The economy of the U.S. of A. has struggled for the last ten years. To say this, is probably the greatest understatement uttered over the last five centuries or so. It started with the real estate fiasco and the resulting financial crisis and continued for another eight years due to inept and misdirected economic policies.

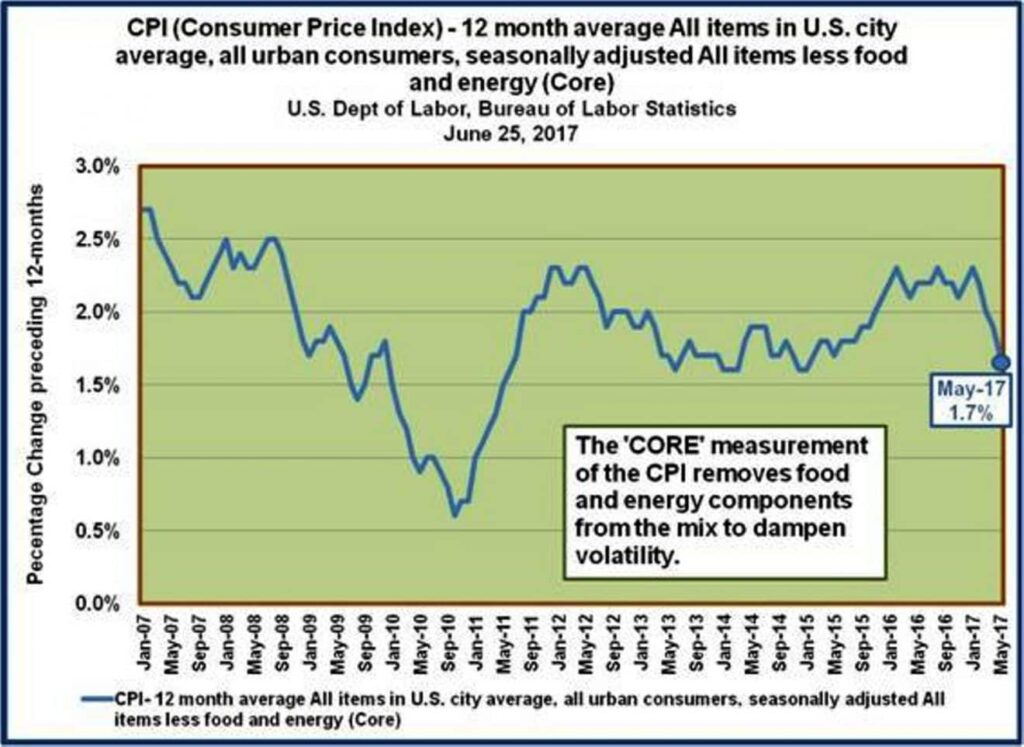

The FED’s obsession with inflation fears has not been due to inflation or any threat of inflation at least of the demand pull variety. To make things worse, the FED (Federal Reserve System, our central bank), and especially its’ monetary policy making body, the FOMC or Federal Open Market Committee, has lowered even further its tolerance for inflation, moving its’ target downward to 2%. Regarding this, the FOMC has stated:

“The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) judges that inflation at the rate of 2 percent (as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, or PCE) is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve’s mandate for price stability and maximum employment.”

According to a 2012 press release, the Fed noted:

“The inflation rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy, and hence the Committee has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for inflation. The Committee judges that inflation at the rate of 2 percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate.”

Note: the “Committee” is in reference to the FOMC, or Federal Open Market Committee.

Whatever happened to the FED’s concern for high employment and a rise in median incomes, as well as a brighter future for our youth?

Dr. Yellen, ‘tear down this wall’ of obsessive fear of inflation

In a previous essays, we have pointed out that the decision to pay interest on legal reserve deposits of depository institutions, whether required or in excess, has become, though in a limited way, a new tool of monetary policy. Hence, this new policy tool, while having been debated since the FED’s inception, has become an additional tool for influencing interest rates in the economy at large.

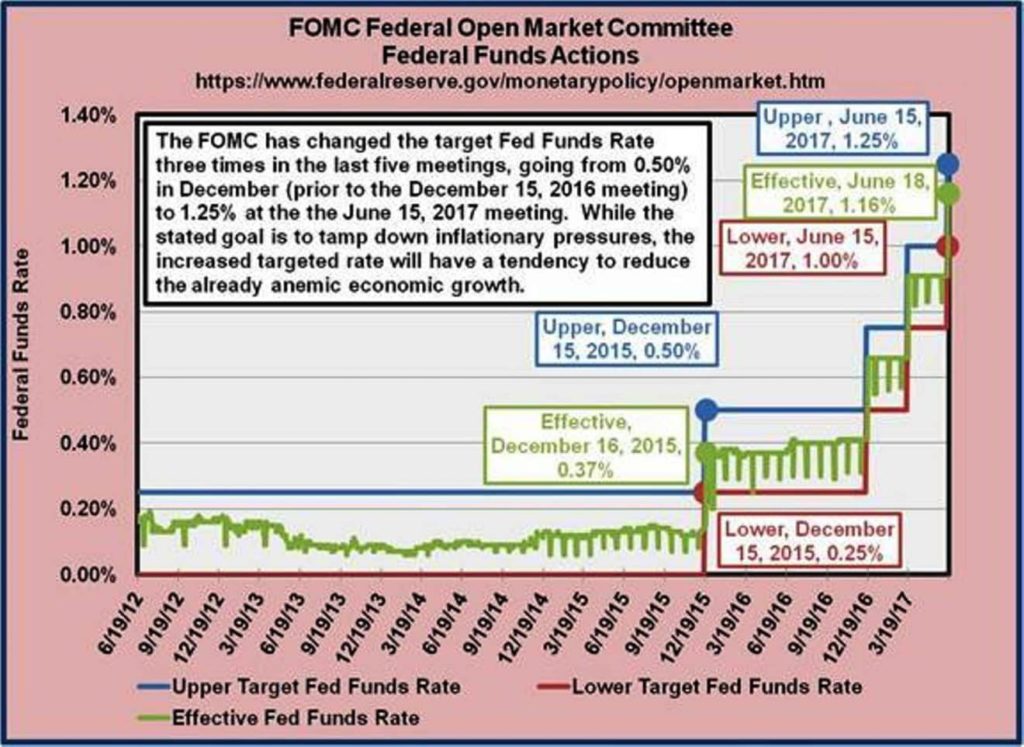

In our essay, What’s Up with the Federal Reserve??, we stated that: ”In a ‘normal’ environment, the FOMC would set a targeted Fed Funds Rate and the NY Fed would take the necessary steps in the secondary US Treasury Securities markets to drive the rate in the desired direction. If the FOMC wanted to drive up the rate, the NY Fed would sell securities (or simply buy fewer securities than would otherwise be the case), causing interest rates to rise due to the increased availability of securities. Conversely, if the FOMC directed the NY Fed to drive down the Fed Funds Rate, they would purchase securities from dealers in the secondary markets. In 2011, the FED instituted a policy tool wherein they would pay interest on depository reserves at the upper targeted Fed Funds Rate.”

Drilling down on Price Level Changes: Demand Pull and Cost Push

There are two major causes of price level change, demand pull and cost push. The FED’s recent actions in raising interest rates, the latest on June 15 of this year, seems to imply that a bout of fairly serious inflation is just around the corner. A few FED officials point to the labor market and argue that it is in good shape and further increasing pressures on the labor market due to demand pull pressures from household and business spending will result in an inflation rate beyond the now acceptable rate of 2%.

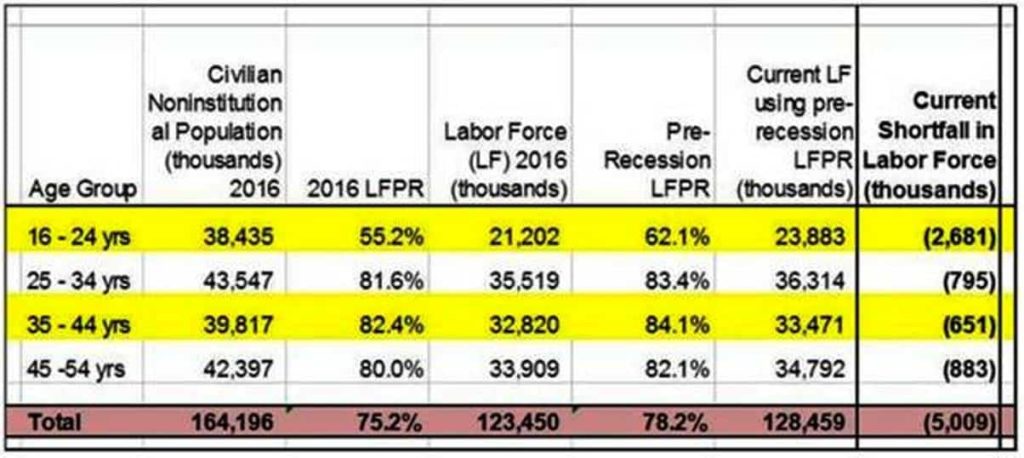

Previously, we have argued that this optimistic view of the labor market is a misinterpretation of the current labor market’s condition due to a large amount of discouraged workers in the younger end of age distribution from 16 to 54 years of age and especially the group from 16-24, and that any improvement in the economy’s outlook would lead to a significant growth in the labor force participation rate due to an encouraged worker affect.

If a bout of demand pull inflation (or deflation) occurs when elements of aggregate demand expands (or contracts) too rapidly causing the markets involved to experience price increases (or decreases) in an attempt to affect the growing (or shrinking) scarcity of the good or service in question, the FED has shown over the years that is has ample tools to cope rather easily with the problem.

If however, a bout of cost push inflation or deflation occurs, the FED, as seen at various times from 1973 to 2001, would face a much tougher challenge in reducing such inflationary pressures.

An example of this type of demand pull price level change occurred in the post-WWII period, when price controls were finally eliminated and the Korean War began. Several demand pull factors arose, such as pent-up consumer demand due to years of wartime rationing and the stoppage of the production of passenger cars for a few years during WWII all contributing to pushing prices higher. Demand pull inflation occurs in the product markets for goods and services and it is fairly easy for the FED to control with its current arsenal of monetary policy tools.

Cost push inflation occurs in the markets for productive resources (labor, debt and equity capital, entrepreneurship, and land). It is a much more difficult type of inflation for the FED to control than is the demand pull type of inflation.

A relatively recent example of this type of inflation was the period from 1993 through 2000. In this case, it was the productive resource, land, in the form of crude oil prices. The cartel, OPEC, doubled the existing price from $15 per barrel to $30 per barrel. This was nothing new; OPEC had initially quadrupled the per barrel price from $3.50 to $14 in 1973, marking their assumption of pricing and production decisions formerly relegated to the so called Seven Sisters, the major oil companies comprising the relatively benign oil cartel prior to OPEC’s takeover of pricing and production decisions.

The source of that oil shock can be laid on the doorsteps of the Anti-Trust Division of the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission. Their inaction allowed 12 large U.S. oil companies to become four, sealing the economies doom to these record oil prices.

The FED: Efficacy of Monetary Policy in addressing Inflationary Concerns from the Demand Side and the Supply Side

The coping costs for the economy of the FED’s monetary policies in controlling each type of price level change differs significantly. The FED’s monetary policy tools such as discount rate changes and open market operations are geared to controlling aggregate demand rather than aggregate supply. The FED relies heavily upon the control of the growth rate of money, credit and thus interest rates which are more effective in controlling the behavior of the spenders such as households and business and much less effective in controlling the behavior of the productive resources such as labor, land, and entrepreneurship.

In this presentation, the aggregate supply relates to the economy’s overall output of the productive resource mix (labor, capital, entrepreneurship and land). This would include output from foreign sources as well, i.e., imports.

Allowing the growth rate of real Gross Domestic Product to reach 3 or 4 percent and even 5 for a short while would enable a breakout of the economy from the persistent slow growth rate we have witnessed since the financial crisis peaking around 2008.

Unacceptably high price level increases of the demand pull type such as a rapid expansion in the household and business sectors, could be slowed fairly easily with existing tools of monetary policy if such a price level increase was of the demand pull type as would most likely be the case.

Regarding cost push price level changes, these price level changes emanate from the markets for productive resources such as labor and land. Labor unions and OPEC are cartels. Labor and crude oil are productive resources. By controlling supply they can control price whether you call it the labor compensation rate or the price of a barrel of crude oil.

Speaking of Supply Side: Let’s Talk Minimum Wage

The minimum wage is another example although it is put into place through government legislation. If the cartel price or legislatively determined minimum wage is below the true market price, it is ineffective. If the cartel price is above the market price, it is effective and is maintained by the control of supply by either the cartel or government legislation. This leads to the significant difference between the demand pull and cost push types of price level change.

To suppress cost push inflation with existing monetary policy tools, aggregate demand must be depressed leading to an even greater fall in the equilibrium quantity whether it is in the form of hours of labor or barrels of crude oil.

This was not the case with demand pull inflation. This should wave a very large red flag to those espousing more legislation to increasing the minimum wage. As the minimum wage on entry level jobs rises, physical capital has replaced entry level labor jobs and these jobs disappear as we are seeing at fast food stores.

These entry level jobs enabled young adults to learn the most basic skills for being successfully employed and college bound younger adults to earn incomes to help pay the rapidly rising cost of attending college whether it be private or governmentally attached institutions of higher learning. This may be a major cause of the weak growth in the number of those attending such institutions.

Another Supply Side Issue: Fracking

The end of fracking would have more widespread negative effects on the economy. If fracking were ended, the price of electricity which fell and continues to fall as fracking becomes more widespread, would rise again. As is currently the situation, the increased quantity supplied from fracking fields such as Marcellus, have driven the price of electricity down and reduced carbon emissions as this occurs.

The price for a KWH should continue to fall as stranded costs from the conversion of coal and oil to natural gas are fully absorbed. This will cause an even further decline in the price of electricity.

Ending fracking would reverse this process and result in a switch back to using coal and oil. As this occurs, the cost of generating electricity would rise, resulting in the rise in the price of electricity. Accompanying this rise in the price of electricity will be a rise in carbon emissions. In turn, stranded costs due to the switch back from natural gas to coal and oil should help cause a further rise in the price of electricity.

These are but two of the many possibilities highlighting the fallout from the lack of thorough analysis leading to unintended consequences and the like. As the old expression goes, “Talk is cheap”, to which we add, the cost of bad policies can lead to enormous and unnecessary burdens.