Concordat with Germany – July 1933

“A Concordat,” according to historian George La Piana writing in 1940, “being patterned after an international agreement, implies the recognition by the state, of the sovereignty of the Holy See and of the supra-national character of the local Catholic Churches as part of a universal institution whose laws, hierarchy and absolute government are entrusted to the Pope.”[51]

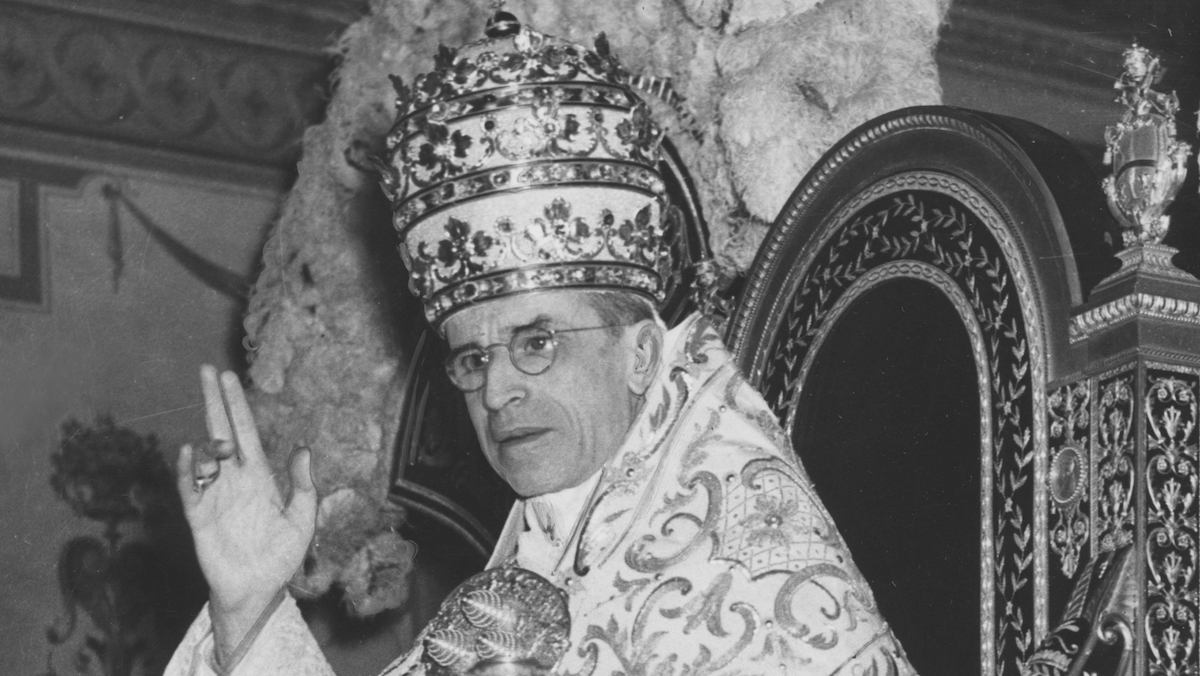

The July 1933 Concordat between the Catholic Church and Nazi Germany was one of Pacelli’s crowning diplomatic achievements as Secretary of State but an agreement that was doomed to failure before the ink even dried. Hitler wanted the support of the Catholic Center Party in his push to consolidate control of the government; the Vatican wanted certain safeguards against Nazi intrusions into Church affairs and its neutrality. Critics say Pacelli capitulated too easily to Nazi demands, while others insist that the Concordat was necessary to avoid the type of Catholic persecution suffered at the hands of von Bismarck during the Kulturkampf of the 1870s.[52] The larger question is why did the Catholic Church even consider entering into a formal agreement with the Nazis considering their reputation for brutality and Hitler’s proclaimed hatred of anyone who was not Aryan German, especially Jews?

Hitler’s Mein Kampf, was published in 1925 at a time when Pacelli was Nuncio to Germany. Surely, he must have either read the book or at least heard what was contained therein including the passage below as a glaring example:

I was convinced that this State [Austria] was bound to oppress and to handicap every really great German, as, on the other hand, it promoted everything non-German. I detested the conglomerate of races that the realm’s [Austria-Hungarian Empire] capital manifested; all this racial mixture of Czechs, Poles, Hungarians, Ruthenians, Serbs, and Croats, etc. and among them all, like the eternal fission-fungus of mankind – Jews and more Jews.[53]

In addition, Pacelli stationed in Berlin during the rise of the Nazi party in the 1920s, would have known Hitler’s reputation for hatred, street violence, and thuggery in his quest to become Chancellor of Germany. A handwritten note by Pacelli written during one of his meetings with Pope Pius XI dated April 1, 1933 is a telling sign of things to come, “Write to the Berlin Nuncio [Cesare Orsinigo] that further Jewish persons have reported to the Holy Father about the danger of anti-Semitic excesses in Germany, of which it is said that they have already occurred in some places.”[54] A now famous letter dated April 12, 1933 from Dr. Edith Stein, a converted Jew to Catholicism, addressed to Pius XI regarding persecution of the Jews in Germany was received by Pacelli on behalf of the pope. What is unknown is whether the pope actually read the letter; what is known is that the pope did not speak out against Nazi atrocities as Stein requested. In that correspondence, Stein wrote:

For years the leaders of National Socialism have been preaching hatred toward the Jews. Now that they have seized the power of government and armed their followers, among them proven criminal elements, this seed of hatred has germinated… We all, who are faithful children of the Church and who see the conditions in Germany with open eyes, fear the worst for the prestige of the Church, if silence continues any longer.[55]

Stein, also known as St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, was captured in the Netherlands and deported to Auschwitz where she died in 1942.

Despite these warning signs, and prodded by Cardinal Secretary Pacelli, Pius XI dispelled with his initial reservations about Hitler, telling the French Ambassador Charles-Roux in early March 1933: “I have changed my opinion about Hitler. It is the first time that such a government voice has been raised to denounce Bolshevism in such categorical terms, joining with the voice of the Pope.”[56] Pius XI (Achille Ratti) did not need much convincing from Pacelli. In 1918, the young Vatican librarian was sent to Warsaw by Benedict XV as his emissary to evaluate the post-war impact on Polish Catholics. During the early summer of 1920 while Ratti was nuncio, Poland was attacked by the Red Army and the citizens of Warsaw took up arms in defense and were able to stage a counter-offensive to repel the Bolsheviks.[57] So while Pacelli was nuncio in Munich fighting off intrusions by the Red Army, Ratti was in Poland meeting a similar fate. The experiences shaped the attitudes of both men in condemnation of Communism and Bolshevisim.

The Concordat signed with Nazi Germany was the culmination of a series of intense meetings and negotiations with various parties including: Hitler, Pacelli, German Ambassador to the Holy See Diego von Bergen, former German Chancellor Franz von Papen, and the head of the Catholic Center Party Ludwig Kaas. It was Kaas who in March 1933 was shuttling between Rome and Berlin negotiating with Hitler on behalf of Pacelli and the Vatican. According to Ernst–Wolfgang Böckenförde, Hitler also wanted an agreement with the Church:

Hitler’s assurances that he would maintain friendly relations between Church and State, and his readiness to conclude a concordat covering the areas of Church and school (for Hitler merely a political calculation), hit the German Catholics, therefore, in there most vulnerable spot and, from a political point of view, were bound to become a deadly temptation for them.[58]

Hitler desperately wanted the backing of Germany’s estimated 21.2 million Catholics[59] and was willing to make certain concessions. There were three essential bargaining chips that the Holy See had that could be used as an incentive for Hitler to agree to the Vatican’s terms: support for the Enabling Act, lifting of the ban on Catholics joining the Nazi party, and the dissolution of the Catholic Center Party and Bavarian People’s Party. The Center was a powerful political party that “consistently polling 12 to 13 per cent of the national vote” and “held the chancellorship in eight of the fourteen cabinets between 1918 and 1933.”[60] The Concordat outlined certain protections for the Catholic Church including the freedom to administer sacraments, collection of offerings, and autonomy to form and direct the activities of Catholic youth groups and associations. Guenter Lewy in his book The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany (1964) provides evidence that Kaas was holding meetings with Hitler and von Papen prior to the Enabling Act vote of March 23, 1933.[61] The backing of the Catholic Center Party was essential to Hitler securing absolute control over the government. For this reason, Hitler outlined his intended relationship with the church in a speech to the Reichstag on March 23, 1933:

The National Government perceives in the two Christian confessions the most important factors for the preservation of our Volkstum. It will respect any contracts concluded between these Churches and the Länder. Their rights are not to be infringed upon. But the Government expects and hopes that the task of working on the national and moral regeneration of our Volk taken on by the Government will, in turn, be treated with the same respect…The Government’s concern lies in an honest coexistence between Church and State; the fight against a materialist Weltanschauung [worldview] and for a genuine Volksgemeinschaft [people’s community] equally serves both the interests of the German nation and the welfare of our Christian faith…The rights of the Churches will not be curtailed and their position vis-à-vis the State will not be altered.[62]

Five days later, at the annual Fulda Conference of German Bishops, Cardinal Adolf Bertram “joined the camp of those bishops who were in favor of withdrawing the various prohibitions imposed on the Nazi Party.”[63] What is surprising is that the German bishops who were so adamantly opposed to Nazi ideology prior to March 1933 would suddenly embrace Hitler and back the regime. The same holds true for most leaders of the Center Party who “stood in the very forefront of the battle against the National Socialists in the election of March 5, 1933”[64] and yet dissolved the political party after the signing of the Concordat. Since Pacelli was the driving force behind the March negotiations with Germany, it could be argued that he was able to exercise his influence over the German bishops and the Center Party politicians in order to get them to comply for the sake of signing the Concordat. However, in an interesting footnote in Böckenförde’s 1961 journal article “German Catholicism in 1933,” he quotes Pius XII’s private secretary Robert Leiber who conveyed Pacelli’s surprise on hearing of the German bishop’s decision to allow Catholics to join the Nazi party, “Why must the German bishops come to terms with the government so quickly? If it must be done, couldn’t they wait a month or so?”[65] It could be argued that Pacelli was perturbed that the German bishops capitulated less than a week after the Enabling Act was signed without consulting him. Now, an important bargaining chip in Pacelli’s negotiations of a Concordat with Hitler was off the table.

Once the Concordat was signed by Pacelli and von Papen on July 20, 1933, all Catholic political parties were dismantled and dissolved. Böckenförde notes the significance of the agreement, “At the moment that Hitler stated that he would respect ‘Christian principles’ the Catholics on the basis of their political principles lost all interest in defending the Weimar State.”[66] In a meeting of a Conference of Nazi Ministers dated July 14, 1933, Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick recorded in his notes the surprise that the Führer expressed about the willingness of the Vatican to sign the Concordat.[67]

The Reich Chancellor saw three great advantages in the conclusion of the Reich Concordat:

- That the Vatican had negotiated at all, considering that it operated, especially in Austria, on the assumption that National Socialism was un-Christian and inimical to the Church.

- He, the Reich Chancellor, would have thought it impossible even a short time ago that the Church would be willing to obligate the bishops in this state.

- That with the Concordat, the Church withdrew from activity in associations and parties e.g. also abandoned the Christian labor unions…Even the dissolution of the Center Party could be termed final only with the conclusion of the Concordat, now that the Vatican had ordered the permanent withdrawal of priests from party politics.

- That the objective which he, the Reich Chancellor, had always been striving for, namely an agreement with the Curia, had been attained so much faster than he had imagined even on January 30; this was such an indescribable success that all critical misgivings had to be withdrawn.

Pacelli did have other motivations for aligning with the Nazis in 1933. The party had a strong anti-Marxist platform that was appealing to both Pacelli and Pope Pius XI.

Article 16 of the Concordat is an interesting accommodation in regard to the absolute allegiance to the Reich by Catholic bishops:

Before the bishops take possession of their dioceses they shall take an oath of allegiance either before the Reichsstatthalter of the appropriate province, or the Reich President as follows: ‘I swear and promise before God and on the Holy Gospel, as befits a bishop, loyalty to the German Reich…I swear and promise to respect, and to have my clergy to respect, the constitutionally constituted government.’ [68]

It could be argued that if the Vatican was truly neutral in regard to the Reich, no oath would be necessary. Once the agreement was signed, however, the Nazis began to violate many of the stipulations. An appeal written by the Reich youth leader Baldur von Shirach dated 15 March 1934 to the Catholic youth gives an indication of the pressure that the Reich exerted on the Catholic youth:

Catholic youth! You run the risk of being looked upon as saboteurs by the German people some day, as your negative attitude could be interpreted as eccentricity and obstinacy. There is still time, the question is still unanswered, the question after the ‘Why’, which waits for its answer…Catholic youth, do you want to adhere stubbornly to your special viewpoint, do you want to be branded in the judgement of history as the destructive force which sabotaged the unity of the Reich and the formation of its future?[69]

On the infamous Night of the Long Knives of June 30, 1934 it was not just Nazi party members who were purged, so too were prominent Catholics. Franz von Papen’s press secretary was gunned down, the President of Catholic Action Dr. Erich Klausner as well as his deputy Edgar Jung were killed, Dr. Fritz Gerlich, editor of the anti-Hitler magazine Straight Path was beaten to death, Adalbert Probst, the national director of Catholic Youth Sports Association was shot to death, as well as Father Bernhard Stempfle who denounced Hitler.[70] The New York Times reported in June 1937 about the continued Nazi abuses of the agreement:

Hence the gradual extinction of Catholic schools despite the concordat signed soon after National Socialism attained supreme power; hence the suppression of Catholic youth societies and the imprisonment of their leaders despite the promise of toleration which the concordat contained…If the concordat had been adhered to, there would have been no subsequent trouble. It is notorious, however, that it has been so openly and flagrantly violated that it is now a dead letter. [71]

Thus, Pacelli’s crowning diplomatic achievement as Cardinal Secretary in 1933 resulted in an utter failure. Pope Pius XI was livid and it was in March 1937 that he released his scathing encyclical “Mit Brennender Sorge.” As David Kertzer notes, when Hitler heard about the encyclical he was incensed and threatened to disgrace the church and “reveal graphic tales of sexual abuse by Catholic clergy” moving “quickly to gather incriminating evidence.”[72]

Can Pope Pius XI and Cardinal Secretary Pacelli be faulted for entering into an agreement with Hitler in order to protect the Church’s interests in Germany and avoid another Kulturkampf? Hitler was a Catholic, Germany was a Christian nation, and the Nazi Party was a staunch enemy of Bolshevism. It does not seem unreasonable that Pacelli would want to document certain protections for the Church but to sacrifice the Catholic Center Party which posed at least a semblance of political opposition against unfettered Nazi nationalism seemed to be a high price to pay. To infer that Pacelli was therefore pro-Nazi by signing the Concordat would be a misinterpretation of the facts. Unfortunately, Pacelli could not have foreseen in early 1933 that he made a pact with the devil.

Vatican Neutrality

“The neutrality of the Holy See,” wrote Pope Pius XII on July 20, 1943 to President Franklin Roosevelt, “strikes its roots deep in the very nature of our Apostolic ministry, which places us above any armed conflict between nations.”[73] Dan Kurzman agrees that the general consensus among scholars is that Pius XII tried to maintain the neutrality of the Church at all costs, “Pius was mainly driven, many believe, by an obsessive desire to preserve the power and earthly trappings of the Church at almost any cost; and he used neutralist policy to achieve this end.”[74] It was Pius XII’s desire to maintain Vatican neutrality that Frank Coppa states as the reason why he refused to release a letter of condemnation drafted by Vatican Under- Secretary Dominico Tardini in May 1940 when Germany invaded Belgium, Holland and Luxemburg. “Instead he chose to dispatch less-threatening and potentially less-dangerous messages of sympathy to their rulers, in order to preserve his impartiality.”[75]

Pius XII knew that in order to have any chance of brokering a peace agreement with the belligerents, the Vatican had to maintain neutrality. In reality, however, was the Vatican financially compromised in supporting the Italian and German war effort?

When the Lateran Accords were signed in February 1929 by the newly installed Fascist regime in Italy, the treaty recognized Vatican City as an independent sovereign nation. As part of the agreement, the Italian government paid the Catholic Church 750 million lire in cash and another one billion lire in Italian government bonds as restitution for the permanent divestiture of the old Papal States.[76] Since most of the compensation was paid in the form of government securities, a collapse of the Italian economy would essentially make the bonds worthless. While the financial considerations of the agreement did not pose an immediate conflict of interest when the agreement was signed in 1929, it did, however, become a problem for Pius XII when Italy joined the war on the side of Nazi Germany in June 1940. Did Pius XII temper his criticism of Mussolini and the Fascist government out of financial necessity? Needless to say, during war, contributions to the Catholic Church were significantly reduced because of economic disruptions in the marketplace;[77] therefore, any reduction in the value Italian bonds would certainly impact Vatican finances. Whether this was indeed a consideration of Pius XII is difficult to ascertain but having Italian debt as part of the Vatican investment portfolio during war would certainly give the appearance of a conflict of interest and thus compromise neutrality.

Similarly, the signing of the Concordat between the Catholic Church and Nazi Germany in July 1933 presented another arrangement rife for a conflict of interest. In keeping with a long standing German policy dating back to the early nineteenth century, the Nazi government assessed a church tax or Kirchensteuer on the income of Christian citizens which was then turned over to the churches to cover the costs of operations in Germany. In 1943 alone, the revenue received by the Catholic Church from the Kirchensteuer was in excess of $100 million ($1.7 billion in 2014 dollars).[78] Clearly, this accommodation to the church would put the Pope in a compromised position for fear that the Nazis would cease making payments if he openly criticized leaders of the Reich.

In June 1942, the money manager for the Vatican, Bernadino Nogara, convinced Pacelli to approve the formation of the Vatican Bank (IOR). The IOR was later accused of secretly accommodating money transfers from the German Reichsbank through Swiss intermediaries for the purchase of goods and materials for the war effort.[79] Whether the pope was aware of these transactions is unknown.

Patricia M. McGoldrick argues that the Vatican was anything but neutral when it came to investing Church funds during the war. Her research shows that the Vatican used primarily New York banks (J.P. Morgan and City Bank) as safe havens for cash and gold reserves to fund the world-wide operations of the church. The Vatican used these funds not only to provide relief to local dioceses throughout the world but also to purchase food to feed thousands of starving residents in Rome during the German occupation. McGoldrick concludes that if the Vatican was pro-German, it would have invested its funds in the German banking system. Instead, it relied on American banks and Barclays in London, “Thus the concomitant argument must be allowed: that the Vatican transferred its assets and the financial administration to the USA for the duration of the war must be accepted as compelling evidence of its pro-Allied and pro-democracy sympathies, and of its special relationship with the United States.”[80] Whether the investment of Vatican gold and other assets into the United States is “compelling evidence of pro-Allied and pro-democracy sympathies” is debatable but Nogara as a savvy investor knew that the United States was probably the safest place to hold assets during the war.

The Vatican’s involvement in disrupting relations between Germany and Italy is also attested to in a memorandum by an official (Schmidt) of the German Foreign Minister’s Secretariat dated October 18, 1941:

England was obviously intent upon sowing discord between Germany and Italy. Her propaganda was concentrated in Italy, and we had confirmation of this through an instruction which became known to us. With the partial utilization of the Vatican, false reports were being spread by countless agents throughout Italy for the advancement of this propaganda.[81]

There is no question that Pius XII was not pleased when Mussolini declared war on the Allies in June 1940. As such, the pope was forced to make a decision what to do with foreign ministers of Allied countries that were living in Rome outside the Vatican compound. Pacelli the diplomat, realized that if he had any chance of serving as an intermediary of a peace initiative, he would best be served by having Allied diplomats nearby. Therefore, accommodations were made inside the Vatican for Allied embassies including the American and British.

The pope also wanted open access to the Allies during his secret negotiations with the German Resistance.

Assassination Attempts on Hitler and the German Resistance

In Church of Spies (2015), Mark Riebling makes a compelling case that the legacy of Pius XII and his controversial position of “silence” pertaining to the persecution of the Jews, will continue to be misconstrued unless consideration is given to his actions done in “secret:”

Those who later explored the maze of his policies, without a clue to his secret actions, wondered why he seemed so hostile toward Nazism, and then fell so silent. But when his secret acts are mapped, and made to overlay his public words, a stark correlation emerges. The last day during the war when Pius publicly said the word “Jew” is also, in fact, the first day history can document his choice to help kill Adolf Hitler.[82]

Riebling provides important details about how Pius XII got involved with the German Resistance movement and was privy to and condoned plans by German generals to assassinate Hitler and overthrow the government. For a sitting pope to be even peripherally involved in plots to remove a head of state is not only unprecedented but extremely dangerous. Patricia McGoldrick also attests to the Pope’s participation in the conspiracy:

Pius XII had previously exhibited an equally surprisingly pragmatic side to his character when, once his efforts to prevent war had failed, he took the astonishing decision, within weeks of the invasion of Poland, to co-operate with German conspirators plotting to assassinate Hitler, restore democracy to Germany, return independence to Poland, and sue for peace with Great Britain and France.[83]

Adolf Hitler had the uncanny ability of surviving various life threatening situations including numerous assassination attempts. During World War I, he was twice seriously injured requiring hospitalization. While his second injury in 1918 ended his military career, his charismatic personality, his thunderous oratory, and his insatiable political ambitions quickly stoked the fires of a national movement. A third close call occurred in 1923 during a massive demonstration on the streets of Munich. The man linking arms next to Hitler (Erwin von Scheubner-Richter) was shot and killed. As Ian Kershaw notes, a stray bullet could have changed the course of history.[84] In August 1939, two days before the German invasion of Poland, a distraught Deputy Foreign Minister Ernst von Weizsäcker met with Hitler in a futile attempt to dissuade him from ordering the offensive. Weizsäcker had a Luger hidden in his pocket intending to shoot Hitler and then himself but “he lost his nerve and left in a sweat.[85] In November 1939, Hitler left a party rally early after giving a speech at the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich in order to catch a train back to Berlin. Minutes later, a bomb planted near the dais detonated killing eight and injuring sixty-three others.[86] Ironically, Hitler received a congratulatory letter from Pope Pius XII for surviving the blast.[87]

These early attempts on the life of Hitler did not involve the Pope but at the time of the beer hall assassination attempt in 1939, there was growing discontent among certain German generals including: Chief of Staff Ludwig Beck, Erwin von Witzleben, and Hans Oster who were alarmed by the blatant Nazi brutality in Poland and Hitler’s grand designs for conquering the rest of Europe. The conspirators, led by Wilhelm Canaris at the Abwehr, were determined to find an intermediary of unquestionable character and authority who would contact the British on their behalf and insure that once Hitler was removed, the Allies would recognize the newly installed Reich leadership and negotiate for peace. Canaris chose his old riding partner Pope Pius XII. The question then became who would contact the Pontiff to see if he would be willing to support the coup and contact the British? The man chosen was Josef Müller.

Josef Müller was a lawyer and a devout Catholic who lived in Munich and had a reputation for getting things done. Mary Gloria Chang explains why Müller was selected for the task, “Müller’s record of resistance to the Nazis and his legal work on behalf of Catholic institutions earned him the trust of Cardinal Pacelli, who sometimes consulted him about Hitler’s foreign policy.”[88] Müller also had close ties to Monsignor Ludwig Kaas, the former chief of the German Center Party and close advisor to the Pope, and Robert Leiber, the pope’s personal assistant. Canaris contacted Müller and convinced him to join the Abwehr as a special agent in charge of acting as a liaison with the Vatican. As Chang notes, Müller would serve as a double agent:

In a plan that came to be known among the conspirators as “Operation X,” Müller assumed the cover of an Abwehr reserve officer with the intelligence assignment of discovering political developments in Italy. His real mission was to communicate messages to Britain through the Vatican, with the ultimate objective of obtaining acceptable peace terms for a post-Hitler government.[89]

From 1939 to 1943, there were various plans to stage coups or assassinate Hitler but the generals lost their will and Hitler remained in power. Chang explains why there was some reluctance to proceed, “The failure of the generals to embrace the plan was due to a combination of fear of being accused of treason, Hitler’s popularity, their personal military oath, and lack of faith in the goodwill of the Allies.”[90]

As the year 1943 began, the Pope was alerted that a new plot to kill Hitler was in the planning stages. On March 13, Hitler boarded a plane back to Berlin after meeting with his generals in Smolensk at the eastern front. As Lieutenant-Colonel Heinz Brandt approached the tarmac as part of Hitler’s entourage, he was stopped by General Fabian Schlabrendorff who asked if he would be willing to deliver a box of cognac to General Helmuth Stieff when he arrived in Berlin. Brandt agreed but little did he know that inside the package was a bomb that was ignited and timed to explode shortly after takeoff. The bomb never detonated.

A few days later, Colonel Baron Rudolf von Gersdorff was scheduled to be at the Heroes’ Day Ceremony in Berlin where Hitler would be in attendance. Despondent after his wife’s death, von Gersdorff promised to detonate a bomb he had hidden in his pocket. When Hitler left the ceremony earlier than planned, von Gersdorff ran to the bathroom and disconnected the device.

By far the most famous assassination attempt was the Valkyrie bombing in July 1944. Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg attended a meeting with Hitler and staff generals at the Wolf’s Lair. Upon arrival, Stauffenberg slid his briefcase packed with explosives next to Hitler and walked out of the meeting supposedly to answer a phone call. Once outside, the explosion ripped a wall out of the lair but Hitler survived the blast, startled, but unscathed. The fallout of the failed assassination attempt was extensive and brutal. Conspirators including Stauffenberg, Oster, and Canaris were all executed. Hundreds of other co-conspirators were hanged. General Beck committed suicide. A report prepared by Ernst Kaltenbrunner of the SS also named Eugenio Pacelli as a co-conspirator. The Gestapo claimed that Müller was involved in the plot and passed information through a network inside the Vatican. An excerpt from the report outlines those responsible for the plot to kill Hitler:

Canaris and Oster were in contact with the Pope through the former Munich lawyer Dr. Josef Müeller (sic) who was made an agent of the Counterintelligence. Müeller, through Monsignore Neuhaeusler, was introduced to the former Cardinal Secretary of State Pacelli and was married by him in the Crypt of St. Peter’s. Since this was quite an exception, he had a certain reputation in Vatican circles. Müeller then met Pacelli several times and built up a good personal relationship which was used for political conversations. Pacelli was always especially open and kind to him. Müeller then, during the war and already in the fall of 1939 contacted the Jesuit Father Leiber, the personal secretary of the pope. From Leiber he received a lot of information on the position of the Pope and the enemy powers. He also talked with him about a possible move toward peace, when Leiber made clear to him that the condition for a negotiation about peace is a regime change in Germany. Through Leiber, Müeller came in contact with English and American circles, especially with the American Taylor…[91]

Although Müller was arrested by the Gestapo in the Valkyrie plot and sat on death row along with others including the Protestant Pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Müller survived his imprisonment. After sitting on death row at Flossenbürg and then Dachau, Müller was eventually liberated by American troops after the SS drove a group of prisoners to the mountains of Italy and released them.

It is important to note that the Pope made every attempt to insulate himself from being accused of having any involvement in the overthrow of a national leader no less an assassination attempt. For this reason, he used subordinates to meet with Müller for updates. It was Müller who advised the Pope to keep a low profile lest Hitler retaliate with his arrest. While his role as intermediary of the German Resistance movement does not exonerate Pacelli for not speaking out against Nazi war crimes, it does shed light on the risks that the Pope was willing to take in order to stop the madness of Adolf Hitler.

### End Part III ###

References

[51] George La Piana, “The Political Heritage of Pius XII,” Foreign Affairs, Vol.18 No.3 (Apr 1940), 489. [52] John S. Conway, The Nazi Persecution of the Churches 1933-1945, 22-23. [53] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, 160. [54] Wolf, Pope and Devil, 132. [55] Edith Stein, Letter to Pope Pius XI, April 12, 1933. http://jcrelations.net/Edith+Stein+letter. [56] Kertzer, The Pope and Mussolini, 200. [57] Kertzer, The Pope and Mussolini, 14. [58] Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde, “German Catholicism in 1933,” CrossCurrents Vol. 11 No.3 (Summer 1961), 297. [59] German History in Documents and Images, Vol. 6 http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-c.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=4374. [60] Guenter Lewy, The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany, (Boston: DaCapo Press, 1964), 5. [61] Lewy, The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany, 65. [62] Adolf Hitler Speech to Reichstag March 23, 1933, http://www.worldfuturefund.org/Reports2013/hitlerenablingact.htm. [63] Lewy, The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany, 37. [64] Böckenförde, “German Catholicism in 1933,” 285. [65] Böckenförde, “German Catholicism in 1933,” footnote #9, 287. [66] Böckenförde, “German Catholicism in 1933,” 300. [67] German History in Documents and Images, “Excerpt From the Minutes of the Conference of Ministers on July 14, 1933. http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=1499 [68] Reich Concordat between the Holy See and the German Reich (July 20, 1933), Article 16.German History in Documents and Images. http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_image.cfm?image_id=3205 [69] Baldur von Shirach, “Appeal to the German Catholic Youth,” March 15, 1934, as quoted in Appendix #6, The Nazi Persecution of the Churches by John S. Conway, 359. [70] Riebling, Church of Spies, 58-59. [71] Wireless to The New York Times, “Nazis War on Catholic Church To Make Dictatorship Complete,” The New York Times (June 1, 1937), 8. [72] Kertzer, The Pope and Mussolini, 260. [73] Pope Pius XII, Letter to Franklin Roosevelt, July 20, 1943, .http://docs.fdrlibrarary.marist.edu/PSF/BOX52/t468q01.html. [74] Dan Kurzman, A Special Mission: Hitler’s Secret Plot to Seize the Vatican and Kidnap Pope Pius XII, (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2007), 120. [75] Coppa, “Between Morality and Diplomacy, 558-559. [76] Kertzer, The Pope and Mussolini, 107. [77] Posner, God’s Bankers, 111-112 footnote. [78] Posner, God’s Bankers, 111-112 footnote. [79] Posner, God’s Bankers, 119. [80] Patricia M. McGoldrick, “New Perspectives on Pius XII and Vatican Financial Transactions During the Second World War.” The Historical Journal Vol.55 No.4 (2012), 1044. [81] Documents on German Foreign Policy, No. 409, “Record of the Conversation Between the Foreign Minister and Ambassador Alfieri at Headquarters, “ October 17, 1941. [82] Riebling, Church of Spies, 28. [83] McGoldrick, “New Perspectives on Pius XII,”1045. [84] Ian Kershaw, Hitler: 1889-1936 Hubris (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999), 211. [85] Riebling, Church of Spies,32. [86] Ian Kershaw, Hitler: 1936-1945 Nemesis (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000), 273. [87] Riebling, Church of Spies, 76. [88] Mary Gloria Chang, “The Vatican and the German Resistance During World War II: 1939-1940, “The Catholic Social Science Review, Vol. 14 (2009), 387. [89] Chang, “The Vatican and the German Resistance”, 387. [90] Chang, “The Vatican and the German Resistance”, 394. [91] The Kaltenbrunner Report, November 29, 1944, English translation by Michael Hesemann, as it appeared in Pope Pius XII and World War II: The Documented Truth by Gary L. Krupp, 23.