This essay continues the discussion begun in “Theological Confusion” and published in this journal December 13, 2012

This essay continues the discussion begun in “Theological Confusion” and published in this journal December 13, 2012

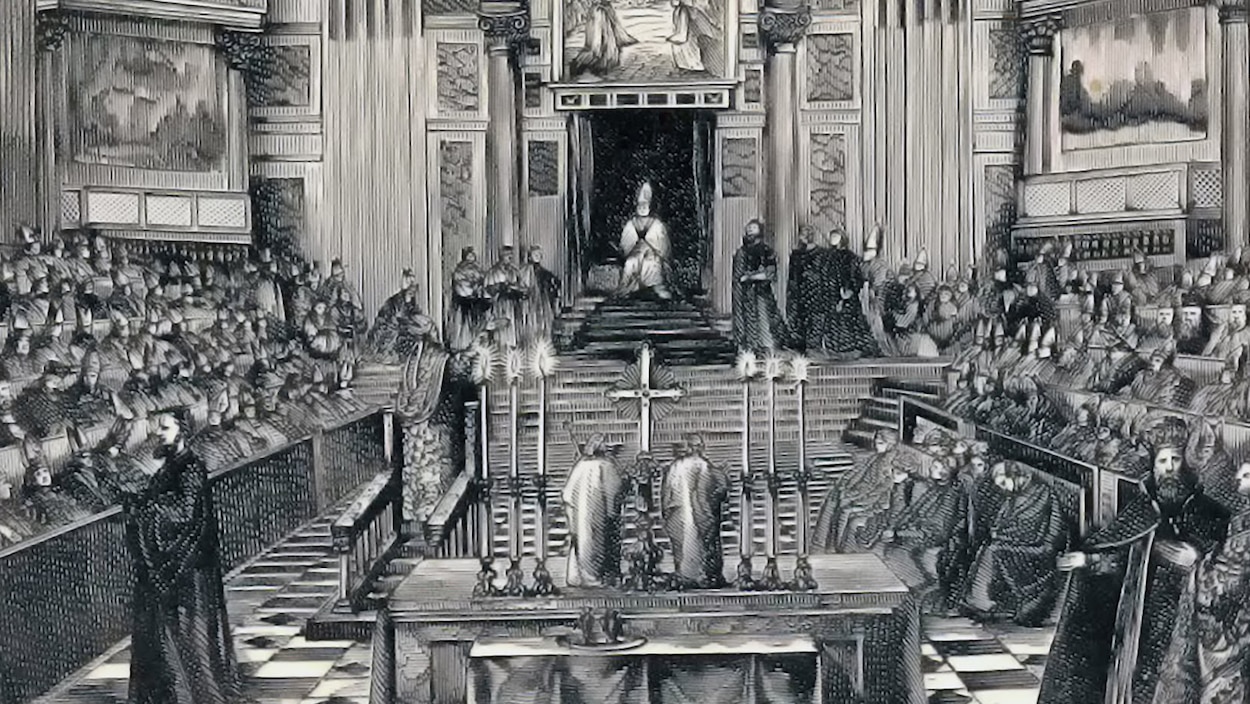

In 1870 Vatican One proclaimed papal infallibility an official dogma of the Catholic Church. Almost a century later, humanistic psychology proclaimed, via Carl Rogers, that everyone is his or her own authority and creates his or her own truth and reality. In addition, the new psychology declared that emotions are more trustworthy than the intellect and should therefore be expressed without restraint.

The two proclamations have more in common than is apparent. Both assert a form of infallibility—that is, freedom from error. In the case of the Church, infallibility is considered a gift of the Holy Spirit received under certain circumstances by the Pope alone or the Pope and his fellow bishops. (The term Magisterium is used to denote the Pope together with the bishops.)

In the case of humanistic psychology, infallibility is considered inherent in the human condition and is enjoyed by everyone all the time. Whatever anyone believes is true or moral is by that very fact true or moral; hence, no thought is ever mistaken and no deed is ever immoral.

It is interesting to note that papal infallibility is quite modest in comparison to humanistic psychology’s infallibility—one person or a small number versus all people, and sometimes versus always and everywhere. Yet the idea of papal infallibility has met considerable skepticism, while humanistic psychology’s claim has become a mainstream idea. Ironies abound.

Although Catholics are required to accept the Church’s teaching on infallibility, like everyone else they are free to reject humanistic psychology’s teaching. And reject it they should, despite its continuing fashionableness and appeal to diversity, because even a moderately bright seventh grader could easily refute it.

Entire societies and religions, including Catholicism, have been convinced that the sun revolves around the earth, only to discover that they were mistaken. Almost half the earth’s population believed that bubonic plague was caused by sin or bad air and could cured by penance or washing with vinegar and rose water, applying tree resin and human excrement to the sores, or drinking one’s own urine. (Pope Clement VI looked to astrology for a more definitive answer.) And many individuals and groups continued to argue that the earth is flat long after that notion was proved false. Even now, when photographs from outer space provide indisputable visual proof that the earth is spherical, there is still a Flat Earth Society, with its own website, a bookstore, and a standing appeal for new members.

As for the companion notion that there is no such thing as immorality, history offers innumerable examples of behavior that qualifies for that classification—including slavery, persecution, rape, torture, child abuse, and murder. Anyone wanting current evidence that people are not always wonderful, or wise, can find it in virtually any newscast.

Nevertheless, Humanistic Psychology’s strange version of infallibility has persisted for decades and produced a number of unfortunate consequences in many people:

- Inordinate confidence about the breadth and depth of their knowledge, often despite obvious evidence to the contrary. (Interestingly, Socrates, one of the wisest men who ever lived, took the humble view that “the only thing I know is that I know nothing,” which interestingly provided the motivation to become wise.)

- Diminished interest in learning from others in school, at home, or in the workplace. (There is no point in people seeking enlightenment from others if they believe they already know everything worth knowing.)

- Increased disdain for rules and standards that originate outside themselves, including those set forth by parents, teachers, religious leaders, government officials, and even God.

- Infatuation with their own opinions and resentment of people who do not share them or, worse, who challenge them.

- A dramatic shift in the general view of the self from something to be controlled to something to be indulged, as evidenced in the preference for words like self-esteem, self-actualization, self-gratification, and self-fulfillment over words like self-abnegation, self-mastery, and self-sacrifice.

- An increase in behavior, notably sexual behavior, traditionally proscribed by religion and the general culture.

Religion was not immune to the influence of Humanistic Psychology. Spiritual counselors were introduced to it in graduate schools and in conferences with their secular peers. Religious orders took part in Carl Rogers’ “Encounter” groups. Such encounters effectively eliminated the Immaculate Heart of Mary (IHM) order of nuns and had a significant impact on a number of other orders, including the Jesuits, as Malachi Martin and Joseph Becker have documented. The influence of humanistic psychology is still manifest in the demands of religious “progressives” that Rome affirm gay marriage, abortion, and women priests.

The fundamental error of humanistic psychology was to embrace a view of human infallibility that did not comport with the reality of human nature, specifically human imperfection. As a result, the new psychology did not anticipate the lamentable consequences its perspective produced. (Carl Rogers himself eventually admitted as much, though the admission came too late to have any effect.)

The fact that humanistic psychology’s extravagant claim of infallibility is mistaken does not necessarily mean that the Church’s more modest claim is flawed. Nevertheless, the legacy of humanistic psychology’s doctrine of human infallibility may contain valuable lessons for the Church.

Before considering those lessons, let’s set the historical context. The Church has traditionally believed that human nature is imperfect—that is compromised by Original Sin. The chief characteristics of that imperfection are that the human intellect is clouded and the human will is weakened. In practical terms, that means we can attain truth only by seeking it and avoiding the errors to which our imperfection makes us prone. “Actual grace” aids all human beings in that process; the sanctifying grace of Baptism provides special aid to those who receive that sacrament.

The Church’s dogma of infallibility, however, implies that the Magisterium enjoy not just the special aid given to all those anointed in Baptism, but something arguably more powerful—a dispensation from the imperfections of human nature, at least when they are speaking infallibly. According to the current edition of the Catechism (# 892), when the bishops propound ordinary teaching about faith and morals in communion with the Pope, they receive “divine assistance.”

What we know of the errors of humanistic psychology’s doctrine of infallibility understandably makes thoughtful people, if not suspicious, then at least curious about this supposed dispensation from the imperfections of human nature. The following questions concern how Catholics should understand the dogma of infallibility:

- Does the Holy Spirit provide the Magisterium with both the thoughts to be expressed and the manner of their expression, or does it instead simply encourage or prompt the bishops to undertake a search for discernment of the truth? If the former, then the Magisterium surely cannot err because God cannot err. If the latter, then infallibility can occur only if the Magisterium responds to the Holy Spirit’s prompting by mastering their egos, overcoming pride and preconception, and avoiding the fallacies to which the rest of us are vulnerable, such as oversimplification, overgeneralization, and hasty conclusion.

- Does the Holy Spirit’s guidance make it unnecessary for the Magisterium to study the findings of research in fields related to matters of faith and morals? If so, they can speak and act with certainty even in areas about which they would otherwise have insufficient knowledge to make informed judgments. If not, they should thoughtfully examine competing views of an issue before offering any view on it. For example, before making pronouncements about “social justice,” they should consult the various viewpoints offered by economists and psychologists, among others. Similarly, before offering their views on legal and illegal immigration, they should seek insight from experts in law and demography. (Often as not, the pronouncements that are made offer no clear evidence that such consultation has occurred.)

- Is it possible for the Magisterium to be deceived into believing that the Holy Spirit is guiding them in situations where, in reality, ego or excessive self-esteem is doing so? If so, then prudence requires them to cultivate humility and subject their own views to the same rigorous critical analysis they apply to the views of those who disagree with them. (As I have pointed out in this journal, on at least one important issue, social justice, such rigorous critical analysis is not evident. See “American Catholics and Social Justice” in the archives.)

Catholics believe the Holy Spirit guides the Church because, as Jesus promised, “the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” There can be no reasonable doubt that some, and perhaps most, of that guidance comes through the pope and the bishops.

But Scripture informs us, as well, that all of the faithful are anointed (John 2:20, 27; 2 Corinthians 1:21). So there can be no reasonable doubt that some of the Holy Spirit’s guidance is given through those outside the Magisterium, namely priests, deacons, religious, and the laity. It follows that one of the requirements of leadership for the Magisterium is to be open to and alert for not only the guidance that comes directly to them from the Holy Spirit, but also the guidance that comes indirectly, from the people.

Exactly when should the Magisterium expect that guidance from the people to be manifest? Not when the people agree with them, for on those occasions the people show obedience (a different kind of virtue). Instead, the Magisterium should expect that guidance when the people disagree with them. And it is precisely on those occasions when the Magisterium are likely to be tempted to dismiss what they people say and even to censure them for saying it. Two obvious sources of that temptation are the pride and increased sense of importance that accompanies their elevation to the Magisterium, and the Church’s declared dogma that asserts their infallibility.

There is also a third source of temptation to reject guidance from priests, deacons, religious, and the laity—the ego-inflation generated by humanistic psychology’s doctrine of human infallibility that has influenced virtually everyone in western society, including those in the Magisterium. There is a double irony in this temptation: it derives from a school of thought that is among the most powerful foes of Christian belief in the last century; and it prevents the Holy Spirit from working through the people.

Perhaps the most important lesson the Church can draw from humanistic psychology’s half-century of success in promoting its version of infallibility is this: When people have been persuaded of their own infallibility, they are not likely to be impressed by the claim of the Magisterium’s infallibility. Nor are they likely to pay much attention to pronouncements made under that banner.

I can’t help wondering whether a better way to present the Gospel to people so long deceived might be an unexpected demonstration of humility.

Copyright © 2012 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved