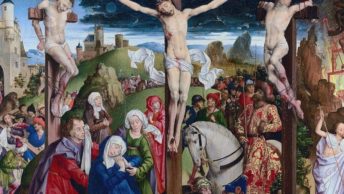

One of the most fundamental and ancient moral precepts is Do Good and Avoid Evil. It was expressed (in different words) in the Hippocratic Oath between the fifth and third centuries before Christ. More than a millennium later, St. Thomas Aquinas and others considered it a key ethical precept, as have most philosophers since then. The precept does not tell us what is good or evil, right or wrong, but simply encourages us to evaluate and learn from the experiences of life.

Through the ages, it was generally understood that good and evil are objective realities—that is, not subject to change but the same for everyone. Innumerable cultures have expressed this understanding by creating remarkably similar codes of behavior. These collected codes are known as the Tao. Here are some of them:

“Slander not” (Babylonian). “Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor” (Old Testament). “Utter not a word by which anyone could be wounded” (Hindu).“He whose heart is in the smallest degree set upon goodness will dislike no one” (Ancient Chinese). “Speak kindness . . . show good will” (Babylonian). “Men were brought into existence . . . that they might do good to one another” (Ancient Roman). “Love thy neighbor as thyself” (Old Testament). “Love thy wife studiously. Gladden her heart all thy life long” (Ancient Egyptian). “Be blameless to thy kindred. Take no vengeance even though they do thee wrong” (Old Norse). “Honor thy father and thy mother” (Old Testament). “Choose loss rather than shameful gains” (Ancient Greek). “The foundation of justice is good faith” (Ancient Roman). “One should never strike a woman, not even with a flower” (Hindu). “Love learning and if attacked be ready to die for the Good Way” (Ancient Chinese). “Death is better for every man than life with shame” (Anglo-Saxon).

These principles of behavior and innumerable others are the result of millennia of human experience. They have long been regarded as expressions of wisdom, revered among adults, and diligently taught to each new generation. This has been true of western culture as of other cultures. From time to time, the codes have been challenged, but they survived, as did the belief that humans are called to learn the difference between good and evil (right and wrong), and behave accordingly.

In our time, however, an age ironically considered by many to be more advanced than past ages, the moral precept of doing good and avoiding evil has morphed into a single concept—I call it WhateverMorality—which essentially casts aside the experiences and understandings of countless billions of human beings.

What does WhateverMorality actually mean? That goodness and evil are relative, a matter of personal decisions that no one else has any business questioning. In effect, this means that if Claude hates his neighbors but Harry loves his neighbors, both are right. Similarly, Bertha’s habit of getting even with others is neither worse nor better than her sister’s forgiving them; Susie’s shoplifting is as acceptable as paying Jim’s paying for the merchandise; and Clyde’s habit of drugging his dates so they cannot resist his sexual advances is neither criminal nor immoral but simply his preferred way of satisfying his urges.

WhateverMorality has led people to believe that whatever they say and do is GOOD merely because they say so. Similarly, EVIL is considered whatever a person believes it is, nothing more. Here are some examples of the consequences:

Good in education used to be defined as guiding students to develop language and mathematical skills and gain historical knowledge; in contrast, propagandizing them with sexual and political agendas was considered corrupting. Today many educators believe the former is passé and the latter is Good.

Good in immigration used to be defined as seeking permission to enter a country and waiting for approval; Evil, as breaking the law by entering without permission. Today many consider requiring permission inhumane and those who created or enforce such a law as immoral, while regarding those who enter the country without permission as blameless.

Good parenting historically included responsibility for children’s education, not only in the home but in the school as well; neglecting that responsibility was considered immoral and in some cases a crime. Today, however, many educators claim that they alone are responsible or what is taught in the classroom and parents are morally obligated to refrain from “interfering.”

Good in elected office traditionally meant providing for the safety of citizens, notably by funding police departments to prevent crime and arrest those who commit it. Today, many groups blame the police for crime and define Good as defunding and even eliminating police departments.

Good in the courts has always been associated with providing justice for victims of crime and appropriate penalties/punishments for perpetrators. Today, the focus has shifted to compassion for perpetrators through low bail, short (if any) sentences, and early parole, and nothing more than mild sympathy for victims.

But wait a minute. There is something very curious in all this. Those who embraced WhateverMorality did so because they believed traditional morality (the Tao) was rigid, intolerant, and divisive. In their view, everyone should create his/her personal morality—in other words, make whatever moral decisions he/she wished. This, they believed, would encourage everyone to respect other people’s individuality, the result of which would be greater tolerance and harmony. Unfortunately, that outcome never occurred. In fact, in the five cases mentioned above (and others), the reverse occurred. Each has led to an epidemic of insults, name calling, and accusations of everything from hating the country to deliberately causing chaos.

Even more curious is this: the most vocal advocates of tolerance and harmony have generally turned out to be the most intolerant and disharmonious! It seems their “Why can’t we all just get along” came with an addendum, “by agreeing with us.”

We could conclude that those people are hypocrites, but that judgment would be both rash and uncharitable. It is unlikely that they would have deliberately chosen to act in a way that both contradicted their own rationale and prevented their own goals from being realized. Surely, something else must be at fault, some flaw in their concept or misunderstanding of its consequences. But what might that something else be? And what could have caused it?

To be continued . . .

Copyright © 2022 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved