The gift of faith includes mystery, which is so necessary when seeking God in positive or negative life situations. To focus on the light of God’s truth and the hope of heaven while walking through the shadows is an enormous blessing. Faith reassures us that God is with us even when we walk through a seemingly trackless wasteland. When we are out of sorts for one reason or another, there is peace in the fact that this shall pass. Faith is an energizer that strives to uniquely reflect the image and likeness of God in all of life’s circumstances. When we ponder his love and mercy, how little we know! Thinking about his greatness and majesty keeps the concerns of life in their proper perspective.

In divine faith, the one believed is God. In human faith, the ones believed are persons. It is sometimes challenging to accept the word of another in honesty and in truth. Thomas Aquinas wrote: Someone may object that it is foolish to believe what he cannot see. . . . Yet, life in this world would be altogether impossible if we were to believe only what we can see. How can we live without believing others? How is a man to believe that his father is so and so? Hence man finds it necessary to believe others in matters that he cannot know perfectly on his own.

Faith and its necessary sacrifices are an essential part of love within families, between friends and in the Church. As trust and faith in God is strengthened, it increases trust and faith in others (within reason). It provides a foundation for accepting others, which includes those we do not understand (our children) or others (our neighbor, supervisor or in law).

A life of faith can be ignited from a small grace such as a quiet reading of the Twenty Third Psalm, a beautiful sunset or something someone said. On rare occasions, it can be ignited by an extraordinary occurrence and lead to unimaginable places. In the beginning of his book, The Waters of Siloe, Thomas Merton relates this story:

It is late at night. Most of the Paris cafes have closed their doors and pulled down their shutters and locked them to the sidewalk. Lights are reflected brightly in the wet, empty pavement. A taxi stops to let off a passenger and moves away again, its red tail light disappearing around the corner.

The man who has just alighted follows a bellboy through the whirling door into the lobby of one of the big Paris hotels. His suitcase is bright with labels that spell out the names of hotels that existed in the big European cities before World War II. But the man is not a tourist. You can see that he is a businessman, and an important one. This is not the kind of hotel that is patronized by mere voyageurs de commerce. He is a Frenchman, and he walks through the lobby like a man who is used to stopping at the best hotels. He pauses for a moment, fumbling for some change, and the bellboy goes ahead of him to the elevator.

The traveler is suddenly aware that someone is looking at him. He turns around. It is a woman, and to his astonishment she is dressed in the habit of a nun. If he knew anything about the habits worn by the different religious orders, he would recognize the white cloak and brown robe as belonging to the Discalced Carmelites. But what on earth would a man in his position know about Discalced Carmelites? He is far too important and too busy to worry his head about nuns and religious orders—or about churches for that matter, although he occasionally goes to Mass as a matter of form.

The most surprising thing of all is that the nun is smiling, and she is smiling at him. She is a young sister, with a bright, intelligent French face, full of the candor of a child, full of good sense, and her smile is a smile of frank, undisguised friendship. The traveler instinctively brings his hand to his hat, then turns away and hastens to the desk, assuring himself that he does not know any nuns. As he is signing the register he cannot help glancing back over his shoulder. The nun is gone. Putting down the pen, he asks the clerk, Who was that nun that just passed by? I beg your pardon monsieur. What was that you said? That nun, who was she anyway? The one that just went by and smiled at me. The clerk arches his eyebrows. You are mistaken, monsieur. A nun, in a hotel, at this time of night? Nuns dont go wandering around town, smiling at men! I know they dont. That is why I would like you to explain the fact that one came up and smiled at me just now, here in this lobby. The clerk shrugs: Monsieur, you are the only person that has come in or gone out in the last half hour.

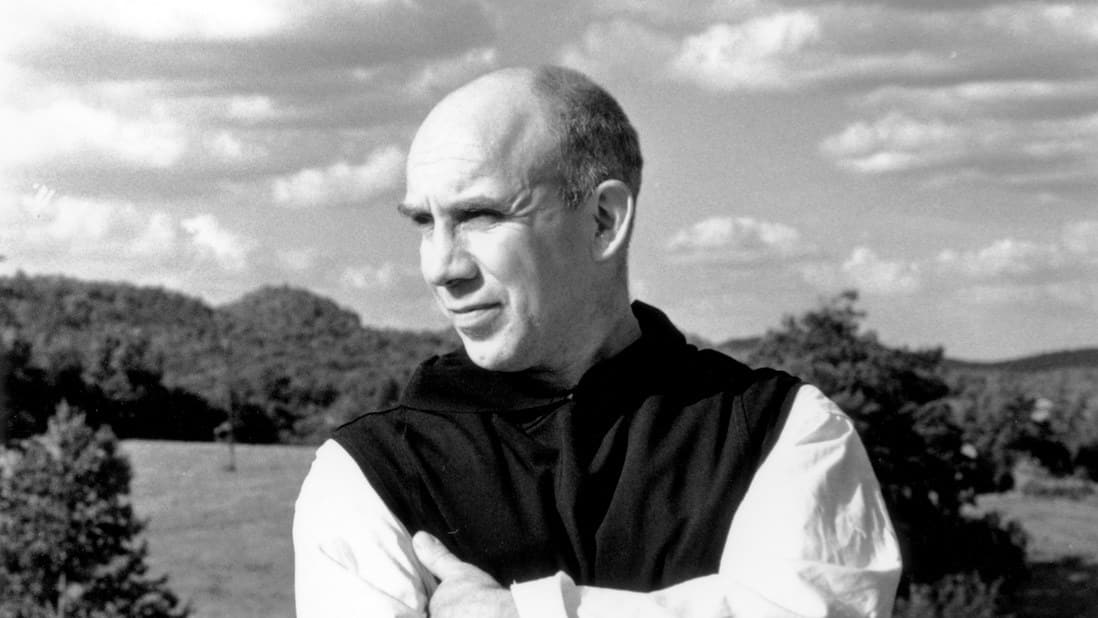

Not long after, the traveler who saw that nun in the Paris hotel was no longer an important French industrialist, and he did know something about religious habits. In fact, he was wearing one. It was brown: a brown robe, with a brown scapular over it, and a thick leather belt buckled about the waist. His head was shaved and he had grown a beard. And he wore a grimy apron to protect his robe from axle grease. He was lying on his back underneath a partly disemboweled tractor. There was a wrench in his hand and black smudges all around his eyes where he had been wiping the sweat with the back of his greasy hands. He was a lay brother in the most strictly enclosed, the poorest, the most laborious, and one of the most austere orders in the Church. He had become a Trappist in a southern French abbey. (pp. 13-14)