America is on fire. Protestors are burning flags. Rioters are burning cars. And people are metaphorically burning bridges, rendering it impossible to speak across the chasm of political difference.

It’s time to pause in burning down our national house. As the Talking Heads warn in their iconic song, “Watch out. You might get what you asked for.”

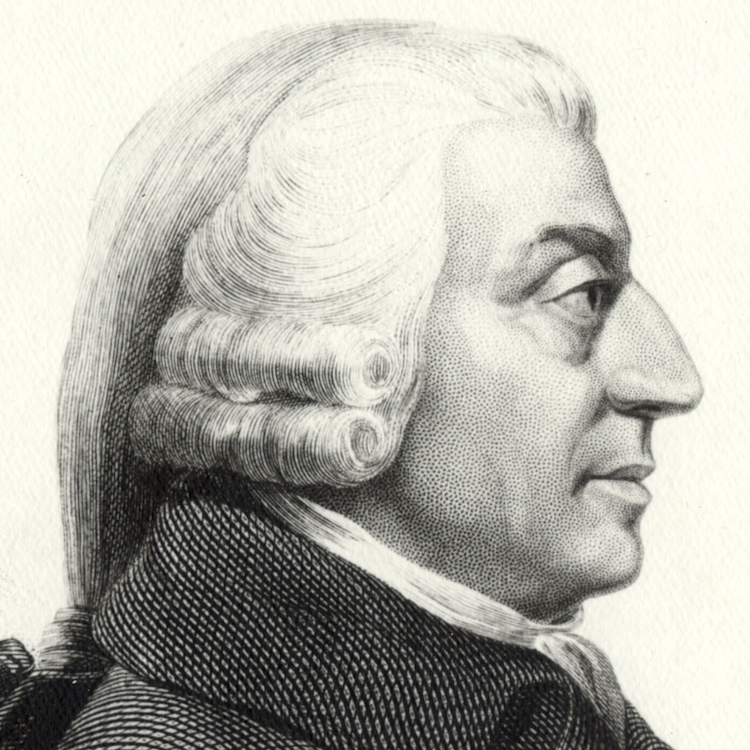

To avoid destroying everything good as well as bad, we need to return to the principles Adam Smith established in his Theory of Moral Sentiments: to practice sympathy, to regulate our own behavior, and to insist on justice as the pillar of our society.

Understanding “the Fortunes of Others”

For Smith, “sympathy” involves trying to understand the situation of someone else. It means projecting ourselves into that individual’s place, seeing and feeling the world from that position. If our brother is on the rack, Smith says,

by the imagination we place ourselves in his situation, we conceive ourselves enduring all the same torments, we enter as it were into his body, and become in some measure the same person with him, and thence form some idea of his sensations, and even feel something which, though weaker in degree, is not altogether unlike them.

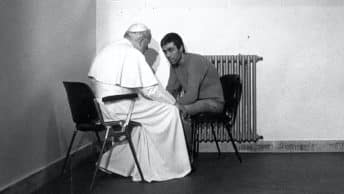

Such sympathy enables us to imagine what it might be like to be brutalized by a policeman. And such sympathy enables us to imagine being a retired policeman killed while protecting others from rioters.

Such sympathy enables us to imagine being discriminated against due to our appearance. And such sympathy enables us to imagine a shopkeeper whose life’s work is literally smashed to pieces due to her success.

For Smith, sympathy does not mean we agree with everything the other person does: it means that we try to understand so that we can judge impartially and move forward.

Flattening the “Sharpness” of Our Tone

The next step is to regulate our own behavior. An individual can only establish sympathy, Smith advises, by lowering his passions “to that pitch, in which the spectators are capable of going along with him.” He must “flatten” his tone.

Pause a moment. Are you posting on social media about your desire to have political opponents fired or evicted from their homes? Are you sending emails that emphasize the sufferings of one group but ignore the devastation of another? Are you defacing someone’s property? Are you ridiculing those who differ from you as stupid?

By stepping outside ourselves to judge our behavior, we evoke Smith’s “impartial spectator” process. We set aside our bias so that we can judge the right thing to do. We lay down our matches and start laying down a stronger foundation for our country.

Preserving “the Main Pillar” of Society

That process includes beneficence, or kindness. Smith describes it as “the ornament which embellishes” society. But the critical component is justice, which Smith calls

the main pillar that upholds the whole edifice. If it is removed, the great, the immense fabric of human society . . . must in a moment crumble into atoms.

Justice is necessary, because “the violation of justice is injury: it does real and positive hurt to some particular persons, from motives which are naturally disapproved of.” And “the most sacred laws of justice” concern three things: one’s life, one’s property, and the promises or contracts made to one personally.

Today we need justice for all those who have been killed, whether from the brutality of police officers or the brutality of rioters. We need justice for all those who have lost their property due to the greed and mischief of looters. And we need justice for all those whose rights have been violated by government representatives and regulations of all kinds.

Practicing sympathy, self-regulation, and justice requires action. As the Talking Heads say, “I don’t know what you expect staring into the TV set.” But the action must be to rebuild, to restore: not to stoke the flames, but to embrace the virtues that can restore our nation’s house.

Caroline Breashears

Caroline Breashears, is a professor at St. Lawrence who received her Ph.D. from the University of Virginia, specializes in eighteenth-century British literature. Recent publications include Eighteenth-Century Women’s Writing and the “Scandalous Memoir” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017) and articles in Aphra Behn Online and the International Journal of Pluralistic and Economics Education. She was recently an Adam Smith Scholar at Liberty Fund, and her current research focuses on Adam Smith and literature. She teaches courses on fairy tales, eighteenth-century British Literature, and Jane Austen.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.