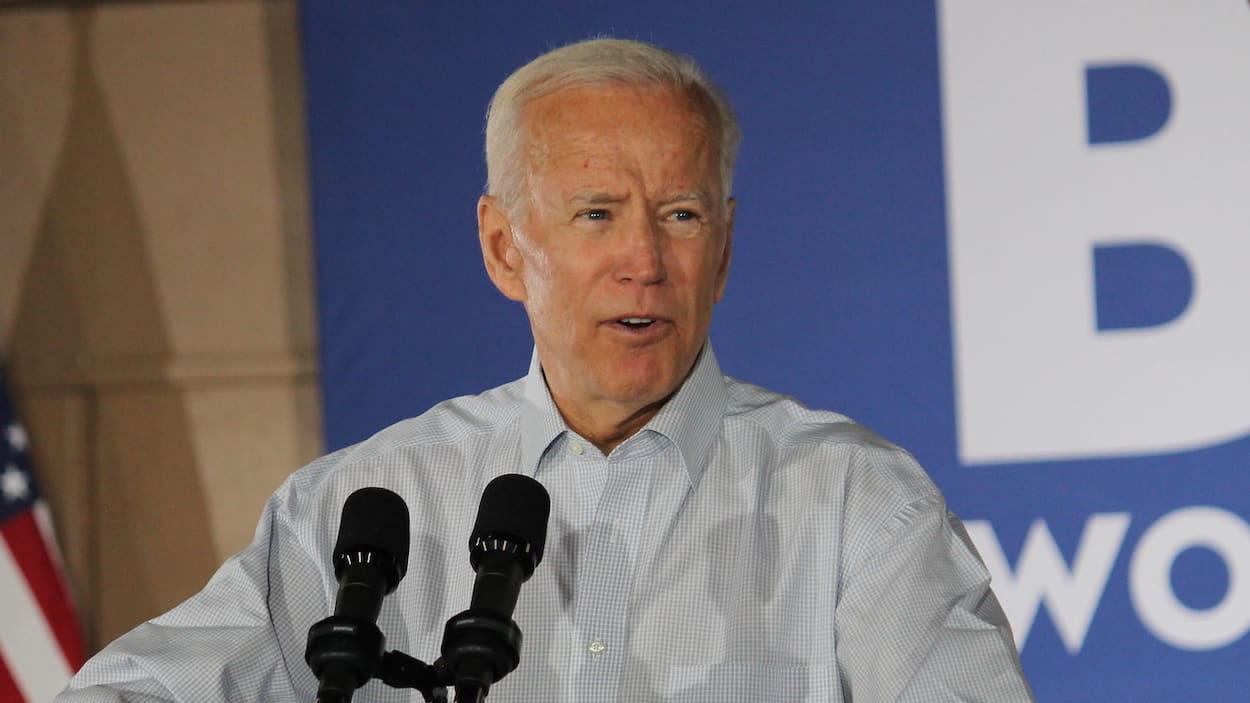

Part 1 of this essay argued that the denial of communion to Joe Biden was appropriate and objections to that denial were based on two false ideas—that the Catholic view of abortion is unreasonable, and that when elected officials support the Catholic view they are “imposing” it on others. The essay ended with the assertion that, ironically, the Catholic Church itself is responsible for those ideas and for the lamentable consequences they produced.

To understand how the false ideas about Catholic teaching and the conduct of elected officials came about, it is necessary to recall some key events from the late 1940s through the 1960s. At the beginning of that period the Church’s position on both contraception and abortion was firm and unyielding—both were considered grievous, “mortal” sins. Then in 1948 and 1953 Alfred Kinsey published, respectively, Sexual behavior in the Human Male and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female, which were quickly accepted as definitive scientific proof that all forms of sexuality are normal and morally acceptable.

During the same period, psychologists Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow advanced the view that truth and reality are subjective and that morality is whatever people believe and/or wish it to be. Through widespread media publicity and “encounter groups” their ideas became influential in Catholic religious orders as well as in the general culture. Decades later, Kinsey’s claims were exposed as fraudulent and Rogers’ and Maslow’s premises were found to be deeply flawed. But until that development, traditional morality was greatly disparaged.

In 1958 the new pontiff, John XXIII, declared, “I want to throw open the windows of the Church so that we can see out and the people can see in.” A number of theologians who shared Pope John’s view worked to make the Church less authoritarian and more hospitable to the changing culture. Among them was John Courtney Murray, S.J. who argued for a more positive attitude toward religious freedom.

A leading prelate, Richard Cardinal Cushing, was strongly influenced by Murray’s writings. A close friend of the Kennedys, Cushing officiated at JFK’s wedding, baptized Kennedy children, and delivered the invocation at the inauguration in 1961.

For years Cardinal Cushing had believed that contraception was a grave sin, and he supported laws banning it. In 1948 he said in a radio statement that contraception was “anti-social and anti-patriotic, as well as absolutely immoral,” and “still against God’s law.” Fourteen years later he repeated that view. On June 1962, in The Pilot, the Boston Archdiocese’s official newspaper, Cushing wrote, “Every method of contraception which interferes with the progress of marital activity towards its natural goal of conception is intrinsically wrong and in violation of the natural law.”

Four months after Cushing made that statement, the Second Vatican Council opened in Rome. One of the most publicized issues to be discussed at the Council was contraception, and expectation was high that the Church would take a major step in changing its view by approving the birth control pill. Clerics in general and prelates in particular were uncertain what the outcome of the lengthy hearings and deliberations would be when the Council ended. No prelate wanted to be caught unprepared for the change in moral theology that seemed so likely.

Midway through the Council, Cardinal Cushing changed his thinking on the contraception issue. Whether he did so because he anticipated a change from Rome or because of his commitment to religious freedom, or both, is not known. In any case, in 1963, on WEEI radio, he stated, “I have no right to impose my thinking, which is rooted in religious thought, on those who do not think as I do.” (Emphasis added.) Following that meeting, he approved a meeting between diocesan representatives and Planned Parenthood to prepare a statement urging the repeal of the law banning contraception.

From that time on, the Cardinal repeated his conviction that Catholic views on contraception should not be imposed on others. For example, On March 2 1965 at a legislative panel, he offered a written statement that Catholics “do not seek to impose by law their moral views on other members of society.” Vatican 2 ended without changing Catholic teaching on contraception but instead reinforcing it with the publication of Humane Vitae. For a growing number of Catholics, however, contraception was no longer an issue—they had already decided in its favor. Meanwhile, Planned Parenthood and radical feminists declared victory on the contraception issue and turned their attention to their next goal, legalizing abortion.

Soon Catholic politicians sought a way to escape Planned Parenthood’s depiction of them as unsupportive of “women’s rights over their bodies.” They found the perfect solution in Cushing’s refusal to impose his personal beliefs on others. This permitted them to stand with the Church in opposing abortion yet simultaneously support the pro-abortion lobby, and thus win votes from both sides of the issue.

Over the next few decades—especially after the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973—many Catholic politicians embraced the Cushing principle. The most dramatic example of the shift from pro-life to pro-abortion was that of Ted Kennedy, who served in the U.S. Senate from 1962 to 2009. In 1971 he wrote this to a constituent:

“Wanted or unwanted, I believe that human life, even at its earliest stages, has certain rights which must be recognized—the right to be born, the right to love, the right to grow old. . . . When history looks back to this era, it should recognize this generation as one which cared about human beings enough . . . to fulfill its responsibility to its children from the very moment of conception.”

By the time Roe v. Wade was decided twelve years later, Kennedy had completely reversed his position and spent the rest of his career as the foremost political champion of abortion “rights.”

Less dramatic than Kennedy’s example, but little different in other respects, are the examples of Joe Biden who began his political career in 1972, Dick Durbin, who has served in Congress since 1982, John Kerry who has served in Congress and other federal positions since 1982. All four, among many other politicians, accepted the Cushing rejection of imposing one’s views as their mantra.

By the 1980s the Cushing principle was firmly established as Catholic politicians’ default response to the abortion issue. It therefore needed no reinforcement. Nevertheless, New York Governor Mario Cuomo, a Democrat, provided reinforcement in an address at Notre Dame entitled “Religious Belief and Public Morality: A Catholic Governor’s Perspective.”

Cuomo’s address referenced abortion 71 times but contraception only 7, thereby underscoring the extent to which the focus of political debate had shifted. To his credit, Cuomo noted that the Constitution affirms the right to attempt persuading fellow citizens to adopt one’s point of view. But then, following Cushing, he warned about “the price of seeking to force our beliefs on others.” In addition, he flatly declared that banning “abortion by either the federal government or the individual states . . . wouldn’t work . . . [thus] creating a disrespect for law in general,” adding that rather than trying to ban abortion, we should seek to find “a consensus view of right and wrong.”

For Catholic politicians, the takeaway from Cuomo’s address was, You are free to argue for any position you want, as long as it’s directed toward some consensus other than banning abortion. Two years after Cuomo’s address, 77% of Democrat Senators were reportedly pro-abortion, while no Republicans were. And in the House, 52% of percent of Democrat Representatives were pro-abortion, while10% of Republicans were. (Crisis Magazine, December 1, 1988)

As I explained in Part 1, the notion that expressing one’s convictions on an issue constitutes imposing them on others is not merely false but absurd, especially in a democratic society in which free speech is a guaranteed right and meaningful debate is necessary for efficacious government. Nevertheless, Cardinal Cushing—one of the most influential prelates of the Catholic Church in America—not only embraced the absurd notion himself, but encouraged others to do the same.

That Cardinal Cushing believed he was serving his Church and his nation I have no doubt. But his good intentions do not change the consequences that followed. Consider the legacy of the Cushing principle:

- For more than half a century, Catholic elected officials have been encouraged, and in many cases felt obligated, to keep their convictions out of their public discourse, especially in state legislatures, the U.S. Senate, and the House of Representatives—while Protestants, Jews, Muslims, agnostics, and atheists took the natural and more intelligent path of vigorously expressing their convictions.

- As a result, traditional Catholic thought has been largely absent from American politics, particularly in the case of controversial issues like abortion. This absence not only left the public uninformed about the Catholic perspective, it also changed the thought patterns of Catholic officials. Refraining from expressing their beliefs led to no longer thinking of them; hearing opposing views brought familiarity with them; and familiarity with those views led to embracing them. That progression explains why many Catholic politicians now seem more comfortable with Planned Parenthood’s arguments for abortion than with the Church’s arguments against it.

- The absence of Catholic thought in government has contributed significantly to the lamentable success of abortion advocates. There have been over 60 million abortions in the U.S. since Roe v. Wade was decided. (Without the courageous stand of Evangelicals and other conservative Protestants in defending unborn life, there would no doubt have been many more.)

- The abortion of 60 million innocent human beings has meant the loss to our country of inestimable God-given talent in medicine, law, education, religion, the arts, business, government, and all other fields of endeavor. It has meant, as well, the loss oftechnological inventions, solutions for environmental problems, cures for disease, and tax income to feed the hungry and homeless and care for the elderly and the ill.

Imagine for a moment how different the legacy might have been if, instead of saying “I have no right to impose my thinking, which is rooted in religious thought, on those who do not think as I do” and “[Catholics should not] forbid in civil law a practice that can be considered a matter of private morality,” Cardinal Cushing had said this:

“Catholic politicians not only have a right to voice their religious and philosophic beliefs, but also a moral obligation to do so. Others have that same right and obligation. And both should use the democratic process to resolve their differences for the benefit of all Americans.”

This statement would have made the point that I believe Cushing intended—that no one need fear that American Catholics will put loyalty to Rome above loyalty to country—but without encouraging elected officials to abdicate their responsibility, abandon their own convictions on important issues, and defer to those with opposing beliefs.

Cardinal Cushing was a good man who made a grievous error that has unfortunately done immeasurable harm. He bears responsibility for that error. So do the prelates and theologians who realized that the Cushing principle was erroneous yet chose to remain silent rather than publicly challenge it, and the Catholic elected officials who were guided by Cushing’s example. The degree of culpability (moral accountability), of course, varies widely, but this much is clear—it is significantly diminished in the case of elected officials whose consciences were quieted by the actual or tacit approval of their spiritual advisors.

Can the Church do anything to correct its error and overcome the social harm that error has caused? I am convinced that it can and I will pursue that subject in Part 3.

Copyright © 2019 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved