Years ago, I was reminded of the old Broadway play Funny Girl, starring Barbra Streisand. I vividly remember taking a lady friend during Christmas week in 1965 to see what proved to be her last performance. I was most touched by Streisand’s beautiful rendition of the song People. It was a powerful ballad that expressed the deep human need that we have for other people. In retrospect, I guess the lyrics expressed comedian and heroine, Fanny Bryce’s sad lament on how she envied those who really needed people and in turn, were needed by them. To her they were the luckiest people in the world. Even today I tend to well up every time I hear that song.

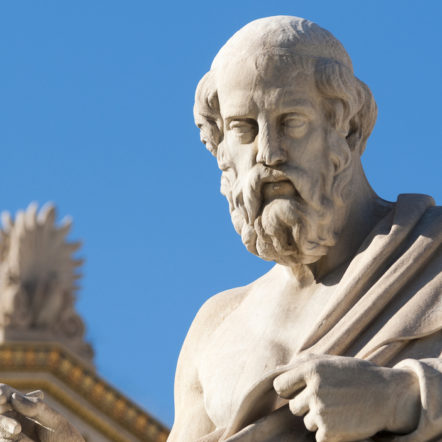

This inspired me to revisit a fascinating article in the New York Times several years ago ago. Boston College Professor, Richard Kearney wrote the article, based on a class discussion he had with his students in a class on Eros, entitled From Plato to Today.

Some of his students were bemoaning the fact that most of the romance and they were having had been too impersonalized by the Internet and the social media. They missed the real connection that virtual or casual hook-up sex can never provide.

Others admitted they enjoyed the relative anonymity of the hook up, whose consummation required no preliminary close-quarters courtship rites or flirtation ceremonies, no culinary seduction, no caress, nothing — apart from the eventual blind rut, as James Joyce had succinctly put it. They did, however, realize the tragic irony of this kind of physical connecting: that what is often thought of, as a ‘materialist’ culture was arguably the most ‘immaterialist’ culture imaginable — vicarious, by proxy, and often voyeuristic. The professor then took this mundane and earthy discussion to a much higher plane, as he outlined the philosophical and moral dichotomy between Plato and Aristotle that has plagued Western relationships for 2000 years.

Today’s cyber world of virtual dating reminded him of an updated version of Plato’s Gyges, who could see everything at a distance but was touched by nothing! Professor Kearney questioned whether we were entering an age of excarnation where we obsess about the body in increasingly disembodied ways. As Kearney states if incarnation is the image become flesh, excarnation is flesh become image. It is not surprising then, that Aristotle would see things in a completely different light. In what is perhaps the first great works of human psychology, De Anima, Aristotle pronounced the human touch the most universal of the senses.

To this Greek polymath, touch was the most intelligent sense because it is the most sensitive. When we touch someone or something we are exposed to what we touch. We are responsive to others because we are constantly in touch with another person. Aristotle was challenging the dominant prejudice of his time, one he himself had embraced in earlier works. The Platonic doctrine of the Academy held that sight was the highest sense, because it is the most distant and mediated. Plato was entirely theoretical, holding things at bay, mastering meaning from above.

Aristotle did not win this battle of ideas. Plato’s thinking prevailed for over 2000 year and the Western universe became a system governed by the soul’s eye. Sight came to dominate the hierarchy of the senses and was quickly deemed the appropriate ally of theoretical ideas. The eye continues to rule in what Roland Barthes once called our civilization of the image. Platonic thinking has culminated in our contemporary culture of digital simulation and spectacle. In effect, our world is no longer our oyster but our impersonal screen to reality.

Western philosophy thus sprang from a dualism between the intellectual senses, crowned by sight and the lower animal senses, stigmatized by touch. Western theology — though heralding the Christian message of Incarnation (word made flesh) — all too often confirmed the injurious dichotomy with its anti-carnal doctrines, prompting Nietzsche’s verdict that Christianity was Platonism for the people that gave Eros poison to drink.

For all the fascination and obsession with bodies in our society, our current technology is arguably accelerating our carnal alienation. While offering us enormous freedoms of fantasy and encounter, digital Eros may also be removing us further from the flesh. Pornography, for example, is now a global industry worth tens of billions of dollars. Seen by some as a progressive sign of post-60s sexual liberation, pornography is, paradoxically, a twin of Puritanism. Both display an alienation from flesh — one replacing it with the virtuous, the other with the virtual. Each is out of touch with the body.

Society needs to close the distance, so that Eros is more about proximity than proxy so that the soul becomes rejoined with flesh where it belongs. Such a move, I submit, would radically alter our sense of sex in our digital civilization. It would enhance the role of empathy, vulnerability and sensitivity in the art of carnal love and ideally in all of human relations because to love or be loved truly is to be able to say, I have been touched.

This movement toward privatization and virtuality is explored in Spike Jonze’s 2013 movie Her where a man falls in love with his operating system, which named itself Samantha. He can think of nothing else and becomes insanely jealous when he discovers that his virtual lover is also flirting with thousands of other subscribers. Eventually, Samantha feels so sorry for him that she decides to supplement her digital persona with a real body by sending it as a surrogate lover. But her plan fails miserably. While the man touches the embodied lover, he hears the virtual signals of Samantha in his ears and cannot bridge the gap. The split between digital absence and carnal presence is unbearable. Something is missing: love in the flesh.

Shakespeare knew this only too well. Full humanity requires the ability to sense and be sensed in turn. As the Bard wrote: the power to feel what wretches feel. Or as one might also add, what artists, cooks, musicians and lovers feel. It is becoming imperative that humans rediscover their need to find our way in a tactile world again. We need to return from head-to-foot, from brain to fingertip, from iCloud to earth.

It has become clear to me that Plato’s idealist thinking is largely responsible for the historical notion active in St. Augustine’s Confessions for the emphasis on the inferiority of the human body and its infection of Western culture ever since. Its presence has been noted in Gnosticism, Jansenism, Puritanism and the Victorian attitudes that still have born poisonous fruit into the 21st century. To counter this false perception, the Church should emphasize that Heaven is not for just our souls, but also for our resurrected bodies on the last day. This is necessary because they have been the fleshy instruments of all the good and evil we humans have ever done on earth. Perhaps in teaching St. John Paul II’s Theology of the Body, they should place a greater emphasis on the importance of touch and Eros as a unifying force in its explanation of married love. I think this is where Plato has done his greatest harm.

It has only been in my latter years that I have understood and really felt the true incarnational value of my body as fused with my soul through Massage Therapy. Over the last 13 years, my therapist has reinforced my awareness of the integral union of my mortal body with my immortal soul. As I wrote in The Hands, my unpublished short story, in her hands his body and soul had quickly become whole again, dispelling any Platonic notion about separation…they were reunited in a paroxysm of emotion that transcended life and even death. This thoughts drips beautifully with the fleshy touch of Aristotle.