Recently I had the grace of following the module Early Jewish and Christian archeology and art in the course, The Beginnings of Christianity within First Century Judaism, organized by the Pastoral Formation Programme of our Archdiocese of Malta.

Art and archeology are certainly the result of countless hidden stories and life experiences which an endless number of people go through in their troubled lives. In fact, their life experiences leave behind a living heritage and an influence for future generations to follow.

A case in point is surely the book by Rabbi Harold Kushner, When Bad Things Happen to Good People. The title assures us of one thing: bad things unquestionably occur in life, even to good people. Moreover, the first word of this intriguing title says it all: the question is not why but when bad things happen to good people. In few words, bad things can happen any time in any space and at any time. In front of such a title, I just could not sit back and say nothing at all. This title not only made me read the book throughout but also prompted me to offer my pastoral response to it.

In my work as a hospital chaplain with cancer patients at Sir Anthony Mamo Oncology Centre at Birkirkara, in the island state of Malta, I always ask the question as patients and their relatives do ask continually: Why do bad things occur to good people? For instance, he was so charitable, respectful, industrious within his family, he had a caring wife and two beautiful children to look after, why did he have to die so early? Is it fair that a family is devastated due to a loss of an innocent child? What did that child do to merit such a death? And, in this vein, allow me also to ask the question on my life story too, as a hematology patient: Why did God allow me to have a myeloproliferative disorder? How can I serve him with this condition in my bone marrow?

Harold Kushner, the Jewish Rabbi, a man of great faith, has been swimming into these rough waters himself. As a matter of fact, this insightful book is his human and spiritual reaction to the premature death of his son Aaron. When confronted with this personal tragedy, Kushner had the courage to put pen to paper by sharing all his inner reflections on what he was experiencing as a bereaving parent. He did not simply do this because he felt angry about this very unfair situation but also he felt to reach out and be of support to those people who they too have been badly hurt by life. He was sensitive to the call of journeying with them in their quest for a faith that could help them sail through life’s troubles.

When faced by such a tragedy, especially when the patients are children, I too start thinking and reflecting harder on this heartbreaking situation. Sometimes patients and even parents of children with cancer, tell me in their grief: If God is a healer than why is He not healing me, my son or daughter? What wrong did they do to merit such a punishment? If God is just why did He not give this punishment on me and spare my daughter and son from this terrible tragedy?

To begin with, Harold Kushner teaches me a big lesson when he writes: “The God I believe in doesn’t send us the problem.” (p.127). Hence, God does not send cancers and all kinds of sicknesses on his children whether adults, young people or children. That is a sigh of relief! However, if God didn’t cause the emergence of cancers, can’t He do a little bit more to fix the situations, particularly when good people are involved?

Before answering this important question, Harold Kushner taught me another big lesson: nice people are not at all spared from suffering. Indeed, for Kushner, some suffering is caused by the work of natural law which is blind. We know that God does not interfere to save good people from earthquakes or disease. And He does not punish the bad either. Seen from this perspective, Kushner helped me realize that since some suffering is circumstantial, because one happens to be in the wrong place and at the wrong time, is there a point of looking for a reason to explain that tragic and bad situation?

And if God seems to be, at least in certain circumstances, like the ones I frequently come across when children die at our hospital, in spite and despite the prayers we pray day and night for their healing, what’s the point of praying to this seemingly non-omnipotent God? Upon reflecting on what Kushner wrote, coupled with my own personal experiences, I have come to the conclusion that praying to God makes us aware of two important things: namely that the prayers of others can make us aware that we are not, in truth, facing our problems alone. And secondly, thanks to their prayers, God can give us the strength of character that we need to handle our misfortunes, provided that we are willing to accept that they have actually occurred to us.

One thing which really amazes is the fact that certain people, even if they underwent experiences of tremendous suffering, are there to help. A case in point is the fascinating phenomenon that a good number of parents who lose their children to cancer often become actively involved in the Puttinu Cares Foundation. The foundation’s aim is: “(1) To advocate on behalf of affected children and their families by representing their needs; (2) To campaign for the provision of a coordinated network of care and support; (3) To promote models of good care and practice; (4) To support families with a national information service; (5) To enhance the knowledge and skills of professional careers by providing specialist literature and education opportunities; (6) To assist affected children by improving the environment in which they are treated; (7) To raise funds through sponsorships, donations and fundraising activities or through any other means as the Management Committee may determine; and (8) In general to do all that is conducive to the attainment of the above aims” (PUTTINU CARES HOME AWAY FROM HOME, Our Aim, https://puttinucares.org/about-us/our-aim/

Such a phenomenon of parents of children suffering from cancer who decide to help in the running of Puttinu Cares Foundation justifies what Harold Kushner himself wrote about God: “The God I believe in doesn’t send us the problem; He gives us the strength to cope with the problem” (p.127). Is this not an excellent way of stopping the hurt within ourselves and becoming open to God’s help? Is this not a productive manner of responding to our anger for the situation by helping people who are swimming in the same waters as us?

Reading between the lines of Kushner’s argument, God’s Spirit led me to the conclusion that even if suffering can create isolation, God still gives us the strength to use suffering as a catalyst for communion of love and support. It is true that there are situations where, the more we try to understand the situation, the more we do not understand it. However, if we just accept the fact that our world is not perfect, to accept the way God acted in that situation, to reach others who need our support and keep going on no matter what, this will surely overturn our response from a passive and destructive one into an active and an abundantly fruitful one.

Thus, Kushner writes:

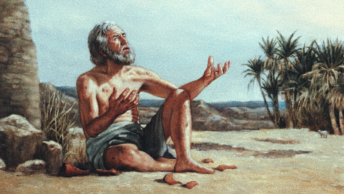

“Is there an answer to the question of why bad things happen to good people? That depends on what we mean by ‘answer’. If we mean ‘Is there an explanation which will make sense of it all?’… then there probably is no satisfying answer. We can offer learned explanations, but in the end, when we have covered all the squares on the game board and are feeling very proud of our cleverness, the pain and the anguish and the sense of unfairness will still be there. But the word ‘answer’ can also mean ‘response’ as well as ‘explanation,’ and in that sense, there may well be a satisfying answer to the tragedies in our lives. The response would be Job’s response in MacLeish’s version of the biblical story—to forgive the world for not being perfect, to forgive God for not making a better world, to reach out to the people around us, and to go on living despite it all” (p.147).

Even if we do not have a full control of the bad situation that strikes us, it is solely with us that resides the choice if we open ourselves to the help that is being given to us or simply reject it. God certainly keeps inviting us to do our part so that we might continue receiving the utmost of that help. Kushner writes:

“The conventional explanation, that God sends us the burden because He knows that we are strong enough to handle it, has it all wrong. Fate, not God, sends us the problem. When we try to deal with it, we find out that we are not strong. We are weak; we get tired, we get angry, overwhelmed. We begin to wonder how we will ever make it through all the years. But when we reach the limits of our own strength and courage, something unexpected happens. We find reinforcement coming from a source outside ourselves. And in the knowledge that we are not alone, that God is on our side, we manage to go on” (p.129).

Thus, Kushner’s book liberated me and my patients, families and staff members I try to serve, from faulty reasons explaining why one might not get what s/he is praying for, such as I don’t deserve it, I didn’t pray hard enough, God knows better than I what is best for me, someone worthy was praying for the opposite result, God doesn’t hear prayers and there is no God.

Instead, let us pray for connecting ourselves with other people. Kushner writes:

“One goes to a religious service, one recites the traditional prayers, not in order to find God (there are plenty of other places where He can be found), but to find a congregation, to find people with whom you can share that which means the most to you. From that point of view, just being able to pray helps, whether your prayer changes the world outside you or not” (pp 121-122).

Then we can also ask God to strengthen our character so that we can deal with the adversity that we are facing.

“People who pray for miracles usually don’t get miracles. … But people who pray for courage, for strength to bear the unbearable, for the grace to remember what they have left instead of what they have lost, very often find their prayers answered” (p.125).

Is my pastoral presence facilitating the fact that God, in front of “the [neutral] facts of life and death” (p.138), can still provide us with that much-needed strength to face reality? If it does, then I am walking in the right direction. If not let me read Rabbi Kushner’s book for my daily pastoral examination of conscience, let it speak to me and then go out and let suffering people keep teaching me how I should listen to them through my God-given closeness, tenderness and compassion.

Be pleased, O God, to deliver me! O LORD, make haste to help me! (Ps 70:1).