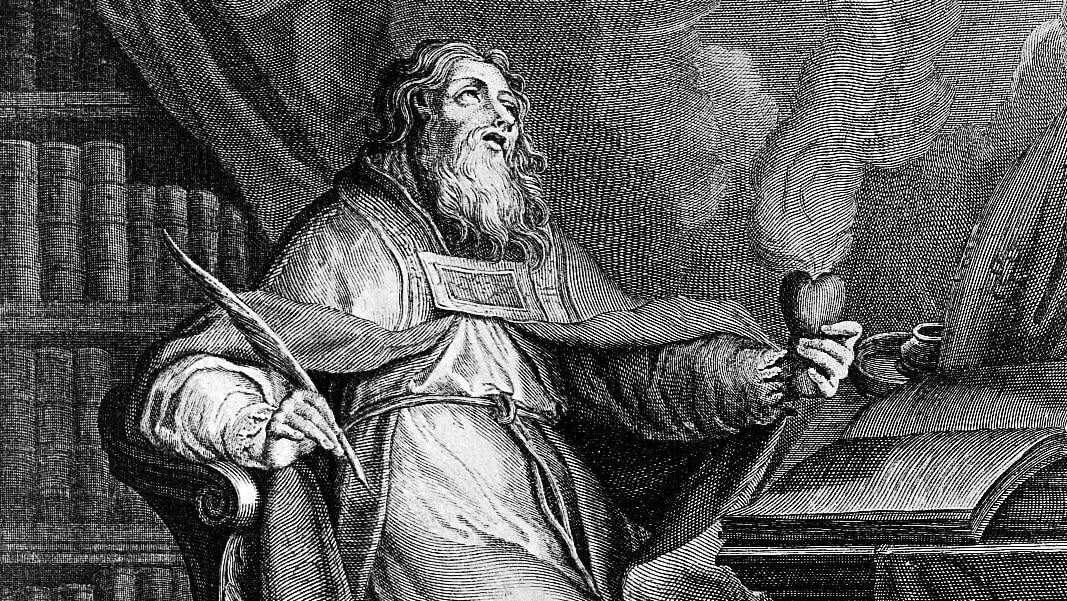

On Friday, October 18th, I had the joy of attending an interesting lecture given by Rev. Prof. Salvino Caruana OSA on the Confessions of St. Augustine. In this very intriguing lecture, I learned the four characteristics which make up the Confessions as written by the great bishop of Hippo.

To begin with, the Confessions revolve around the fact of portraying the greatness and power of God. In other words, they are confessio laudis. The opening part of Book One is really impressive:

“Great art you, O Lord, and greatly to be praised; great is your power, and infinite is your wisdom.” [Cf. Ps. 145:3 and Ps. 147:5] And man desires to praise you, for he is a part of your creation; he bears his mortality about with him and carries the evidence of his sin and the proof that you do resist the proud. Still he desires to praise you, this man who is only a small part of your creation. You have prompted him, that he should delight to praise you, for you have made us for yourself and restless is our heart until it comes to rest in you. (Book 1.1.1).

God’s greatness, power and infinite wisdom move Augustine to see the hidden desire of the human being to praise Him. It seems that man cannot not praise God since he is an integral part of his creation. Even if in man there is the tendency to sin, he still wants to praise God. And when he does praise God, he does it because God impels him to do so! What a great demonstration of Augustine’s constant belief and teaching that we do good only because we are guided by God’s grace and nothing more!

The second aspect of the Confessions nature is that in these confessions are, moreover, confessions of sins or confessio peccati. This is clearly alluded to when one is able to recognize the greatness of his guilt before the greatness of the love and mercy of God. (see Psalm 31,5) The fact that Augustine confesses himself as a great sinner, he is at the same time, according to the Scriptures, already acknowledging God’s mercy in his life.

“Suppose we are immortal and live in the enjoyment of perpetual bodily pleasure, and that without any fear of losing it–why, then, should we not be happy, or why should we search for anything else?” I did not know that this was in fact the root of my misery: that I was so fallen and blinded that I could not discern the light of virtue and of beauty which must be embraced for its own sake, which the eye of flesh cannot see, and only the inner vision can see. (Book 6.16.26)

Thus the soul commits fornication when she is turned from you, and seeks apart from you what she cannot find pure and untainted until she returns to you. All things thus imitate you–but pervertedly–when they separate themselves far from you and raise themselves up against you. But, even in this act of perverse imitation, they acknowledge you to be the Creator of all nature, and recognize that there is no place whither they can altogether separate themselves from you. (2.6.14)

But while he was speaking, you, O Lord, turned me toward myself, taking me from behind my back, where I had put myself while unwilling to exercise self-scrutiny. And now you didst set me face to face with myself, that I might see how ugly I was, and how crooked and sordid, bespotted and ulcerous. And I looked and I loathed myself; but whither to fly from myself I could not discover. And if I sought to turn my gaze away from myself, he would continue his narrative, and you wouldst oppose me to myself and thrust me before my own eyes that I might discover my iniquity and hate it. (8.7.16)

The third aspect that emerges from the Confessions of St. Augustine is that they are a profession of faith, or confessio fidei. This confession of faith comes from Augustine’s confession of his own ignorance as to how to begin to praise God for all He has done in his life.

Grant me, O Lord, to know and understand whether first to invoke you or to praise you; whether first to know you or call upon you. But who can invoke you, knowing you not? For he who knows you not may invoke you as another than you art. It may be that we should invoke you in order that we may come to know you. But “how shall they call on him in whom they have not believed? Or how shall they believe without a preacher?” [Rom. 10:14 ]. Now, “they shall praise the Lord who seek him,” [Ps. 22:26] for “those who seek shall find him,” [Matt. 7:7] and, finding him, shall praise him. I will seek you, O Lord, and call upon you. I call upon you, O Lord, in my faith which you have given me, which you have inspired in me through the humanity of your Son, and through the ministry of your preacher. (1.1.1)

Finally, the Confessions are themselves a confession or declaration of the weakness of the human will. In other words, they are a confessio infirmitatis. This can be seen particularly in Book Seven wherein Augustine confesses how he was subjugated by the reality of sin.

For in my struggle to solve the rest of my difficulties, I now assumed henceforth as settled truth that the incorruptible must be superior to the corruptible, and I did acknowledge that you, whatever you art, art incorruptible. For there never yet was, nor will be, a soul able to conceive of anything better than you, who art the highest and best good. And since most truly and certainly the incorruptible is to be placed above the corruptible–as I now admit it–it followed that I could rise in my thoughts to something better than my God, if you wert not incorruptible. When, therefore, I saw that the incorruptible was to be preferred to the corruptible, I saw then where I ought to seek you, and where I should look for the source of evil: that is, the corruption by which your substance can in no way be profaned. For it is obvious that corruption in no way injures our God, by no inclination, by no necessity, by no unforeseen chance–because he is our God, and what he wills is good, and he himself is that good. But to be corrupted is not good. Nor art you compelled to do anything against your will, since your will is not greater than your power. But it would have to be greater if you yourself wert greater than yourself–for the will and power of God are God himself. And what can take you by surprise, since you knowest all, and there is no sort of nature but you knowest it? And what more should we say about why that substance which God is cannot be corrupted; because if this were so it could not be God? (7.4.6).

This swift journey into the four elements that constitute St. Augustine’s Confessions make me realize more that the Confessions are surely not to be read as an autobiography. More than that, they can be read and appreciated as Augustine’s intentional enterprise, within the remit of God’s permissive felt presence, to remember those central events and experiences in which he can now recognize as well as celebrate the mysterious actions of God’s prevenient and provident grace.

As Pope Benedict XVI magnificently explained in his catechesis of Wednesday, January 9th, 2008, the Confessions are an “attention to the spiritual life, to the mystery of the ‘I’, to the mystery of God who is concealed in the ‘I’. [This] is something quite extraordinary, without precedent, and remains for ever, as it were, a spiritual ‘peak.’”