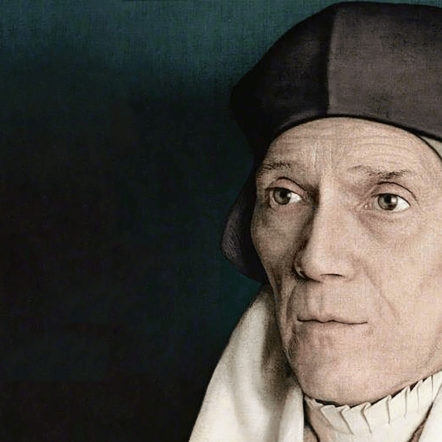

June 22: We know less than we ought about the saint whose martyring for his faith occurred on this day in 1535. That would be, not the universally recognized St. Thomas More, but instead his less familiar co-saint of the day, St. John Fisher. And why is that? Fisher’s lesser renown, that is? Is it because More, the man for all seasons who went some fourteen days later than did Fisher to the executioner’s busy block of that Henry VIII era, is a hard man to share a stage with? Yes, for sure, to some extent that’s the reason—so redoubtable a figure in our Catholic consciousness is More, with or without the Robert Bolt play and movie of the 1960s that gave him his resonant moniker. But is it the whole of the reason? And, darn it, who was St. John Fisher anyway?

Those are the pair of questions I’ve been trying to answer in the last few days as the Fisher/More feast day approached. Here’s what I found out:

(i) Born in 1469 in the town of Beverly, Yorkshire, England, to a prosperous mercer (dealer in textiles) and his wife, Fisher would share his birth year forever after with the Italian Niccolò Machiavelli, author of The Prince, who, too, like Fisher, would have occasion to think hard in his lifetime about questions of plain-spokenness and non-plain-spokenness in the public domain. The two would come to decidedly different conclusions, of course, and yet still they were born in the same year.

(ii) He was educated at Cambridge University–then a not so shining institution, though, given his shining intellectual performance in the years that followed, there is little evidence that its program dulled Fisher’s mind.

(iii) He was ordained a priest in the year before Columbus’s sailing, 1491. So, yes, the times were a-changing.

(iv) From 1491 through 1501, he stayed on at Cambridge studying theology, preaching locally, and, growing up professionally as a University proctor. His campus theme in those years—not yet those of Luther and of the Protestant Reformation per se–was that priests, for the sake of their preaching, should get more training in theology and scripture.

(v) Sometime in the mid-1490’s, he began to serve as confessor and counsellor to the “lady-mother of the King,” Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII and grandmother to Henry VIII. The two collaborated in the founding of St. John’s College, Cambridge. Also, and importantly as I see it, this appointment was Fisher’s entryway into the souls of his country’s first family, so to speak.

(vi) In 1501, he became Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University. Some three years later he became its Chancellor, and, by all accounts, he did the job well.

(vii) One of his more telling moves as Chancellor was to hire, for a time at least, the Dutch theologian and Greek scholar Desiderius Erasmus. What was telling about this was that Erasmus was at the forefront of new, as opposed to old, ways of seeing Scripture and the material world at large. This tells us that Fisher was ahead of, as opposed to behind, his times. (As for Erasmus’s opinion of Fisher, he said of him, “He is the one man at this time who is incomparable for uprightness of life, for learning, and for greatness of soul.”)

(viii) About the time he was assuming the Chancellorship of Cambridge, he was also appointed Bishop of Rochester, then England’s poorest diocese. This job too he was good at—caring for the souls of his flock and leading his priests in a humble, methodical fashion, that is.

(ix) In particular, as bishop he went out of his way to care for the souls of the poor and dying among his flock. His biographers tell stories of his crawling into dismal, airless huts to be with the dying.

(x) Also, as bishop he distinguished himself from his brother prelates by the simplicity of his lifestyle. Indeed, in this regard a Fisher anecdote is worth recalling: A newly, irregularly appointed Cardinal Wolsey had just called to order his first synod of English bishops when, unscheduled, up stood the lean Bishop of Rochester to speak. His theme? “The ambition and incontinency of the clergy [and too] their vanity in wearing of costly apparel.” The speech was said to have “touched [the Cardinal] to the very quick,” for, yes, he was a fat man, well threaded, and ambitious.

(xi) Did Fisher, however, as bishop ever overstep his mark in those of his activities that might be seen as foreshadowing his own troubles with the King? Those would be the heresy cases that came before his episcopal chair. Yes, think about it. The short answer for those who unfailingly admire the man would be no, and their principal argument would be that no unruly soul ever brought before Fisher for unorthodox speech went away unpersuaded to abjure and, thus, not a single hair was ever lost by way of a Fisher heresy ruling in his own diocese.

And that’s the position I’ll largely take here, even though, yes, to get to it I and they who made it before me have to work our way through all that is untidy in, for example, the case of the man brought before Fisher in 1507 for having said aloud that offerings and offering days were only ordained by priests and curates for their own “covetous avayles” [advantages], and, by so speaking, had caused a female neighbor to withhold her offering. Yes, those were the charges brought against the man.

But, hey, from all we know today of the Church in Fisher’s time and of its venal clergy, and from all that Fisher even better knew, the guy might have had a point, no? And, yet still, Fisher got him to abjure and imposed on him, not only the usual penance of going in procession and not leaving the diocese for four years, but also too the additional requirement that he come back annually for the whole of those four years to meet with him, the bishop. Yes, what to make of this ruling? This, perhaps: That the guy got to air his grievances (in front of the Bishop, no less), that both faith and discipline by Fisher’s ruling were affirmed, and that, too, who knows what went down between the Bishop and the recalcitrant member of his flock in their subsequent four meetings.

(i) On the other hand, re Fisher and the heretics: No one–save, perhaps, Thomas More (see below)– wrote more apocalyptically of the dangers posed by heretics to Christendom than did Fisher. They were “murderers of souls,” and so on. Was this language injudicious? A heaping of kindling beneath the feet of alleged heretics outside his diocese? Fisher’s defenders say in this regard historical perspective matters: that Fisher’s language was of a piece with the homiletic rhetoric of the day and, too, with late-medieval, early-modern theology then regnant. Lastly, to his credit, it was the same brand of spiritual-warfare theology that made necessary Fisher’s choosing death rather than reneging on his faith at the end of his life.

(ii) In 1507 and then two years later, Fisher preached at the funerals of Henry VII and Lady Margaret—father and grandmother of Henry VIII. He was, in other words, as I’ve already mentioned, the Plantagenet-Tudor household’s go-to priest and unofficial spiritual director. Very likely, Henry VIII cared what he thought.

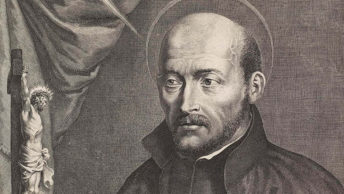

(iii) Fisher was a formidable apologist and theologian. Writing under his own name, he put out some of the key English-language refutations of Martin Luther’s complaints. Also, beyond that, it is said too that he ghostwrote for others, including, a younger Henry VIII, whose pamphlet Assertio septem sacramentorum adversus Martinum Lutherum (“Declaration of the Seven Sacraments Against Martin Luther”) won him (Henry) the title Defender of the Faith.

(iv) Next, to return to his relations with the royal family: Did that intimacy influence Fisher’s preaching? In other words, in his sermons did he play nice with the powerful who were his acquaintances? No, he did the opposite. That’s my impression as I read a summary of that 1520 sermon of his in which he advised his listeners that life is short, that this world’s splendors count for nothing on one’s Judgment Day, and that the ashes of Edward, Richard, and the “King that is now dead” testify to that truth. Yes, for sure, he had backed off from naming Henry VII in the same way that he had named the kings of rival-to-Tudor households. However, the reigning Henry’s father had been pointed to no less than the others, and what was the point of the whole sermon if not to admonish the current King that pomp, circumstance and power brought with them their spiritually perilous delusions? Beware, was saying the Bishop to the King, your soul, not just your kingdom, is at stake on a daily basis. Was Henry in the pews that day. No, my source for this sermon does not indicate that he was. And, yet still, trust me; he heard the sermon.

(v) The quarrel between Bishop and King that would ultimately result in Fisher’s martyring in June of 1535 would begin in earnest eight long years before, in May of 1527, when, as a matter of supposed conscience, Henry started seeking an end to his now 18-year-long marriage to Catherine of Aragon. That appeal went first to Wolsey, but soon enough it got to Fisher, whose credibility among the people was far greater than the Cardinal’s. He took some time to consider the matter, eventually decided against it, and, according to one early biographer, delivered that sentiment personally to the King himself.

(vi) And now the dye was cast. It was the King’s will vs. God’s will, and the most notable churchman holding out for the latter was the Bishop of Rochester. It was only a matter of time until the Bishop’s neck was on the chopping block, for, as everyone knew in those days, ira principis mors est (“the king’s anger is death”).

(vii) You know the rest of the eight-year story, or at least its third-to-last scene: Locked up in the Tower for some fourteen months, starved and lice-plagued, Fisher is visited by a someone representing himself as an emissary from Henry himself, and that someone is asking the Bishop on the King’s behalf what the prelate actually thinks in regard to the now Head of Church issue in question. The King wanted to know because, yes, he too had a soul and he realized it was at stake.

(viii) Wow! What a diabolically devised trap! Up until that moment, Fisher had been keeping alive by doing like Paul in Rome, that is, by insisting on his rights as a citizen, inclusive of the right to say no more nor less than he wished on the question of the King’s Supremacy. But now a soul at risk was seeking his counsel. It was a stratagem so transparently false that only a shepherd of souls of the cut of Fisher’s cloth could allow himself to be ensnared by it. He told the someone what he thought, and some six weeks later when he was brought to trial for treason he did not deny having said what he had said.

(ix) Lastly, some five weeks after his trial’s conclusion, on June 22nd, 1535, Bishop John Fisher was beheaded. His sentencing had originally called for his hanging, drawing and quartering. However, for reasons mysterious, the King intervened. He said that beheading would be enough.

So that’s what I’ve learned about Fisher in the last few days. As for his story’s lesser notoriety than More’s, no, I don’t find anything in it that would explain that reality. Certainly not Fisher’s strong opinions on heresy, for, as I’ve learned, More’s were no less strong. Then, too, those extra fourteen days that More waited in the Tower knowing that he was next—they, I thought for a time, might distinguish him from Fisher. However, that could hardly be the case either, given that Fisher’s execution was preceded by those of several other Papacy loyalists (https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/saint/english-carthusian-martyrs-227). If, for reasons of geography, Fisher hadn’t actually heard the racket occasioned by their executions (as More no doubt heard the commotion occasioned by Fisher’s), he certainly knew of the goings on at Tyburn and was made to think hard about his own choices in the days that followed. And, lastly, there was Fisher’s shrewd legalism in insisting for many weeks that he had a right to keep his thoughts to himself. Did that in any way distinguish his witnessing to the Truth from More’s? No, because More—like, again, Paul in Rome—availed himself of his citizen’s rights until tricked into doing otherwise.

So, no, I don’t know why everyone knows the More story but few know Fisher’s. Nor, to tell you the truth, do I much care because, darn it, More plays the lead-saint role well. Or maybe I don’t much care because as a result of all my research I know to be true about More and Fisher what my Irish mom used to say about those of her sons that were twins (Jim and me): there’s not much in the difference. Yes, between More and Fisher there’s not much in the difference.