The imagination is the eye of the soul. –Joseph Joubert

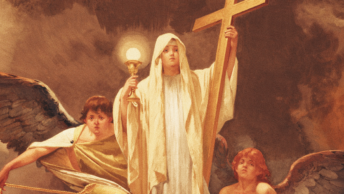

I think Catholic writers have a distinct advantage over atheists or people of other faiths. This is true because the Catholic Church has a 2000-year history that transcends the material universe. Its founder, Jesus Christ infused His earthly Church with a divine presence and an aura of mystery, reflected its sacraments, devotions, and doctrinal teachings.

When I was young most Catholics lived in an enchanted world of statues, holy water, stained glass windows, votive candles, saints and religious medals, rosary beads and holy cards. To add some devious spice to its mystical mixture, Catholics are often haunted by daily temptations from the Satanic Triad, namely the world, the flesh and the devil. This is the raw material of drama, comedy and tragedy.

But also in the mix the Church, even with its divine presence, remains a very human Church. Its popes, bishops and priests have been some of the most flagrant sinners in history. This apparent clash between the divine and the human is the stuff of great works of philosophical history, such as Saint Augustine’s The City of God.

St. Augustine was probably the first to recognize the warring tension between the City of God and the City of Man. It fell to man’s free will and God’s grace to determine which city they wanted to live in. This constant and simmering tension has been the dynamic that has provided the flawed human material for centuries of world-renown literature, poetry and passionate drama.

Ever since I was an adolescent, I was enthralled with the philosophical writings of Bishop Fulton J. Sheen. He enjoyed telling stories, or what we might construe as modern day parables that used many different kinds of metaphors to underscore the moral lesson of his stories.

Since then, metaphors that deal with Catholicism have been very real to me. The prophet Joel (3:1) proclaimed, Young men shall see visions and old men shall dream dreams. While I have long lost sight of young men’s visions, my dreams of heaven and the afterlife are more real than ever. They became almost tangible to me as I stood before the majesty of hope, despair and glory that Michelangelo captured in the Sistine Chapel. While its demonic images frighten me, the very act of being raised up to God’s waiting arms embraced me with a new sense of hope.

For 11 years (2003-2013), I was the feature writer the for the Cardinal Mindszenty Foundation Report. Unlike most academic historians who often write a dry kind of prose, I tend to craft innumerable lyrical metaphors and images in everything I write from plays and short stories to cultural essays for Mindszenty and my Gospel Truth blog posts, something I did for five years.

My experience has taught me that the fine line that separates non-fiction from fiction is little more than a blurred stroke. Or as Irish novelist Column McCann has profoundly phrased it the real that is imagined (from) the imagined that’s real.

Michelangelo has also inspired my writing style as well as my content. Most people do not realize he was primarily a sculptor, not a painter. One need only look at the power and physical majesty of his David to understand this. In every block of granite or marble in his studio Michelangelo envisioned a perfect statute just waiting to emerge.

For every article I wrote for the Mindszenty Foundation, I amassed all my notes and ideas into one block of stone for me to sculpt. I knew there was within my copious notes a beautiful verbal statue just beckoning to come out.

Probably the greatest work of fiction to come from a Catholic pen or quill was Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy whose cantos have immortalized in lyrical fashion the eschatology of the life to come—–Paradise, Purgatory or the Inferno. His Purgatorio intrigues most because of all of Catholicism’s moral teachings on death and judgment, this one makes the most sense. Since one has to be perfect to literally see the face of God and since virtually no one outside of the Holy family dies in that state of complete innocence, there is a metaphysical need to have a place of purification in the afterlife.

I have written about both Heaven and Purgatory in my blog, which I christened the Gospel Truth, a title just a bit presumptuous but dripping with the ironic boldness of Cervantes Don Quixote. In my posts I have tried to humanize Heaven by adopting some of the ideas I garnered from John Paul II’s book on the human body and its resurrection, Man and Woman: He Created them.

The pope celebrates the human body because it was created in the image and likeness of God. While the Pope is not technically writing fiction, he relies heavily on the allegorical imagery of the Bible, especially that of Genesis. His section on permissible nudity that is chaste, made me dream even more about the possibilities of Heaven.The Bible teaches that heaven will elevate the happiness and pleasures of this life exponentially.

While Jesus talked of many mansions that the Father had prepared, I have expanded it to Heaven being like a celestial vacation where we were free to walk about in our glorified bodies, sans any earthly attire and feel the brightness of His sun and the coolness of His ocean waters caress us like a loving Father.

I have often quipped that at my age my body gives me more pain and discomfort than any sort of pleasure. That was true until my wife and I started getting regular therapeutic massages. After several massages I was overwhelmed by the wholeness that her (masseuse’s) deep touch had returned to my entire body.

She explained my sensations were the result of the massive blood flow and what most massage therapists call the hormones of happiness. These transitory feelings I experienced from her magical fingers, palms and forearms gave me a brief glimpse of the emotional and physical harmony that must reign in Heaven. It has made me fear death less and look forward to Heaven with a greater enthusiasm.

It took awhile but it finally dawned on me! God wants me to be happy and to entice me to do His will he let me get a glimpse…just a glimpse of the life to come that was mine if I just would love him and those around me. In this case Lena’s firm touch was my heavenly connection. Massage therapy was a foretouch of heaven.

Lena also provided me with a stroke of metaphorical inspiration about Purgatory. I have been writing plays for nearly 10 years. To date I have written six–three of which were birthed locally, one that was stillborn and another that is still developing in the womb of my imagination.

The three produced plays were on Catholic themes that were based on my experience and very close to my heart. My mother died of Alzheimer’s disease in 2001. It was painful watching her decline for 12 years—seeing her personality, her faculties and her body deteriorate a little each day. Since I pride myself on a very good memory, watching her gradually lose her mind has haunted me ever since. To sublimate my fears I combined these feelings with my interest and expert knowledge of the moribund St. Louis Browns baseball team.

I created an Everyfan, who had lost the two most important things in his life—his wife and his team in the same year —1953. Some 25 years later he is losing his human legacy— the memories of both the Browns and his wife. I wanted to reconcile his declining memories with his Catholic faith. I called the play, the Last Memory of an Old Brownie Fan. Incidentally he prayed that his last thought would be of the lazy fly ball that signaled the end of the Browns’ 52-year history in St. Louis, which was also figuratively the end of his life on earth, as he knew it.

I have also been active in the pro-life movement for many years. So I followed up with two one-act plays—the one about abortion and the other about suicide. A Perfect Choice deals with the toughest argument pro-life advocates have to make—the life of the mother. I have seen good, religious men cave in when the choice would be the life of their wives or that of their unborn children. For research I reread Henry Morton Robinson’s classic novel, The Cardinal, which dealt with this dilemma in a graphic matter.

For my play I set up a reconciliatory scene between an estranged father and daughter 25 years after the father had told the doctors to save both of them when the doctor advised that he give permission to abort his second child. Unlike the book where the daughter survived, in my play both died and the five-year old held her dad responsible for the loss of her mother.

A Moment of Grace involves complete strangers, a man and a woman, who meet by chance in an elevator. They are both going up to the roof where independently of one another they plan to jump off the highest building in a small Midwestern college town. The elevator gets stuck and for the next 40 minutes they hash out their personal lives with regard to living and dying.

My work in progress brings me back to Lena’s massage table. I have been working on a play about Purgatory for several years. I first read Dante’s Purgatorio. The idea of being damned forever is a harrowing thought. I find it hard to accept that an infinitely merciful God, albeit a Just God could allow what might appear as billions of his human creations to suffer like that.

I had a Jesuit friend who told me two weeks after his ordination in 1969 that as Catholics we had to believe in the existence of Hell but we did not have to believe anyone but Lucifer and his band of recalcitrant angels were there. That’s why Purgatory makes so much sense to me.

Years ago I asked myself why did Purgatory have to have flames like Hell. Unlike traditional Catholic teaching, I wanted to create a Purgatory that was more rehabilitative than punitive. By that I envisioned a reformative purification that involved some discomfort but not just pain for punishment’s sake.

My first attempt had imagined a New York City subway car, like the ones I used to ride on the way to high school in New York City. My main character was sentenced to read the works of Charles Dickens. At first I called it For the Love of Dickens because despite his literary legacy, Dickens always bored me. My protagonist had to ride and endure the monotony of both the train and the dry reading of Dickens for as long as it took to get him to understand the mistakes of his sinful life. Then he could get off the purgatorial train.

To assist him in his redemptive quest were six other sinners, who got on and off the train to start and end a scene. Each one represented one of the remaining deadly sins. They had also been sentenced to read different books in order to enter Heaven. As a concept the idea was good but the characters, location and virtually everything else I wrote did not work. Riding a subway car and reading about people who do is really boring.

One afternoon Lena was making a very broad stroke down from my neck to the backs of my ankles. Every time she has done this I can feel her literally pushing the pain, and discomfort completely out of my entire body. One day it dawned on me that her heavenly touch was the perfect metaphor for a purgatorial experience that could not only dissolve human pain but just maybe the pain of the soul. I added to this my belief that at times I can feel her knitting the mystical strands of my body and soul together as God had intended.

In Western Civilization we have too often bifurcated the body and the soul. The Platonists have thoughtlessly separated them into an unconnected duality as if they were oil and water. The body and soul are a single unit.They must always be joined together or the body dies. That’s why John Paul II’s Theology of the Body and the resurrection of our bodies have been so important to a true eschatology.

As a result The Changing Room transformed my subway car into a massage spa. Gaby, the massage therapist spends much of eternity ministering to the integral connection of her people’s bodies and souls as the final stage before their eventual assents to Heaven.

Her three people included a Lothario with an itch to scratch, a masculine woman with a love-hate relationship with her father and a shy, lonely old man who has never been loved. Her magical fingers and talkative personality force a dual spiritual and physical purging that will make her people worthy of seeing the face of God for eternity. What more could any of us hope and pray for?

But this and my last two attempts to capture the lucky magic I had for my three published plays had forsaken me. The play failed to resonate with the members of the local theatrical community for whom I had several readings. But I am thankful for what I was able to do with my plays, essential all with Catholic themes, that maybe some day after I am gone, my first three plays and hopefully the last one will resonate with someone and see the stage once more.