Early Years – Vatican Nuncio to Germany 1917-1929

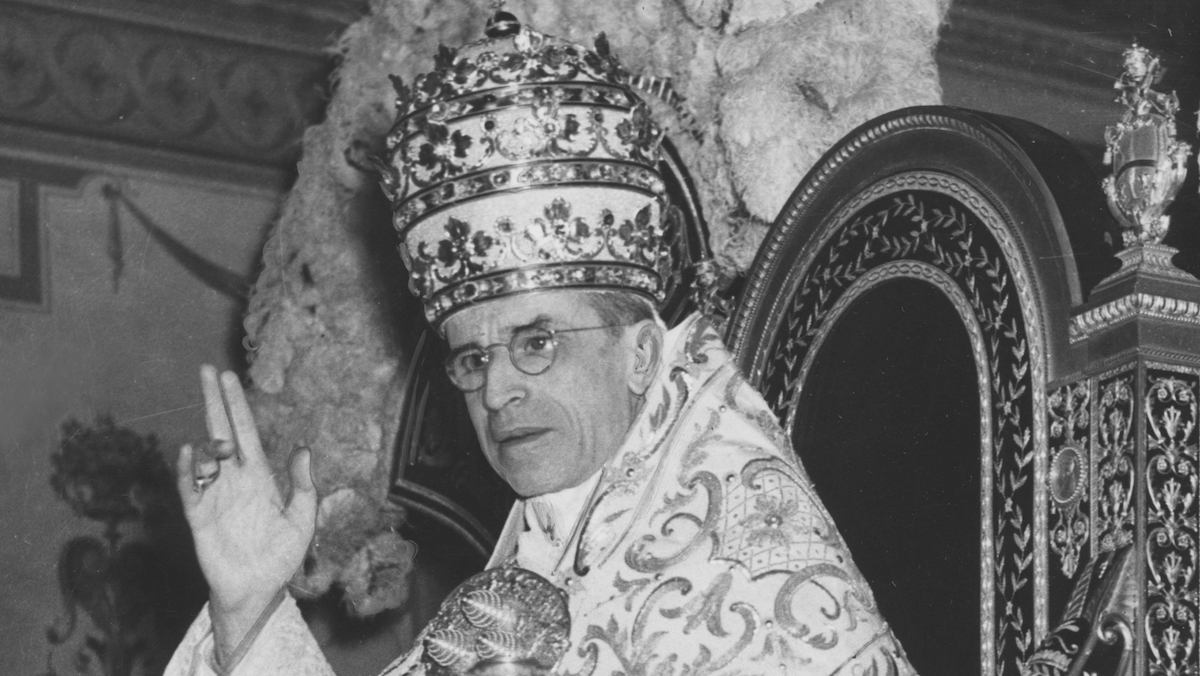

Eugenio Pacelli was born in Rome on March 2, 1876. His family had a long pedigree of service to the Vatican as members of the “Black Nobility.”[27] His great grandfather was Finance Minister under Pope Gregory XVI, his grandfather served as Under Secretary of the Interior for Pius IX, and his father was Dean of the Vatican Lawyers.[28] His brother Francesco, also a Vatican lawyer, played a principal role in the negotiation of the Lateran Accords with Mussolini’s Italy in 1929, and his cousin Ernesto Pacelli was a financial advisor to three popes and president of Banco di Roma that had extensive business dealings with both Pope Leo XIII as well as the Vatican. Needless to say, the Pacelli family had an open door inside the chambers of the Vatican upon request. After obtaining degrees in law and theology, Pacelli went on with his studies to complete his doctorate in Canon Law (his doctoral dissertation was on Concordats). Pacelli was ordained a priest in April 1899, became nuncio to Bavaria in April 1917, and then nuncio to all Germany in June 1920. After serving nearly thirteen years in Munich and Berlin, he returned to Rome and was named a Cardinal in December 1929 by Pius XI. Pacelli then replaced Pietro Gasparri as Cardinal Secretary of State in February 1930 and ascended to the papacy in March 1939.

It was his family history, no doubt, that was instrumental in Cardinal Pietro Gasparri selecting Father Pacelli at the dawn of the twentieth century to be his protégé inside the prestigious office of Vatican Secretary of State. At that time, Rafael Merry del Val was serving as Cardinal Secretary. Beginning in 1904, Gasparri and Pacelli worked tirelessly on writing the Code of Canon Law, one of the most important legal documents in the Catholic Church that set down ecclesiastical rules and re-defined the role of the Pope in relation to the Church. John Cornwell explains the significance: “The code was to be applied universally without local discretion or favor. It described the lines of authority, and laid down rules, and penalties. It transformed the power of the papacy and thus the consciousness of what it meant to be a Pope, and a Catholic.”[29] The Code of Canon Law was published in 1917 and distributed to every Catholic Church worldwide as the fundamental reference handbook of Roman Catholicism until it was replaced in 1983.

Pacelli was multilingual and acclaimed for his assiduous work ethic and photographic memory. From 1904-1917, the young priest worked his way up the Church hierarchy tackling various assignments within the Department of Extraordinary Affairs. During these early years of his ministry, Pacelli was called upon to help devise a Catholic response to the growing crises of anticlericalism in France especially after the enactment in 1905 of the laws separating Church and State and the 1906 ruling in the Dreyfus Affair that polarized the nation.[30] Author John S. Conway sees a link between the French humanist movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to the French Revolution of 1789: “The French Revolution was the first movement in modern times to attempt to replace Catholicism, with its supernatural frame of reference, by a secular religion of humanity, which, in various forms, runs through the subsequent history of Europe.”[31] In 1905, The French wanted the church out of political affairs and the government responded by closing Catholic schools and monasteries and forcing Jesuits and other religious teachers out of the country. While on assignment in France, Pacelli conferred with bishops and provided detailed reports to Gasparri and Cardinal Secretary Del Val on how Pope Pius X should respond to the deteriorating conditions with the French government.

Anticlericalism in France was not the only issue that Pacelli tackled first hand. At the turn of the twentieth century one of the central questions confronting the Catholic Church was how it would adapt to a changing world. The industrial revolution caused cataclysmic changes in both Europe and the United States as populations migrated from farms to cities in search of educational opportunities, employment, and a bourgeois lifestyle which included all the vices that accompanied the growth of a modern city: prostitution, bawdy shows and cafes, speakeasies, sexual promiscuity, and other forms of art and entertainment that was frowned upon by the Church as “sinful.”

The dramatic influx of people to cities resulted in poor housing conditions, crime, political corruption, poverty, and rampant disease. Churches were thus called upon to provide not only spiritual solace but also charity to the needy.

The Vatican was also reeling from an increasingly secularized European society as a result of the Modernist Movement. In addition to contributing to the general decline in morality, the Vatican believed that Modernism was an affront to Christianity, raising questions about the supernatural aspects of the faith and replacing it with a more rational scientific worldview. Hubert Wolf notes that Pacelli was troubled by the loose morals he witnessed in the German Catholic laity during the post-World War I period reporting his concerns to the Vatican:

Pacelli’s depictions gave the authorities in Rome a relatively clear picture of the Catholic laity. While the Catholics in the countryside were still largely under Roman control, the workers, and particularly the Catholic upper classes, were increasingly becoming emancipated from the magisterium in terms of faith and morality. As far as Pacelli was concerned, this state of affairs resulted from the false attempt to reconcile Catholicism and modernity in all areas of life.[32]

Social Darwinism and eugenics were likewise gaining influence as philosophical markers for determining the composition of dominant races and societies that would later be the basis for Nazi assertions of Aryan supremacy. These social sciences later influenced Nazi doctors including Hitler’s personal physician, Dr. Karl Brandt, who willingly administered the “Aktion T-4” euthanasia program in 1939. [33]

During this pre-1917 period, Pacelli traveled to Belgrade, Vienna, and other European capitals meeting with nuncios and assisting in negotiations of concordats reporting daily to his superiors. In August 1914, just as the horrors of World War I were beginning to take shape, Pope Pius X died. His replacement was Pope Benedict XV who in turn elevated Pacelli’s mentor, Pietro Gasparri, to Cardinal Secretary of State.

In April 1917, Germany was mired in a costly war of attrition. The economy was reeling from the demands of the Wehrmacht entrenched in Belgium and France. Soldiers along the fronts were in constant need of munitions, food, and other provisions draining vital resources from the economy that would otherwise be used to meet public demand. Back home, the German people were suffering from food shortages, political unrest, and a mounting list of casualties. War weariness was taking a toll on the psyche of the nation. Overtures for peace seemed to be a chimera. The belligerents were in a deadlock both in the trenches and on the diplomatic front.

It was into this maelstrom of political and social upheaval that Pope Benedict XV called upon Eugenio Pacelli to serve as Vatican Nuncio in Bavaria after the death of Archbishop Giuseppe Aversa in April 1917. In his baptism of fire, Pacelli was assigned the critical task of acting as a liaison to deliver an important Vatican peace initiative to Kaiser Wilhelm and Chancellor von Bethmann-Hollweg. Charles J. Herber asserts that Pacelli was well received by the German diplomatic corps at the time of his appointment, “His courteous manner, his tact, his restraint, and especially, from the German point of view, his willingness to speak as someone other than a rabid Italian nationalist made an excellent impression on the officials with whom he had spoken.”[34] Kaiser Wilhelm II also praised the Vatican Nuncio after meeting him in 1917: “In the summer of 1917 I received at Krueznach a visit from the Papal Nuncio, Pacelli, who was accompanied by a chaplain. Pacelli is a distinguished, likable man, of high intelligence and excellent manners, the perfect pattern of an eminent prelate of the Catholic Church.”[35]

Although Pacelli worked tirelessly during the summer of 1917 to convince the German leaders to provide a framework for peace with the Entente, it was to no avail. The Kaiser and his general staff stubbornly held to their positions not wanting to give the appearance to the enemy that they lost the will to fight or were negotiating out of weakness. Charles Herber asserts that Kaiser Wilhelm’s immense ego was bruised in December 1916 when he was rebuffed trying to negotiate his own peace plan, “Now, the Kaiser asserted, only when the enemy leaders had been brought to their knees could he again think in terms of magnanimity.”[36] In the final analysis, the Germans had no desire to have the Vatican serve as a mediator. Pacelli was devastated at the impasse.[37] Meanwhile, events in Russia were beginning to unravel. Tsar Nicholas II abdicated the throne in March 1917 and by October, Lenin and the Bolsheviks were in control of the government and directing the war effort. To the Catholic Church, Marxism and Communism were warily viewed as atheistic political philosophies that posed a risk to the sovereignty of the Church.

This revolutionary foment would spill over into Germany after the war ended in November 1918. To the horror of Pacelli and the Catholic Church, socialist uprisings in Munich destabilized Germany’s largest state and the Bavarian Soviet Republic was declared. The next ten months would be a time of great economic instability and social unrest as the Bolsheviks threatened to spread Communism to other regions of the country. It was during this tumultuous period that Pacelli’s vehement anti-Bolshevik worldview was reaffirmed, a position he would hold throughout his future Pontificate. On April 29, 1919, Pacelli came perilously close to losing his life when members of the Red Brigade stormed the Nunciature in Munich and pointed a gun at his chest demanding use of the car. Pacelli held firm invoking the Church’s neutrality and was able to appease his attackers into returning the next day under more civilized conditions. It was during these dramatic events in Bavaria that Pacelli first exposed his perception of Jews and Bolsheviks. In a letter to Gasparri, Pacelli described a meeting his assistant Monsignor Schioppa had with Max Levien, head of the Munich government:

The scene that presented itself at the palace was indescribable. The confusion totally chaotic, the filth completely nauseating, soldiers and armed workers coming and going… Absolute hell. An army of employees were dashing to and fro, giving out orders, waving bits of paper, and in the midst of all this, a gang of young women, of dubious appearance, Jews like all the rest of them, hanging around in all the offices with lecherous demeanor and suggestive smiles. The boss of this female rabble was Levien’s mistress, a young Russian woman, a Jew and a divorcée, who was in charge…This Levien is a young man, of about thirty or thirty-five, also Russian and a Jew. Pale, dirty, with drugged eyes, hoarse voice, vulgar, repulsive, with a face that is both intelligent and sly.[38]

From the derogatory tone of this correspondence, it would certainly appear that Pacelli was anti-Semitic, but at this stage of the thesis, it is important to clarify the terms: anti-Judaism, anti-Semitism, and the classification of Jews as an inferior race as later espoused by the Nazis.

Anti-Judaism is the Christian response to the Jews rejecting Jesus Christ as the Messiah. It is a discrimination rooted in religious terms. Most early Christians were Jews but as the Apostle Paul preached the Gospel throughout the Roman world during the first century, Christianity took on more of a Gentile influence despite the fact that the Hebrew Scriptures were incorporated into the Christian Bible. Over the centuries, Jews were persecuted by Christians because they were looked upon as “Christ-killers” and “children of the devil.”[39] During the Middle Ages and beyond, Jews were accused of abducting Christian boys and using their blood for sacrificial purposes. Part of the Good Friday liturgy of the Catholic Church right up until 1959 included a prayer for the “perfidious Jews,” which read in part “Almighty and everlasting God, from whose mercy not even the treachery of the Jews is shut out: pitifully listen to us who plead for that blinded nation…Amen. [40] Thus, the Christian Church to this day, holds to the doctrine that Jews (and those of any other religious faith) must convert to Christianity in order to be saved. In A Moral Reckoning (2002), Daniel Jonah Goldhagen asserts that the Catholic Church was inherently both anti-Judaic and anti-Semitic:

For centuries, the Catholic Church, this pan-European institution of world hegemonic aspirations, the central spiritual, moral, and instructional institution of European civilization, harbored antisemitism at its core, as an integral part of its doctrine, its theology, and its liturgy. It did so with the divine justification of the Christian Bible that Jews were Christ-killers, minions of the devil.[41]

Anti-Semitism, as opposed to anti-Judaism, is an expression of hatred for Jews based on race. Goldhagen further explains the nature of anti-Semitism:

The term ‘anti-Semitism’ describes instances of persons thinking ill of, having animosity for, feeling enmity toward, or hating Jews simply because they are Jews or because those persons falsely attribute noxious qualities to their Jewishness and therefore to Jews in general.[42]

There is evidence to suggest that the Catholic Church tolerated a certain degree of anti-Semitism. An article on “The Jewish Question” published in the Catholic Augsburger Postzeitung on March 31, 1933 incorporated a statement of the Catholic Bavarian People’s Party deploring “the increasing ‘judaizing’ [Verjundung] of our intellectual, cultural, and scholarly life in Germany,” and further stating:

There is a certain kind of Jewish intellectualism which, despite its high intelligence, mixes with the German element in a destructive and baneful way. A people striving for national and intellectual renewal is reacting in a healthy manner when it opposes this admixture and demands that the German mind be thoroughly cleansed of Jewish influences.[43]

Throughout Western Europe especially in Austria and Germany, anti-Semitism was ingrained into the psyche of the people. A document that gained widespread circulation throughout the world during the beginning of the twentieth century was “The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion.” The document was purported to have been written at a secret meeting of wealthy Jews held in Paris in which they devised a conspiracy to take over the world. Jews were warily looked upon as a closed social structure with peculiar customs. In Europe, Jews were generally classified as Bolsheviks, Free Masons, or Capitalists who controlled financial markets. When the world staggered into an economic depression after the 1929 stock market crash, it was the Jews who were to blame. Jews were thus hated because of the assumed undue influence they wielded. Hitler exploited this theme in Mein Kampf:

The Jewish train of thought is, moreover, clear. The bolshevization of Germany, i.e. the extermination of the national folkish intelligentsia and the exploitation of German labor power in the yoke of world Jewish finance facilitated thereby, is thought of solely as a preliminary to a further extension of this Jewish tendency to conquer the world.[44]

Later in a speech to the Reichstag on January 30, 1939, Hitler would again link the Jews with the Bolsheviks but this time foment anti-Semitism to new levels as Jews were portrayed as an inferior race that only genocide could resolve:

I wish to be a prophet again today: should international financial Jewry in and outside of Europe succeed in plunging the nations once again into a world war, the result will not be the Bolshevization of the world and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe. [45]

This form of anti-Semitism was not only discriminatory but also dangerous as Christopher Browning explains: “The implications of racial anti-Semitism posed a different kind of threat. If previously the Christian majority pressured the Jews to convert and more recently to assimilate, racial anti-Semitism provided no behavioral escape. Jews as a race could not change their ancestors. They could only disappear.”[46] It is doubtful that Pacelli would have expressed his anti-Semitism to this level but his many years in Germany may have greatly influenced his perception of Jews beyond just their need for conversion to the Catholic faith. Browning notes how anti-Semitism was part of the culture of Germany in the early twentieth century, “By the turn of the century German anti-Semitism had become an integral part of the conservative political platform and had penetrated deeply into the universities.”[47] In the minds of Catholic ministers, Bolshevism had Jewish roots since many of the leading Soviet revolutionaries were Jews including: Leon Trotsky and Yokov Sverdlov not to mention one of the co-authors of the “Communist Manifesto,” Karl Marx.

The political unrest in Germany stabilized somewhat after the establishment of the Weimar Republic in August 1919. The office of Nuncio gave Pacelli the opportunity to nominate certain bishops that were considered “submissive to the Holy See”[48] such as Johannes Sproll (Rottenburg) and Konrad von Preysing (Eichstätt) who could be called upon at a later date to support Pacelli during the negotiation of the Concordat with Germany in 1933. In January 1922, Pope Benedict XV died and was replaced by Pope Pius XI. Pacelli’s mentor and close advisor Pietro Gasparri continued as Secretary of State. During the post-war period Pacelli continued to hone his diplomatic skills successfully negotiating Concordats with Bavaria (1924), Prussia (1929), and later with Baden (1932). This was not an easy task given the fact that most members of the German diplomatic corps were comprised of Protestants who looked down at minority Catholics as outsiders because of their allegiance to a Pope in Rome rather than a prelate in Germany.

Despite the perilous times of war, revolution, and social upheaval, Pacelli always expressed fond memories of his tenure as Nuncio to Germany. Those sentiments were attested to by the German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop who met with Pacelli during a state visit in March 1940. “Those years spent in the orbit of German culture represented perhaps the most delightful period of his [Pacelli’s] life and the Reich Government could be sure that he had a warm heart for Germany and always would have.”[49]

Pius XI took an autocratic approach to running Vatican affairs. Although Gasparri was asked to stay on as Cardinal Secretary, Pius XI feared that Gasparri was becoming too powerful of a figure within the Holy See especially after orchestrating the signing of the Lateran Accords with Mussolini in 1929. As such, the pope began searching for someone outside the walls of the Vatican to replace the seventy-seven year old Cardinal Secretary. In December 1929, he chose Eugenio Pacelli. Pacelli’s experience in German culture, language, and religion gave him marked precedence as Gasparri’s replacement just as the Nazi party was making political inroads in the German Parliament. Both Pius XI and Pacelli viewed Adolf Hitler as a potential partner in the struggle against the spread of world-wide atheistic Communism.

As previously noted, Pacelli’s family history of service to the Curia was instrumental in his appointment to serve in the office of the Vatican foreign ministry. His assignments working with Cardinal Gasparri, meeting with bishops throughout Europe, conferring with foreign heads of state during World War I, and, most importantly, his tenure as nuncio in Germany gave him the necessary diplomatic skills that would be needed to navigate the Church as Pope through World War II and beyond. While his intelligence and warmth helped propel him to the top of the Catholic hierarchy, his time spent in Germany also shaped his worldview on Communism and exposed him to the dark side of anti-Semitism.

As an endnote to this period in his ecclesiastical career, Pacelli met two men through a mutual friend in whom he would build lasting friendships riding horses in the German countryside. Those men were Wilhelm Canaris, the future Chief of German military intelligence (Abwehr) and General Ludwig Beck, Chief of the German General Staff both of whom would figure prominently in future plots to overthrow Adolf Hitler and later call upon Pacelli to act as a liaison on behalf of the German Resistance.[50]

### End Part II ###

References

[27] The Black Nobility refers to the Roman aristocratic families that backed Pope Pius IX during the overthrow of the Papal States in 1870 as part of the unification process of the Kingdom of Italy under Victor Emmanuel II. The Black Nobility dates back to the early Middle Ages when powerful aristocratic families such as the Orsini, Borghese, and Ruspoli moved to Rome to both support and benefit from a close association with the Vatican. [28] Frank J. Coppa, “Pius XII,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, http://www.britannica.com/biography/Pius-XII. [29] Cornwell, Hitler’s Pope, 42. [30] In 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus was a French artillery officer convicted of being a traitor for transferring military secrets to the Germans. Because he was Jewish and it was later determined that evidence that would have exonerated him was suppressed, the case divided France and touched off a wave of anti-Semitism and anticlericalism. In July 1906, the French court of appeals (Cour d’ Appel) ruled in his favor and Dreyfus was released from prison. [31] John S. Conway, The Nazi Persecution of the Churches 1933-1945(London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1968), 330. [32] Hubert Wolf, Pope and Devil, (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press, 2010), 64. [33] The T-4 Program was enacted by Adolf Hitler in October 1939 empowering doctors to legally euthanize people who were considered of no constructive use to the Third Reich, namely the permanently disabled, mentally handicapped, and the incurably ill among others. The Catholic Bishop of Münster, Clemons August von Galen protested vehemently and the program “officially” ceased in 1941 but not before an estimated 70,000 people were killed by starvation, lethal injections, or in gas chambers. [34] Charles J. Herber, “Eugenio Pacelli’s Mission to Germany and the Papal Peace Proposals of 1917,” The Catholic Historical Review Vol. 65 No. 1. (Jan. 1979), 27. [35] Wilhelm II, Emperor, The Kaiser’s Memoirs: Wilhelm II, Emperor of Germany, 1888-1918, English Translation by Thomas R. Ybarra, (New York: Harper, 1922), 263. [36] Herber, “Eugenio Pacelli’s Mission to Germany,” 25-26. [37] Herber, “Eugenio Pacelli’s Mission to Germany,” 29-30. [38] Cornwell, Hitler’s Pope, 74-75. [39] John 8:44. [40] Hubert Wolf, Pope and Devil, 84. The prayer for the “perfidious Jews” was part of the Good Friday mass liturgy found in the Roman Missal of 1570. The 3rd edition in the Latin and English version are quoted, pp 490-491. [41] Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, A Moral Reckoning (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002), 37. [42] Goldhagen, A Moral Reckoning, 21. [43] Martin Rohnheimer, “The Holocaust: What Was Not Said,” First Things (November 2003), http://www.firstthings.com/article/2003/11/the-holocaust-what-was-not-said. [44] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, English Translation, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1939), 906. [45] Adolf Hitler speech to the Reichstag, January 30, 1939. http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/docpage.cfm?docpage_id=2925 [46] Christopher R. Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939-March 1942, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 5. [47] Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution, 7. [48] Wolf, Pope and Devil, 54. [49] Documents on German Foreign Policy #668. “Record of the Foreign Minister and the Pope,”March 11, 1940. [50] Riebling, Church of Spies, 35.