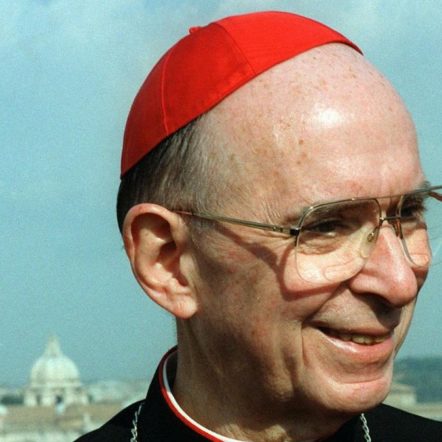

What happened to change this? Is the world all of a sudden a less dangerous place to live? No one in authority seems to want to answer this question. So I will make my own supposition, starting with Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, the late Archbishop of Chicago, who introduced Catholics to his Seamless Garment, or as it is now called, a Consistent Life Ethic. The Cardinal introduced this new dogma at a Fordham University speech in 1984. The Cardinal essentially provided a moral equivalency to many different life issues that has been expanded over the years. Now, for us to be true Followers of Christ, we have to follow a controversial list that includes not only abortion and euthanasia but also, capital punishment, nuclear disarmament, poverty, racial equality, the minimum wage, labor union support and health care for all. Not only does this clutter of diverse and debatable issues trivialize abortion and euthanasia, it conspires to destroy the inherent logic and meaning of the Consistent Life Ethic. One does not have to be a political aficionado to see the liberal bent of this list.

Shortly after the Cardinal proposed his change in Church teaching, many cynics harped that he was trying to protect his friends in the Democratic Party, who were hiding under the pro-choice mantle of New York Governor Mario Cuomo. It was Cuomo who established the perfect Catholic Politician Dodge when he said in front of thousands of receptive Notre Dame students, also in 1984, that while he was privately opposed to abortion but in my role as governor I must enforce the laws of the State of New York. Of course, Logic was of no concern to the Governor when he did his best to repeal the New York State Death Penalty Law, thus abrogating the will of his constituents in the Empire State. While the death penalty for the innocent unborn children remains through the moment of birth, the death penalty statue has disappeared from the state’s statutes.

As an aside, in 1996, when Cardinal Bernardin was on his death bed, suffering from cancer, he finally admitted that the rest of his garment issues were not to be equated with abortion and euthanasia. Apparently, no one listened to his deathbed confession because it did not fit their cultural agenda. Our current situation also underscores that few in the hierarchy were listening. It is my understanding that the late Cardinal’s pronouncement has permeated every aspect of the Respect Life Movement through the country. Also, from a popularity standpoint, the death penalty opponents seem to enjoy a strong and dedicated following, while those against abortion have been seriously compromised.

The Bernardinian garment emerged as an impenetrable shield for many Catholic leaders, clerics and lay people, who have placed the concerns of secular society and political power over the lives of unborn children and the traditional teachings of the Church. According to the erstwhile prefect of the Vatican’s highest court, and former St. Louis Archbishop, Raymond Burke, the Democratic Party risks transforming itself definitively into a party of death. Cardinal Burke’s prophesy is already a fact. Catholic President-elect, Joseph Biden, is a die-hard abortion advocate who promised to institutionalize Roe v. Wade through birth so that it would probably take a Constitutional amendment to dislodge it from from the Supreme Law of the Land.

There is another, more devious force at work that has undermined the traditional definition of the nature of man. The Church used to emphasize the Fall of Man in its teachings on original sin. That teaching seems to be collecting dust on musty shelves of the Vatican II Library. Professor Vincent Ruggiero painted a profound picture of how this happened in his essay for the Catholic Journal, The Source of Americans’ Hatred. The good professor answered his own question of just how modern society came to deny the perfectly reasonable and socially beneficial view that humans are by nature imperfect? His philosophical answer reverts to the thinking of the man who was largely responsible for the French Revolution and its perverse offspring, Socialism, Communism and the Progressive Movement. His name should be familiar to all— Jean Jacques Rousseau.

As the most familiar of the associative members of the French philosophes, though they differed on theological issues, Rousseau popularized the revolutionary idea that humans are born good and therefore society, rather than the individual, is responsible for what goes wrong in human behavior. Over a century later, Sigmund Freud and humanistic psychologists, such as Carl Rogers embraced Rousseau’s views and helped to remove any notions of sin, guilt and responsibility from the public’s consciousness.

This all segues to Sister Helen Prejean, a Catholic nun and one of the Sisters of Saint Joseph Medaille, based in New Orleans. She has become one of the most ardent advocates for the abolition of the death penalty. Her writings and speeches underscore the fact that she is an acolyte of the Seamless Garment. She is best known for her non-fiction book (1993) and its film adaptation, Dead Man Walking (1995), starring Sean Penn. The title of both versions comes from an old phrase in American prisons to designate men who had been sentenced to death. They were held on death row and were deprived of most social contact and barred from work or participation in prison programs. Prior to the 1960s, when guards would lead a condemned man down the prison hallway, prisoners would call out, Dead man walking! Dead man walking here!

The film tells the tale of Matthew Poncelet a character based on the convicted murderers of two men. After his final appeal had been denied, Poncelet asks Sister Helen to be his spiritual adviser through his execution. Sister Helen tells Poncelet that his redemption is possible only if he takes responsibility for what he did. Just before he is taken from his cell, Poncelet tearfully confesses to Sister Helen that along with his accomplice, he had killed the young couple and raped the girl. As he is prepared for execution, he appeals to the boy’s father for forgiveness and tells the girl’s parents that he hopes his death brings them peace. Poncelet is executed by lethal injection. and given a proper burial. The murdered boy’s father attends the funeral ceremony. Although he is still filled with hatred, he soon begins to pray with Sister Helen.

While undoubtedly Sister Prejean intended this film as a visual characterization of the inherent cruelty of capital punishment, I saw it in a different and more traditionally Catholic light. In a flashback, when confronting his dark sins, the audience experiences vicariously the vicious indifference of the two killers as they assault a young couple in coital embrace. They tie the couple up, but not before raping the young woman. Then, they turn their trembling victims over on their stomachs—naked, innocent, terrified and alone in a dark forest. Finally, the two killers shoot them unmercifully in the back of their heads.

Their murders stand in stark contrast to Poncelet’s execution. He has been able to make peace with God, the families of his victims, pray for forgiveness, enjoy a last meal, say farewell to his loved ones, and like the Good Thief on the Cross, next to Jesus, more than likely walk into paradise. The state may have justly ended his life, but Sister Prejean mercifully saved his soul. What could be a more Catholic movie than this!

To my way of thinking, the death-penalty scenario has not only conflicted my Catholic faith but has conspired to marginalize it. I am not an ardent supporter of the death penalty. I would never stand outside a prison and shout slogans, calling for the gruesome death of a convicted murderer. On the other hand, my societal understanding of the unmitigated violence of what I read in the daily newspapers, prompts me to think that nothing has changed in human nature to warrant the abolition of the death penalty. Without it, our society will be less protected than it has been under its aegis. I fear more innocent people will be sacrificed on the altar of Cardinal Bernardin’s Seamless Garment, which has nearly destroyed our reverence for innocent life.

Have we not reached the point of no return, where not only more innocent human beings will perish at the hand of the godless society we inhabit, and with them innocence itself? While I cannot answer this question, I am certain that one day— God will. As a nation and a Church, we may not like the answer.