The recent commemoration of the Holocaust brought into my heart and mind the reality of suffering. One of the most complex subjects in Judaism is certainly suffering. There are a myriad of approaches in Judaism in order to try to understand this great, actual and challenging problem of suffering.

To begin with, suffering is certainly a scandalous approach. In fact, its complexity arises not merely due to the many ideas that already exist under the sun concerning this human phenomenon in Judaism. Rather, and mainly, the topic of suffering is, essentially, scandalous. In his article on suffering in the Encylopedia Judaica, Steven S. Schwarzschild could not explain it much better when he wrote that “if God were good, He would not want His creatures to suffer, and if, all powerful, He would be able to prevent their suffering.” Sure! If God is good He certainly protects His children from suffering! But the world, and particularly, Jewish history, show otherwise! How many times the Jews were persecuted and crushed by their enemies! The Holocaust is a case par excellence!

Even the Bible voices the same concern regarding the subject of suffering. For the Bible suffering is an existential human component. After Adam had sinned God stipulated that suffering now has become part and parcel of his earthly existence. In the sweat of your face you shall eat bread till you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; you are dust, and to dust you shall return (Gen 3:19). Likewise, in the Book of Job, Eliphaz the Temanite thus answered to Job: But man is born to trouble as the sparks fly upward (Job 5:7).

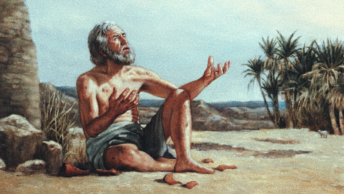

The book of Job is precisely and entirely dedicated to the problem of why do righteous people suffer. We know that, according to the principle of retribution, in this world, good people should be blessed whereas the wicked ones are to be severly punished for their sinful deeds. But if Job was righteous why should he be invaded by all this tragedy? In his suffering, “Job protests with all his energy and his most cutting irony against the orthodox dogma of retribution impersonated by his three friends”, namely Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite, and Zophar the Naamathite. And, the more these friends stress that he must have sinned Job not only emphasized his innocence but also doubts God’s justice. Finally, God speaks to Job from a whirlwind.

As Rabbi Jack Abramowitz explained, “the main lesson of the Book of Job is that God’s management of the world is not the same as a human’s management of his own affairs… We say that God ‘manages’ the universe because it is a concept we can understand but we must not trick ourselves into thinking that it in any way resembles human management. Job (the Book) teaches us that we must have faith and not delude ourselves into thinking that God is like one of us. With this understanding, misfortunes become easier for one to bear. Quite the opposite, one’s love for God will only increase, as Job’s did once he understood things for himself (see 42:5-6, cited above)”.

Furthermore, as Ethan Dor-Shav rightly suggests, “in his final words Job takes solace in the existential human condition, understanding its potential for divinity despite the impermanence and suffering of earthly life. Job does not rest his case, but he does rest. He no longer wants to rebel or to die. Many of his questions are unresolved. Details of his revelations are obscure. The reason for this is that Job’s prophecy is intended for his ears alone. The reader must pose his own questions to God and hear his own replies. All we are taught is that direct, personal communication with the divine is possible. When Job achieved it, he and God began with a clean slate. The new, knowing Job now re-states his inquiries using the future tense.”

The great life lesson is that even if we humans, as finite as Job was, cannot comprehend God’s ways, however, notwithstanding the suffering we go through, if we communicate with God we can move on no matter what. And, in case we tend to forget this important teaching, let us simply remind ourselves of the infinite mysteries of the universe which are, by far, much greater than our tiny suffering situation. To put it philosophically, the more we lose ourselves in God’s infinity the more we can live in peace and thrive amid our suffering finitude.

From the area of Jewish mysticism, Kaballah (in Hebrew: קַבָּלָה, literally means “reception, tradition” or “correspondence”), which is pratically an esoteric method, discipline and school of life, holds that “suffering … is a natural and vital part of life that needs to be recognized for what it is and subsequently handled correctly. Suffering, in the view of the Kabbalah, has to do primarily with responsibility and spiritual growth. We all need to take on responsibility in our life and carry the important things forward, whether we have made the personal decision to do so or we have undertaken it on behalf of another.”

Let us also add that responsibility in suffering is not just for the self but also for those who are suffering around us. As a matter of fact, Judaism reminds us that we are to show active smpathy to those who are suffering too. Compassion for the suffering of others is essential because “‘The poor are God’s people,’ and they exist so that others may help others out of their poverty (BB 10a). Man is admonished to share in the suffering of the community and not enjoy himself while others are suffering (Ta’an. 11a).”

Jewish philosophers have also grappled with the problem of suffering. Contrary to the Jewish Dutch philosopher of Sephardi origin, Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677), who upheld that suffering simply does not exist another Sephardic Jewish philosopher, this time hailing from the apex of the Middle Ages, Moses ben Maimon, commonly known as Maimonides (1138–1204), said that “God’s created world is thoroughly good.” Therefore, “God cannot have created evil in any of its forms.” If that is the case how can we explain the existence of evil? For Maimonides, “evil is privation, and privation, being not a thing but the absence of some thing or quality, is not created.”

For Maimonides there are three kinds of evil: “(l) The first kind of evil is that which is caused to man by tie circumstance that he is subject to genesis and destruction, or that he possesses a body… (2) The second class of evils comprises such evils as people cause to each other, when, e.g., some of them use their strength against others. These evils are more numerous than those of the first kind; their causes are numerous and known; they likewise originate in ourselves, though the sufferer himself cannot avert them… (3) The third class of evils comprises those which every one causes to himself by his own action. This is the largest class, and is far more numerous than the second class. It is especially of these evils that all men complain, only few men are found that do not sin against themselves by this kind of evil.”

In Maimonides’ view God is in no way responsible for these evils together with their concomitant sufferings. Furthermore, all these evils are brought about by basic natural forces, human faults, or simply by human ignorance.

But if God is not responsible for the evil that people cause to each other why did He allow the Jewish people to be brutally exterminated in the Nazi concentration camps? Personally the best example I found in order to have a sort of an answer to this riddling question is that given by the German-born Dutch-Jewish diarist Annelies Marie “Anne” Frank (1929-1945). In her famous diary she also dealt with the Jews and their relationship with the suffering they had to endure throughout their history, particularly in World War II. She wrote: “In the eyes of the world, we’re doomed, but if, after all this suffering, there are still Jews left, the Jewish people will be held up as an example.”

Hence, rather than succumbing to the fatalism of reproaching God for inflicting suffering on his chosen people, as did Abraham, Job, Honi ha-Me’aggel and Levi Isaac of Berdinchev, or even Richard Rubenstein’s (1924-) position that because “the terms of the covenant cannot be amended [and] since the Holocaust contradicted the covenantal reality, we can only deduce [that] God must be dead,” Frank opted for the Talmudic interpretations of suffering as “afflictions of love” (yissurin shel ahavah). Now suffering becomes the final way of divine purification which leads to unio mystica. Even if that meant that, as Ignaz Maybaum would suggest, that the Jews were like the suffering servant of Isaiah 53 who would suffer vicariously for the wickedness of others.”

In his book The Face of God after Auschwitz Ignaz Maybaum (1897-1976) writes: “The Golgotha of modern mankind is Auschwitz. The cross, the Roman gallows, was replaced by the gas chamber. The gentiles, it seems, must first be terrified by the blood of the sacrificed scapegoat to have the mercy of God revealed to them and become converted, become baptized gentiles, become Christians.” The six million Jews had to be sacrificed so that the Christian world comes to understand that spiritual progress is, in fact, possible without death. In this way, God could arouse the Christians’ religious consciousness to live up to their confessed ideals through a language they are familiar with, suffering. But can God, through suffering, convey to us his divine message?

The debate as to why we suffer goes on. According to Yakoov Weiland there are 5 possible reasons as to why we suffer: “(1) to strengthen our faith and acceptance of G-d’s will; (2) to help us grow and improve; (3) to help others, by giving them the opportunity to be kind, appreciate their blessings, and learn from our example; (4) to send us a spiritual wakeup call and to cleanse unrepentant sins; [and] (5) to refine and elevate our souls”.

If, as Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786) said, “suffering reinforces a person’s powers”, and suffering is, as Rabbi Asher Resnik put it, a choice, then one is invited to search for its meaning. I think that only in meeting God can one really live peacefully with the reality of suffering. It is only in the encounter with God that one can wisely discern what Rabbi Asher Resnick tells us, namely that “pain is a reality, suffering is a choice.” A choice that opens us to abandon ourselves in God’s hands through the language of prayer!

Save me, O God! For the waters have come up to my neck (Ps.69:1)!