Recently, while researching Washington, D.C. history, I came across a local school named after a Myrtilla Miner. The first name sounded like one of those 19th century names no longer in use. Might there be some old city history involved? Yes, actually—–Miner Elementary School is the direct institutional descendant of a school founded here in 1851 by Miss Miner.

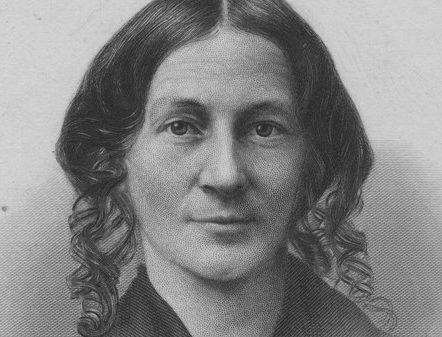

Miss Myrtilla Miner was a mid-19th century white teacher, strong-willed and religious, but physically frail, who founded a school originally for poor black girls in Washington, despite threats on the one hand and tight budgets on the other. Her life’s work continues.

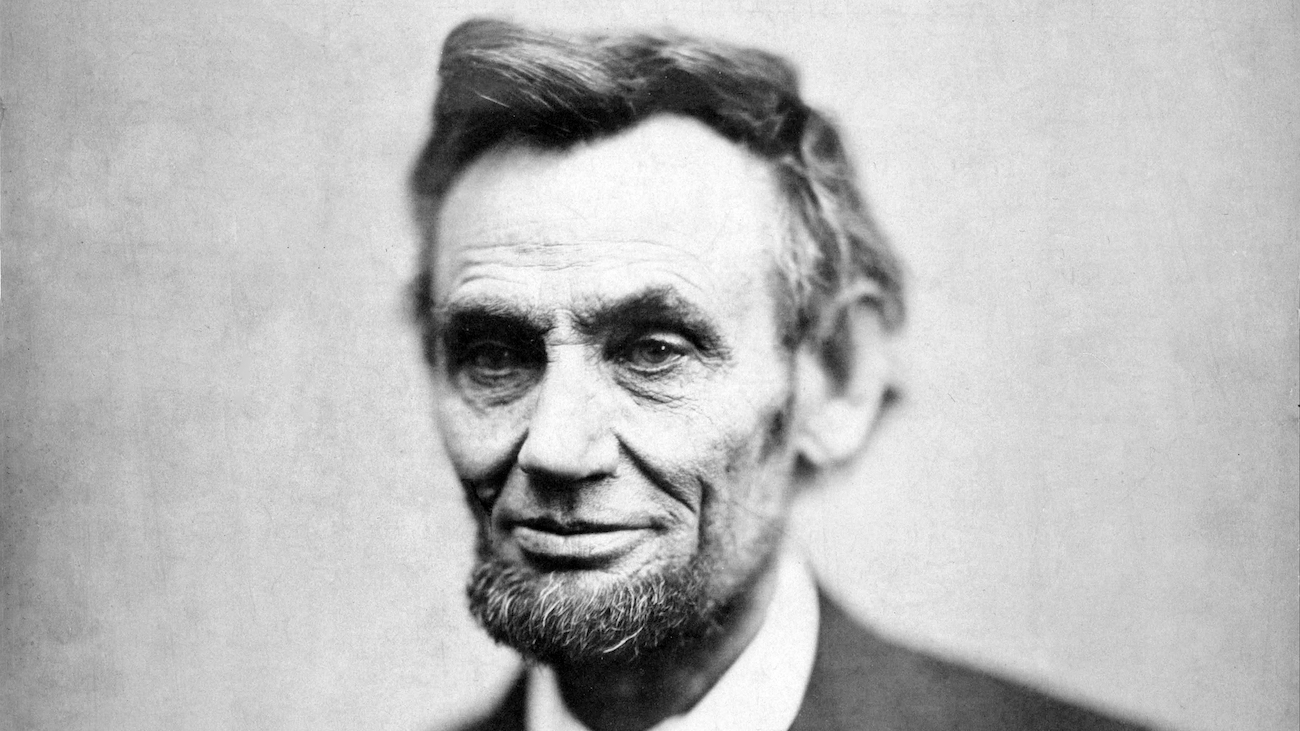

Miss Miner was born in 1815 in Brookfield, New York. Brought up in poverty herself, and sometimes suffering from illness, she still kept going to school. She expanded her education by reading all she could, and borrowing books from neighbors, rather like the young Abraham Lincoln. Although she didn’t pick up extra money by splitting rails like Lincoln, she did pick hops, using the money to buy more books.

In 1830, at age 15, she became a schoolteacher at Rochester, N.Y., followed by Providence, Rhode Island—-and then, sometime in 1849 or 1850, she took a job in Whitesville, Mississippi, teaching the daughter of a plantation owner. There she saw at first-hand the workings of the slave system.

She asked the planter if she could teach the slaves too, which drew the response, “Why don’t you go North and teach the _______ if you are so anxious to do it?” In 1851 she left for Washington to found a normal school for black schoolgirls there. She later wrote, “…I find no difference of native talent, where similar advantages are enjoyed, between Anglo-Saxons and Africo-Americans.”

Her friends advised against it, among them Frederick Douglass, who later wrote, “To me the proposition was reckless, almost to the point of madness. In my fancy I saw this fragile little woman harassed by the law, insulted on the street, a victim of slave-holding malice, and possibly beaten down by the mob.” Washington, after all, was a slave-holding town, where most of the authorities were pro-slavery.

Frail but brave, Miss Miner continued anyhow, using $100 given her by a Quaker friend, a Mrs. Ednah Thomas. Miner rented a few rooms, and began teaching on December 3, 1851. She soon had 40 students. Miner hoped they would become teachers themselves. The school was called The Colored Girls School.

As predicted, she was harassed and insulted, and also found it difficult to obtain lodging. Still, over the next two years, she went fund-raising, and got enough money to acquire three acres, with two small houses on the land. Among the donors was Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, who donated $1,000. Besides money, other people gave books, magazines, newspapers, and writing paper.

Tuition was $15 per year, the income providing the salaries for Miss Miner and her assistants, but there were some students there who could pay only part of that, or none at all. Often, Miss Miner had to turn away imploring parents, when the school simply had no more room.

Despite threats against the school, it was not actually attacked. Miss Miner believed this was due to the intervention of Mrs. Jane Pierce, wife of President Franklin Pierce, and the First Lady. Hearing that a riot was about to take place, Mrs. Pierce drove over to the school several times in her carriage, for a visit. The not-so-subtle message: Maybe the D.C. government wouldn’t do anything, but the federal government would.

Miss Miner kept teaching until her death in 1864 from a carriage accident. The school shut down, but was then taken up by Howard University in 1871. In 1876 the school trustees decided to re-organize it and become independent of Howard again.

They sold the original school land for $40,000, and built a new large building elsewhere, as a normal school again, named “The Institute for the Education of Colored Youth.” By June 1884, it had a graduation class of 82 women. Of those, 64 went on to teach in Washington schools.

One way or another the school has continued to the present day. Once again, Washington, D.C. has a large and varied history, for such a young city.

Sources:

Friend’s Review—–March 4, 1854, page 397; and March 25, 1886, page 529.

Liberator—-June 5, 1857, page 92.

National Era (D.C.) —April 30, 1857, page 70.

The Independent—May 11, 1876, page 8.

Friend’s Intelligencer—December 12, 1885, page 699.